.

This post compares the performance of high achievers from selected jurisdictions on the PISA 2012 creative problem solving test.

It draws principally on the material in the OECD Report ‘PISA 2012 Results: Creative Problem Solving’ published on 1 April 2014.

The sample of jurisdictions includes England, other English-speaking countries (Australia, Canada, Ireland and the USA) and those that typically top the PISA rankings (Finland, Hong Kong, South Korea, Shanghai, Singapore and Taiwan).

The sample of jurisdictions includes England, other English-speaking countries (Australia, Canada, Ireland and the USA) and those that typically top the PISA rankings (Finland, Hong Kong, South Korea, Shanghai, Singapore and Taiwan).

With the exception of New Zealand, which did not take part in the problem solving assessment, this is deliberately identical to the sample I selected for a parallel post reviewing comparable results in the PISA 2012 assessments of reading, mathematics and science: ‘PISA 2012: International Comparisons of High Achievers’ Performance’ (December 2013)

These eleven jurisdictions account for nine of the top twelve performers ranked by mean overall performance in the problem solving assessment. (The USA and Ireland lie outside the top twelve, while Japan, Macao and Estonia are the three jurisdictions that are in the top twelve but outside my sample.)

The post is divided into seven sections:

- Background to the problem solving assessment: How PISA defines problem solving competence; how it defines performance at each of the six levels of proficiency; how it defines high achievement; the nature of the assessment and who undertook it.

- Average performance, the performance of high achievers and the performance of low achievers (proficiency level 1) on the problem solving assessment. This comparison includes my own sample and all the other jurisdictions that score above the OECD average on the first of these measures.

- Gender and socio-economic differences amongst high achievers on the problem solving assessment in my sample of eleven jurisdictions.

- The relative strengths and weaknesses of jurisdictions in this sample on different aspects of the problem solving assessment. (This treatment is generic rather than specific to high achievers.)

- What proportion of high achievers on the problem-solving assessment in my sample of jurisdictions are also high achievers in reading, maths and science respectively.

- What proportion of students in my sample of jurisdictions achieves highly in one or more of the four PISA 2012 assessments – and against the ‘all-rounder’ measure, which is based on high achievement in all of reading, maths and science (but not problem solving).

- Implications for education policy makers seeking to improve problem solving performance in each of the sample jurisdictions.

.

Background to the Problem Solving Assessment

.

Definition of problem solving

PISA’s definition of problem-solving competence is:

‘…an individual’s capacity to engage in cognitive processing to understand and resolve problem situations where a method of solution is not immediately obvious. It includes the willingness to engage with such situations in order to achieve one’s potential as a constructive and reflective citizen.’

The commentary on this definition points out that:

- Problem solving requires identification of the problem(s) to be solved, planning and applying a solution, and monitoring and evaluating progress.

- A problem is ‘a situation in which the goal cannot be achieved by merely applying learned procedures’, so the problems encountered must be non-routine for 15 year-olds, although ‘knowledge of general strategies’ may be useful in solving them.

- Motivational and affective factors are also in play.

The Report is rather coy about the role of creativity in problem solving, and hence the justification for the inclusion of this term in its title.

Perhaps the nearest it gets to an exposition is when commenting on the implications of its findings:

‘In some countries and economies, such as Finland, Shanghai-China and Sweden, students master the skills needed to solve static, analytical problems similar to those that textbooks and exam sheets typically contain as well or better than 15-year-olds, on average, across OECD countries. But the same 15-year-olds are less successful when not all information that is needed to solve the problem is disclosed, and the information provided must be completed by interacting with the problem situation. A specific difficulty with items that require students to be open to novelty, tolerate doubt and uncertainty, and dare to use intuitions (“hunches and feelings”) to initiate a solution suggests that opportunities to develop and exercise these traits, which are related to curiosity, perseverance and creativity, need to be prioritised.’

.

Assessment framework

PISA’s framework for assessing problem solving competence is set out in the following diagram

In solving a particular problem it may not be necessary to apply all these steps, or to apply them in this order.

.

Proficiency levels

The proficiency scale was designed to have a mean score across OECD countries of 500. The six levels of proficiency applied in the assessment each have their own profile.

The lowest, level 1 proficiency is described thus:

‘At Level 1, students can explore a problem scenario only in a limited way, but tend to do so only when they have encountered very similar situations before. Based on their observations of familiar scenarios, these students are able only to partially describe the behaviour of a simple, everyday device. In general, students at Level 1 can solve straightforward problems provided there is a simple condition to be satisfied and there are only one or two steps to be performed to reach the goal. Level 1 students tend not to be able to plan ahead or set sub-goals.’

This level equates to a range of scores from 358 to 423. Across the OECD sample, 91.8% of participants are able to perform tasks at this level.

By comparison, level 5 proficiency is described in this manner:

‘At Level 5, students can systematically explore a complex problem scenario to gain an understanding of how relevant information is structured. When faced with unfamiliar, moderately complex devices, such as vending machines or home appliances, they respond quickly to feedback in order to control the device. In order to reach a solution, Level 5 problem solvers think ahead to find the best strategy that addresses all the given constraints. They can immediately adjust their plans or backtrack when they detect unexpected difficulties or when they make mistakes that take them off course.’

The associated range of scores is from 618 to 683 and 11.4% of all OECD students achieve at this level.

Finally, level 6 proficiency is described in this way:

‘At Level 6, students can develop complete, coherent mental models of diverse problem scenarios, enabling them to solve complex problems efficiently. They can explore a scenario in a highly strategic manner to understand all information pertaining to the problem. The information may be presented in different formats, requiring interpretation and integration of related parts. When confronted with very complex devices, such as home appliances that work in an unusual or unexpected manner, they quickly learn how to control the devices to achieve a goal in an optimal way. Level 6 problem solvers can set up general hypotheses about a system and thoroughly test them. They can follow a premise through to a logical conclusion or recognise when there is not enough information available to reach one. In order to reach a solution, these highly proficient problem solvers can create complex, flexible, multi-step plans that they continually monitor during execution. Where necessary, they modify their strategies, taking all constraints into account, both explicit and implicit.’

The range of level 6 scores is from 683 points upwards and 2.5% of all OECD participants score at this level.

PISA defines high achieving students as those securing proficiency level 5 or higher, so proficiency levels 5 and 6 together. The bulk of the analysis it supplies relates to this cohort, while relatively little attention is paid to the more exclusive group achieving proficiency level 6, even though almost 10% of students in Singapore reach this standard in problem solving.

.

The sample

Sixty-five jurisdictions took part in PISA 2012, including all 34 OECD countries and 31 partners. But only 44 jurisdictions took part in the problem solving assessment, including 28 OECD countries and 16 partners. As noted above, that included all my original sample of twelve jurisdictions, with the exception of New Zealand.

I could find no stated reason why New Zealand chose not to take part. Press reports initially suggested that England would do likewise, but it was subsequently reported that this decision had been reversed.

The assessment was computer-based and comprised 16 units divided into 42 items. The units were organised into four clusters, each designed to take 20 minutes to complete. Participants completed one or two clusters, depending on whether they were also undertaking computer-based assessments of reading and maths.

In each jurisdiction a random sample of those who took part in the paper-based maths assessment was selected to undertake the problem solving assessment. About 85,000 students took part in all. The unweighted sample sizes in my selected jurisdictions are set out in Table 1 below, together with the total population of 15 year-olds in each jurisdiction.

Table 1: Sample sizes undertaking PISA 2012 problem solving assessment in selected jurisdictions

.

| Country |

Unweighted Sample |

Total 15 year-olds |

| Australia |

5,612 |

291,976 |

| Canada |

4,601 |

417,873 |

| Finland |

3,531 |

62,523 |

| Hong Kong |

1,325 |

84,200 |

| Ireland |

1,190 |

59,296 |

| Shanghai |

1,203 |

108,056 |

| Singapore |

1,394 |

53,637 |

| South Korea |

1,336 |

687,104 |

| Taiwan |

1,484 |

328,356 |

| UK (England) |

1,458 |

738,066 |

| USA |

1,273 |

3,985,714 |

.

Those taking the assessment were aged between 15 years and three months and 16 years and two months at the time of the assessment. All were enrolled at school and had completed at least six years of formal schooling.

.

Average performance compared with the performance of high and low achievers

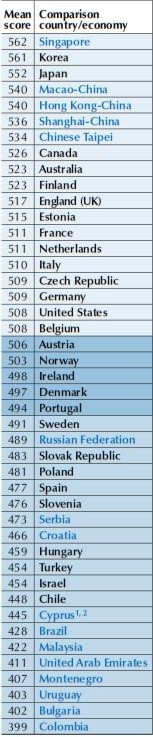

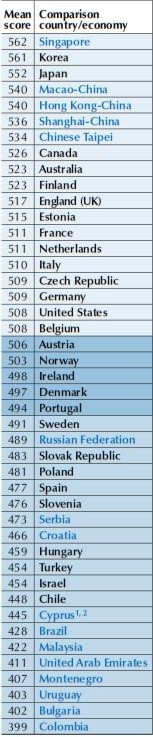

The overall table of mean scores on the problem solving assessment is shown below

.

.

There are some familiar names at the top of the table, especially Singapore and South Korea, the two countries that comfortably lead the rankings. Japan is some ten points behind in third place but it in turn has a lead of twelve points over a cluster of four other Asian competitors: Macao, Hong Kong, Shanghai and Taiwan.

A slightly different picture emerges if we compare average performance with the proportion of learners who achieve the bottom proficiency level and the top two proficiency levels. Table 2 below compares these groups.

This table includes all the jurisdictions that exceeded the OECD average score. I have marked out in bold the countries in my sample of eleven which includes Ireland, the only one of them that did not exceed the OECD average.

.

Table 2: PISA Problem Solving 2012: Comparing Average Performance with Performance at Key Proficiency Levels

| Jurisdiction |

Mean score |

Level 1 (%) |

Level 5 (%) |

Level 6 (%) |

Levels 5+6 (%) |

| Singapore |

562 |

6.0 |

19.7 |

9.6 |

29.3 |

| South Korea |

561 |

4.8 |

20.0 |

7.6 |

27.6 |

| Japan |

552 |

5.3 |

16.9 |

5.3 |

22.2 |

| Macao |

540 |

6.0 |

13.8 |

2.8 |

16.6 |

| Hong Kong |

540 |

7.1 |

14.2 |

5.1 |

19.3 |

| Shanghai |

536 |

7.5 |

14.1 |

4.1 |

18.2 |

| Taiwan |

534 |

8.2 |

14.6 |

3.8 |

18.4 |

| Canada |

526 |

9.6 |

12.4 |

5.1 |

17.5 |

| Australia |

523 |

10.5 |

12.3 |

4.4 |

16.7 |

| Finland |

523 |

9.9 |

11.4 |

3.6 |

15.0 |

| England (UK) |

517 |

10.8 |

10.9 |

3.3 |

14.2 |

| Estonia |

515 |

11.1 |

9.5 |

2.2 |

11.7 |

| France |

511 |

9.8 |

9.9 |

2.1 |

12.0 |

| Netherlands |

511 |

11.2 |

10.9 |

2.7 |

13.6 |

| Italy |

510 |

11.2 |

8.9 |

1.8 |

10.7 |

| Czech Republic |

509 |

11.9 |

9.5 |

2.4 |

11.9 |

| Germany |

509 |

11.8 |

10.1 |

2.7 |

12.8 |

| USA |

508 |

12.5 |

8.9 |

2.7 |

11.6 |

| Belgium |

508 |

11.6 |

11.4 |

3.0 |

14.4 |

| Austria |

506 |

11.9 |

9.0 |

2.0 |

11.0 |

| Norway |

503 |

13.2 |

9.7 |

3.4 |

13.1 |

| Ireland |

498 |

13.3 |

7.3 |

2.1 |

9.4 |

| OECD Ave. |

500 |

13.2 |

8.9 |

2.5 |

11.4 |

.

The jurisdictions at the top of the table also have a familiar profile, with a small ‘tail’ of low performance combined with high levels of performance at the top end.

Nine of the top ten have fewer than 10% of learners at proficiency level 1, though only South Korea pushes below 5%.

Five of the top ten have 5% or more of their learners at proficiency level 6, but only Singapore and South Korea have a higher percentage at level 6 than level 1 (with Japan managing the same percentage at both levels).

The top three performers – Singapore, South Korea and Japan – are the only three jurisdictions that have over 20% of their learners at proficiency levels 5 and 6 together.

South Korea slightly outscores Singapore at level 5 (20.0% against 19.7%). Japan is in third place, followed by Taiwan, Hong Kong and Shanghai.

But at level 6, Singapore has a clear lead, followed by South Korea, Japan, Hong Kong and Canada respectively.

England’s overall place in the table is relatively consistent on each of these measures, but the gaps between England and the top performers vary considerably.

The best have fewer than half England’s proportion of learners at proficiency level 1, almost twice as many learners at proficiency level 5 and more than twice as many at proficiency levels 5 and 6 together. But at proficiency level 6 they have almost three times as many learners as England.

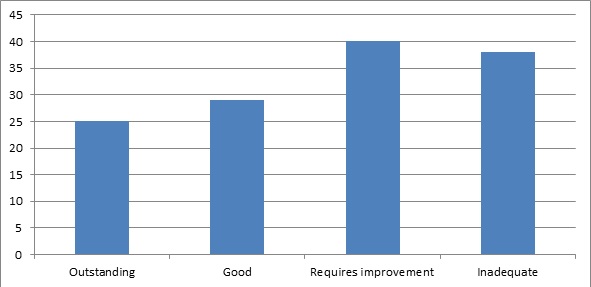

Chart 1 below compares performance on these four measures across my sample of eleven jurisdictions.

All but Ireland are comfortably below the OECD average for the percentage of learners at proficiency level 1. The USA and Ireland are atypical in having a bigger tail (proficiency level 1) than their cadres of high achievers (levels 5 and 6 together).

At level 5 all but Ireland and the USA are above the OECD average, but USA leapfrogs the OECD average at level 6.

There is a fairly strong correlation between the proportions of learners achieving the highest proficiency thresholds and average performance in each jurisdiction. However, Canada stands out by having an atypically high proportion of students at level 6.

.

Chart 1: PISA 2012 Problem-solving: Comparing performance at specified proficiency levels

.

PISA’s Report discusses the variation in problem-solving performance within different jurisdictions. However it does so without reference to the proficiency levels, so we do not know to what extent these findings apply equally to high achievers.

Amongst those above the OECD average, those with least variation are Macao, Japan, Estonia, Shanghai, Taiwan, Korea, Hong Kong, USA, Finland, Ireland, Austria, Singapore and the Czech Republic respectively.

Perhaps surprisingly, the degree of variation in Finland is identical to that in the USA and Ireland, while Estonia has less variation than many of the Asian jurisdictions. Singapore, while top of the performance table, is only just above the OECD average in terms of variation.

The countries below the OECD average on this measure – listed in order of increasing variation – include England, Australia and Canada, though all three are relatively close to the OECD average. So these three countries and Singapore are all relatively close together.

.

Gender and socio-economic differences amongst high achievers

.

Gender differences

On average across OECD jurisdictions, boys score seven points higher than girls on the problem solving assessment. There is also more variation amongst boys than girls.

Across the OECD participants, 3.1% of boys achieved proficiency level 6 but only 1.8% of girls did so. This imbalance was repeated at proficiency level 5, achieved by 10% of boys and 7.7% of girls.

The table and chart below show the variations within my sample of eleven countries. The performance of boys exceeds that of girls in all cases, except in Finland at proficiency level 5, and in that instance the gap in favour of girls is relatively small (0.4%).

.

Table 3: PISA Problem-solving: Gender variation at top proficiency levels

| Jurisdiction |

Level 5 (%) |

Level 6 (%) |

Levels 5+6 (%) |

| |

Boys |

Girls |

Diff |

Boys |

Girls |

Diff |

Boys |

Girls |

Diff |

| Singapore |

20.4 |

19.0 |

+1.4 |

12.0 |

7.1 |

+4.9 |

32.4 |

26.1 |

+6.3 |

| South Korea |

21.5 |

18.3 |

+3.2 |

9.4 |

5.5 |

+3.9 |

30.9 |

23.8 |

+7.1 |

| Hong Kong |

15.7 |

12.4 |

+3.3 |

6.1 |

3.9 |

+2.2 |

21.8 |

16.3 |

+5.5 |

| Shanghai |

17.0 |

11.4 |

+5.6 |

5.7 |

2.6 |

+3.1 |

22.7 |

14.0 |

+8.7 |

| Taiwan |

17.3 |

12.0 |

+5.3 |

5.0 |

2.5 |

+2.5 |

22.3 |

14.5 |

+7.8 |

| Canada |

13.1 |

11.8 |

+1.3 |

5.9 |

4.3 |

+1.6 |

19.0 |

16.1 |

+2.9 |

| Australia |

12.6 |

12.0 |

+0.6 |

5.1 |

3.7 |

+1.4 |

17.7 |

15.7 |

+2.0 |

| Finland |

11.2 |

11.6 |

-0.4 |

4.1 |

3.0 |

+1.1 |

15.3 |

14.6 |

+0.7 |

| England (UK) |

12.1 |

9.9 |

+2.2 |

3.6 |

3.0 |

+0.6 |

15.7 |

12.9 |

+2.8 |

| USA |

9.8 |

7.9 |

+1.9 |

3.2 |

2.3 |

+0.9 |

13.0 |

10.2 |

+2.8 |

| Ireland |

8.0 |

6.6 |

+1.4 |

3.0 |

1.1 |

+1.9 |

11.0 |

7.7 |

+3.3 |

| OECD Average |

10.0 |

7.7 |

+2.3 |

3.1 |

1.8 |

+1.3 |

13.1 |

9.5 |

+3.6 |

.

There is no consistent pattern in whether boys are more heavily over-represented at proficiency level 5 than proficiency level 6, or vice versa.

There is a bigger difference at level 6 than at level 5 in Singapore, South Korea, Canada, Australia, Finland and Ireland, but the reverse is true in the five remaining jurisdictions.

At level 5, boys are in the greatest ascendancy in Shanghai and Taiwan while, at level 6, this is true of Singapore and South Korea.

When proficiency levels 5 and 6 are combined, all five of the Asian tigers show a difference in favour of males of 5.5% or higher, significantly in advance of the six ‘Western’ countries in the sample and significantly ahead of the OECD average.

Amongst the six ‘Western’ representatives, boys have the biggest advantage at proficiency level 5 in England, while at level 6 boys in Ireland have the biggest advantage.

Within this group of jurisdictions, the gap between boys and girls at level 6 is comfortably the smallest in England. But, in terms of performance at proficiency levels 5 and 6 together, Finland is ahead.

.

Chart 2: PISA Problem-solving: Gender variation at top proficiency levels

.

.

The Report includes a generic analysis of gender differences in performance for boys and girls with similar levels of performance in English, maths and science.

It concludes that girls perform significantly above their expected level in both England and Australia (though the difference is only statistically significant in the latter).

The Report comments:

‘It is not clear whether one should expect there to be a gender gap in problem solving. On the one hand, the questions posed in the PISA problem-solving assessment were not grounded in content knowledge, so boys’ or girls’ advantage in having mastered a particular subject area should not have influenced results. On the other hand… performance in problem solving is more closely related to performance in mathematics than to performance in reading. One could therefore expect the gender difference in performance to be closer to that observed in mathematics – a modest advantage for boys, in most countries – than to that observed in reading – a large advantage for girls.’

.

Socio-economic differences

The Report considers variations in performance against PISA’s Index of Economic, Social and Cultural status (IESC), finding them weaker overall than for reading, maths and science.

It calculates that the overall percentage variation in performance attributable to these factors is about 10.6% (compared with 14.9% in maths, 14.0% in science and 13.2% in reading).

Amongst the eleven jurisdictions in my sample, the weakest correlations were found in Canada (4%), followed by Hong Kong (4.9%), South Korea (5.4%), Finland (6.5%), England (7.8%), Australia (8.5%), Taiwan (9.4%), the USA (10.1%) and Ireland (10.2%) in that order. All those jurisdictions had correlations below the OECD average.

Perhaps surprisingly, there were above average correlations in Shanghai (14.1%) and, to a lesser extent (and less surprisingly) in Singapore (11.1%).

The report suggests that students with parents working in semi-skilled and elementary occupations tend to perform above their expected level in problem-solving in Taiwan, England, Canada, the USA, Finland and Australia (in that order – with Australia closest to the OECD average).

The jurisdictions where these students tend to underperform their expected level are – in order of severity – Ireland, Shanghai, Singapore, Hong Kong and South Korea.

A parallel presentation on the Report provides some additional data about the performance in different countries of what the OECD calls ‘resilient’ students – those in the bottom quartile of the IESC but in the top quartile by perfromance, after accounting for socio-economic status.

It supplies the graph below, which shows all the Asian countries in my sample clustered at the top, but also with significant gaps between them. Canada is the highest-performing of the remainder in my sample, followed by Finland, Australia, England and the USA respectively. Ireland is some way below the OECD average.

.

.

Unfortunately, I can find no analysis of how performance varies according to socio-economic variables at each proficiency level. It would be useful to see which jurisdictions have the smallest ‘excellence gaps’ at levels 5 and 6 respectively.

.

How different jurisdictions perform on different aspects of problem-solving

The Report’s analysis of comparative strengths and weaknesses in different elements of problem-solving does not take account of variations at different proficiency levels

It explains that aspects of the assessment were found easier by students in different jurisdictions, employing a four-part distinction between:

‘Exploring and understanding. The objective is to build mental representations of each of the pieces of information presented in the problem. This involves:

- exploring the problem situation: observing it, interacting with it, searching for information and finding limitations or obstacles; and

- understanding given information and, in interactive problems, information discovered while interacting with the problem situation; and demonstrating understanding of relevant concepts.

Representing and formulating. The objective is to build a coherent mental representation of the problem situation (i.e. a situation model or a problem model). To do this, relevant information must be selected, mentally organised and integrated with relevant prior knowledge. This may involve:

- representing the problem by constructing tabular, graphic, symbolic or verbal representations, and shifting between representational formats; and

- formulating hypotheses by identifying the relevant factors in the problem and their inter-relationships; and organising and critically evaluating information.

Planning and executing. The objective is to use one’s knowledge about the problem situation to devise a plan and execute it. Tasks where “planning and executing” is the main cognitive demand do not require any substantial prior understanding or representation of the problem situation, either because the situation is straightforward or because these aspects were previously solved. “Planning and executing” includes:

- planning, which consists of goal setting, including clarifying the overall goal, and setting subgoals, where necessary; and devising a plan or strategy to reach the goal state, including the steps to be undertaken; and

- executing, which consists of carrying out a plan.

Monitoring and reflecting.The objective is to regulate the distinct processes involved in problem solving, and to critically evaluate the solution, the information provided with the problem, or the strategy adopted. This includes:

- monitoring progress towards the goal at each stage, including checking intermediate and final results, detecting unexpected events, and taking remedial action when required; and

- reflecting on solutions from different perspectives, critically evaluating assumptions and alternative solutions, identifying the need for additional information or clarification and communicating progress in a suitable manner.’

Amongst my sample of eleven jurisdictions:

- ‘Exploring and understanding’ items were found easier by students in Singapore, Hong Kong, South Korea, Australia, Taiwan and Finland.

- ‘Representing and formulating’ items were found easier in Taiwan, Shanghai, South Korea, Singapore, Hong Kong, Canada and Australia.

- ‘Planning and executing’ items were found easier in Finland only.

- ‘Monitoring and reflecting’ items were found easier in Ireland, Singapore, the USA and England.

The Report concludes:

‘This analysis shows that, in general, what differentiates high-performing systems, and particularly East Asian education systems, such as those in Hong Kong-China, Japan, Korea [South Korea], Macao-China, Shanghai -China, Singapore and Chinese Taipei [Taiwan], from lower-performing ones, is their students’ high level of proficiency on “exploring and understanding” and “representing and formulating” tasks.’

It also distinguishes those jurisdictions that perform best on interactive problems, requiring students to discover some of the information required to solve the problem, rather than being presented with all the necessary information. This seems to be the nearest equivalent to a measure of creativity in problem solving

Comparative strengths and weaknesses in respect of interactive tasks are captured in the following diagram.

.

.

One can see that several of my sample – Ireland, the USA, Canada, Australia, South Korea and Singapore – are placed in the top right-hand quarter of the diagram, indicating stronger than expected performance on both interactive and knowledge acquisition tasks.

England is stronger than expected on the former but not on the latter.

Jurisdictions that are weaker than inspected on interactive tasks only include Hong Kong, Taiwan and Shanghai, while Finland is weaker than expected on both.

We have no information about whether these distinctions were maintained at different proficiency levels.

.

Comparing jurisdictions’ performance at higher proficiency levels

Table 4 and Charts 3 and 4 below show variations in the performance of countries in my sample across the four different assessments at level 6, the highest proficiency level.

The charts in particular emphasise how far ahead the Asian Tigers are in maths at this level, compared with the cross-jurisdictional variation in the other three assessments.

In all five cases, each ‘Asian Tiger’s’ level 6 performance in maths also vastly exceeds its level 6 performance in the other three assessments. The proportion of students achieving level 6 proficiency in problem solving lags far behind, even though there is a fairly strong correlation between these two assessments (see below).

In contrast, all the ‘Western’ jurisdictions in the sample – with the sole exception of Ireland – achieve a higher percentage at proficiency level 6 in problem solving than they do in maths, although the difference is always less than a full percentage point. (Even in Ireland the difference is only 0.1 of a percentage point in favour of maths.)

Shanghai is the only jurisdiction in the sample which has more students achieving proficiency level 6 in science than in problem solving. It also has the narrowest gap between level 6 performance in problem solving and in reading.

Meanwhile, England, the USA, Finland and Australia all have broadly similar profiles across the four assessments, with the largest percentage of level 6 performers in problem solving, followed by maths, science and reading respectively.

The proximity of the lines marking level 6 performance in reading and science is also particularly evident in the second chart below.

.

Table 4: Percentage achieving proficiency Level 6 in each domain

| |

PS L6 |

Ma L6 |

Sci L6 |

Re L6 |

| Singapore |

9.6 |

19.0 |

5.8 |

5.0 |

| South Korea |

7.6 |

12.1 |

1.1 |

1.6 |

| Hong Kong |

5.1 |

12.3 |

1.8 |

1.9 |

| Shanghai |

4.1 |

30.8 |

4.2 |

3.8 |

| Taiwan |

3.8 |

18.0 |

0.6 |

1.4 |

| Canada |

5.1 |

4.3 |

1.8 |

2.1 |

| Australia |

4.4 |

4.3 |

2.6 |

1.9 |

| Finland |

3.6 |

3.5 |

3.2 |

2.2 |

| England (UK) |

3.3 |

3.1 |

1.9 |

1.3 |

| USA |

2.7 |

2.2 |

1.1 |

1.0 |

| Ireland |

2.1 |

2.2 |

1.5 |

1.3 |

| OECD Average |

2.5 |

3.3 |

1.2 |

1.1 |

.

Charts 3 and 4: Percentage achieving proficiency level 6 in each domain

.

.

The pattern is materially different at proficiency levels 5 and above, as the table and chart below illustrate. These also include the proportion of all-rounders, who achieved proficiency level 5 or above in each of maths, science and reading (but not in problem-solving).

The lead enjoyed by the ‘Asian Tigers’ in maths is somewhat less pronounced. The gap between performance within these jurisdictions on the different assessments also tends to be less marked, although maths accounts for comfortably the largest proportion of level 5+ performance in all five cases.

Conversely, level 5+ performance on the different assessments is typically much closer in the ‘Western’ countries. Problem solving leads the way in Australia, Canada, England and the USA, but in Finland science is in the ascendant and reading is strongest in Ireland.

Some jurisdictions have a far ‘spikier’ profile than others. Ireland is closest to achieving equilibrium across all four assessments. Australia and England share very similar profiles, though Australia outscores England in each assessment.

The second chart in particular shows how Shanghai’s ‘spike’ applies in all the other three assessments but not in problem solving.

.

Table 5: Percentage achieving Proficiency level 5 and above in each domain

| |

PS L5+ |

Ma L5+ |

Sci L5+ |

Re L5+ |

Ma + Sci + Re L5+ |

| Singapore |

29.3 |

40.0 |

22.7 |

21.2 |

16.4 |

| South Korea |

27.6 |

30.9 |

11.7 |

14.2 |

8.1 |

| Hong Kong |

19.3 |

33.4 |

16.7 |

16.8 |

10.9 |

| Shanghai |

18.2 |

55.4 |

27.2 |

25.1 |

19.6 |

| Taiwan |

18.4 |

37.2 |

8.4 |

11.8 |

6.1 |

| Canada |

17.5 |

16.4 |

11.3 |

12.9 |

6.5 |

| Australia |

16.7 |

14.8 |

13.5 |

11.7 |

7.6 |

| Finland |

15.0 |

15.2 |

17.1 |

13.5 |

7.4 |

| England (UK) |

14.2 |

12.4 |

11.7 |

9.1 |

5.7* all UK |

| USA |

11.6 |

9.0 |

7.4 |

7.9 |

4.7 |

| Ireland |

9.4 |

10.7 |

10.8 |

11.4 |

5.7 |

| OECD Average |

11.4 |

12.6 |

8.4 |

8.4 |

4.4 |

.

Charts 5 and 6: Percentage Achieving Proficiency Level 5 and above in each domain

.

.

How high-achieving problem solvers perform in other assessments

.

Correlations between performance in different assessments

The Report provides an analysis of the proportion of students achieving proficiency levels 5 and 6 on problem solving who also achieved that outcome on one of the other three assessments: reading, maths and science.

It argues that problem solving is a distinct and separate domain. However:

‘On average, about 68% of the problem-solving score reflects skills that are also measured in one of the three regular assessment domains. The remaining 32% reflects skills that are uniquely captured by the assessment of problem solving. Of the 68% of variation that problem-solving performance shares with other domains, the overwhelming part is shared with all three regular assessment domains (62% of the total variation); about 5% is uniquely shared between problem solving and mathematics only; and about 1% of the variation in problem solving performance hinges on skills that are specifically measured in the assessments of reading or science.’

It discusses the correlation between these different assessments:

‘A key distinction between the PISA 2012 assessment of problem solving and the regular assessments of mathematics, reading and science is that the problem-solving assessment does not measure domain-specific knowledge; rather, it focuses as much as possible on the cognitive processes fundamental to problem solving. However, these processes can also be used and taught in the other subjects assessed. For this reason, problem-solving tasks are also included among the test units for mathematics, reading and science, where their solution requires expert knowledge specific to these domains, in addition to general problem-solving skills.

It is therefore expected that student performance in problem solving is positively correlated with student performance in mathematics, reading and science. This correlation hinges mostly on generic skills, and should thus be about the same magnitude as between any two regular assessment subjects.’

These overall correlations are set out in the table below, which shows that maths has a higher correlation with problem solving than either science or reading, but that this correlation is lower than those between the three subject-related assessments.

The correlation between maths and science (0.90) is comfortably the strongest (despite the relationship between reading and science at the top end of the distribution noted above).

.

.

Correlations are broadly similar across jurisdictions, but the Report notes that the association is comparatively weak in some of these, including Hong Kong. Students here are more likely to perform poorly on problem solving and well on other assessments, or vice versa.

There is also broad consistency at different performance levels, but the Report identifies those jurisdictions where students with the same level of performance exceed expectations in relation to problem-solving performance. These include South Korea, the USA, England, Australia, Singapore and – to a lesser extent – Canada.

Those with lower than expected performance include Shanghai, Ireland, Hong Kong, Taiwan and Finland.

The Report notes:

‘In Shanghai-China, 86% of students perform below the expected level in problem solving, given their performance in mathematics, reading and science. Students in these countries/economies struggle to use all the skills that they demonstrate in the other domains when asked to perform problem-solving tasks.’

However, there is variation according to students’ maths proficiency:

- Jurisdictions whose high scores on problem solving are mainly attributable to strong performers in maths include Australia, England and the USA.

- Jurisdictions whose high scores on problem solving are more attributable to weaker performers in maths include Ireland.

- Jurisdictions whose lower scores in problem solving are more attributable to weakness among strong performers in maths include Korea.

- Jurisdictions whose lower scores in problem solving are more attributable to weakness among weak performers in maths include Hong Kong and Taiwan.

- Jurisdictions whose weakness in problem solving is fairly consistent regardless of performance in maths include Shanghai and Singapore.

The Report adds:

‘In Italy, Japan and Korea, the good performance in problem solving is, to a large extent, due to the fact that lower performing students score beyond expectations in the problem-solving assessment….This may indicate that some of these students perform below their potential in mathematics; it may also indicate, more positively, that students at the bottom of the class who struggle with some subjects in school are remarkably resilient when it comes to confronting real-life challenges in non-curricular contexts…

In contrast, in Australia, England (United Kingdom) and the United States, the best students in mathematics also have excellent problem-solving skills. These countries’ good performance in problem solving is mainly due to strong performers in mathematics. This may suggest that in these countries, high performers in mathematics have access to – and take advantage of – the kinds of learning opportunities that are also useful for improving their problem-solving skills.’

.

What proportion of high performers in problem solving are also high performers in one of the other assessments?

The percentages of high achieving students (proficiency level 5 and above) in my sample of eleven jurisdictions who perform equally highly in each of the three domain-specific assessments are shown in Table 6 and Chart 7 below.

These show that Shanghai leads the way in each case, with 98.0% of all students who achieve proficiency level 5+ in problem solving also achieving the same outcome in maths. For science and reading the comparable figures are 75.1% and 71.7% respectively.

Taiwan is the nearest competitor in respect of problem solving plus maths, Finland in the case of problem solving plus science and Ireland in the case of problem solving plus reading.

South Korea, Taiwan and Canada are atypical of the rest in recording a higher proportion of problem solving plus reading at this level than problem solving plus science.

Singapore, Shanghai and Ireland are the only three jurisdictions that score above 50% on all three of these combinations. However, the only jurisdictions that exceed the OECD averages in all three cases are Singapore, Hong Kong, Shanghai and Finland.

.

Table 6: PISA problem-solving: Percentage of students achieving proficiency level 5+ in domain-specific assessments

| |

PS + Ma |

PS + Sci |

PS + Re |

| Singapore |

84.1 |

57.0 |

50.2 |

| South Korea |

73.5 |

34.1 |

40.3 |

| Hong Kong |

79.8 |

49.4 |

48.9 |

| Shanghai |

98.0 |

75.1 |

71.7 |

| Taiwan |

93.0 |

35.3 |

43.7 |

| Canada |

57.7 |

43.9 |

44.5 |

| Australia |

61.3 |

54.9 |

47.1 |

| Finland |

66.1 |

65.4 |

49.5 |

| England (UK) |

59.0 |

52.8 |

41.7 |

| USA |

54.6 |

46.9 |

45.1 |

| Ireland |

59.0 |

57.2 |

52.0 |

| OECD Average |

63.5 |

45.7 |

41.0 |

.

Chart 7: PISA Problem-solving: Percentage of students achieving proficiency level 5+ in domain-specific assessments

.

.

What proportion of students achieve highly in one or more assessments?

Table 7 and Chart 8 below show how many students in each of my sample achieved proficiency level 5 or higher in problem-solving only, in problem solving and one or more assessments, in one or more assessments but not problem solving and in at least one assessment (ie the total of the three preceding columns).

I have also repeated in the final column the percentage achieving this proficiency level in each of maths, science and reading. (PISA has not released information about the proportion of students who achieved this feat across all four assessments.)

These reveal that the percentages of students who achieve proficiency level 5+ only in problem solving are very small, ranging from 0.3% in Shanghai to 6.7% in South Korea.

Conversely, the percentages of students achieving proficiency level 5+ in any one of the other assessments but not in problem solving are typically significantly higher, ranging from 4.5% in the USA to 38.1% in Shanghai.

There is quite a bit of variation in terms of whether jurisdictions score more highly on ‘problem solving and at least one other’ (second column) and ‘at least one other excluding problem solving (third column).

More importantly, the fourth column shows that the jurisdiction with the most students achieving proficiency level 5 or higher in at least one assessment is clearly Shanghai, followed by Singapore, Hong Kong, South Korea and Taiwan in that order.

The proportion of students achieving this outcome in Shanghai is close to three times the OECD average, comfortably more than twice the rate achieved in any of the ‘Western’ countries and three times the rate achieved in the USA.

The same is true of the proportion of students achieving this level in the three domain-specific assessments.

On this measure, South Korea and Taiwan fall significantly behind their Asian competitors, and the latter is overtaken by Australia, Finland and Canada.

.

Table 7: Percentage achieving proficiency level 5+ in different combinations of PISA assessments

| |

PS only% |

PS + 1 or more% |

1+ butNot PS% |

L5+ in at least one % |

L5+ in Ma + Sci + Re % |

| Singapore |

4.3 |

25.0 |

16.5 |

45.8 |

16.4 |

| South Korea |

6.7 |

20.9 |

11.3 |

38.9 |

8.1 |

| Hong Kong |

3.4 |

15.9 |

20.5 |

39.8 |

10.9 |

| Shanghai |

0.3 |

17.9 |

38.1 |

56.3 |

19.6 |

| Taiwan |

1.2 |

17.1 |

20.4 |

38.7 |

6.1 |

| Canada |

5.5 |

12.0 |

9.9 |

27.4 |

6.5 |

| Australia |

4.7 |

12.0 |

7.7 |

24.4 |

7.6 |

| Finland |

3.0 |

12.0 |

11.9 |

26.9 |

7.4 |

| England (UK) |

4.4 |

9.8 |

6.8 |

21.0 |

5.7* all UK |

| USA |

4.1 |

7.5 |

4.5 |

16.1 |

4.7 |

| Ireland |

2.6 |

6.8 |

10.1 |

19.5 |

5.7 |

| OECD Average |

3.1 |

8.2 |

8.5 |

19.8 |

4.4 |

.

Chart 8: Percentage achieving proficiency level 5+ in different combinations of PISA assessments

.

.

The Report comments:

‘The proportion of students who reach the highest levels of proficiency in at least one domain (problem solving, mathematics, reading or science) can be considered a measure of the breadth of a country’s/economy’s pool of top performers. By this measure, the largest pool of top performers is found in Shanghai-China, where more than half of all students (56%) perform at the highest levels in at least one domain, followed by Singapore (46%), Hong Kong-China (40%), Korea and Chinese Taipei (39%)…Only one OECD country, Korea, is found among the five countries/economies with the largest proportion of top performers. On average across OECD countries, 20% of students are top performers in at least one assessment domain.

The proportion of students performing at the top in problem solving and in either mathematics, reading or science, too can be considered a measure of the depth of this pool. These are top performers who combine the mastery of a specific domain of knowledge with the ability to apply their unique skills flexibly, in a variety of contexts. By this measure, the deepest pools of top performers can be found in Singapore (25% of students), Korea (21%), Shanghai-China (18%) and Chinese Taipei (17%). On average across OECD countries, only 8% of students are top performers in both a core subject and in problem solving.’

There is no explanation of why proficiency level 5 should be equated by PISA with the breadth of a jurisdiction’s ‘pool of top performers’. The distinction between proficiency levels 5 and 6 in this respect requires further discussion.

In addition to updated ‘all-rounder’ data showing what proportion of students achieved this outcome across all four assessments, it would be really interesting to see the proportion of students achieving at proficiency level 6 across different combinations of these four assessments – and to see what proportion of students achieving that outcome in different jurisdictions are direct beneficiaries of targeted support, such as a gifted education programme.

.

In the light of this analysis, what are jurisdictions’ priorities for improving problem solving performance?

Leaving aside strengths and weaknesses in different elements of problem solving discussed above, this analysis suggests that the eleven jurisdictions in my sample should address the following priorities:

Singapore has a clear lead at proficiency level 6, but falls behind South Korea at level 5 (though Singapore re-establishes its ascendancy when levels 5 and 6 are considered together). It also has more level 1 performers than South Korea. It should perhaps focus on reducing the size of this tail and pushing through more of its mid-range performers to level 5. There is a pronounced imbalance in favour of boys at level 6, so enabling more girls to achieve the highest level of performance is a clear priority. There may also be a case for prioritising the children of semi-skilled workers.

South Korea needs to focus on getting a larger proportion of its level 5 performers to level 6. This effort should be focused disproportionately on girls, who are significantly under-represented at both levels 5 and 6. South Korea has a very small tail to worry about – and may even be getting close to minimising this. It needs to concentrate on improving the problem solving skills of its stronger performers in maths.

Hong Kong has a slightly bigger tail than Singapore’s but is significantly behind at both proficiency levels 5 and 6. In the case of level 6 it is equalled by Canada. Hong Kong needs to focus simultaneously on reducing the tail and lifting performance across the top end, where girls and weaker performers in maths are a clear priority.

Shanghai has a similar profile to Hong Kong’s in all respects, though with somewhat fewer level 6 performers. It also needs to focus effort simultaneously at the top and the bottom of the distribution. Amongst this sample, Shanghai has the worst under-representation of girls at level 5 and levels 5 and 6 together, so addressing that imbalance is an obvious priority. It also demonstrated the largest variation in performance against PISA’s IESC index, which suggests that it should target young people from disadvantaged backgrounds, as well as the children of semi-skilled workers.

Taiwan is rather similar to Hong Kong and Shanghai, but its tail is slightly bigger and its level 6 cadre slightly smaller, while it does somewhat better at level 5. It may need to focus more at the very bottom, but also at the very top. Taiwan also has a problem with high-performing girls, second only to Shanghai as far as level 5 and levels 5 and 6 together are concerned. However, like Shanghai, it does comparatively better than the other ‘Asian Tigers’ in terms of girls at level 6. It also needs to consider the problem solving performance of its weaker performers in maths.

Canada is the closest western competitor to the ‘Asian Tigers’ in terms of the proportions of students at levels 1 and 5 – and it already outscores Shanghai and Taiwan at level 6. It needs to continue cutting down the tail without compromising achievement at the top end. Canada also has small but significant gender imbalances in favour of boys at the top end.

Australia by comparison is significantly worse than Canada at level 1, broadly comparable at level 5 and somewhat worse at level 6. It too needs to improve scores at the very bottom and the very top. Australia’s gender imbalance is more pronounced at level 6 than level 5.

Finland has the same mean score as Australia’s but a smaller tail (though not quite as small as Canada’s). It needs to improve across the piece but might benefit from concentrating rather more heavily at the top end. Finland has a slight gender imbalance in favour of girls at level 5, but boys are more in the ascendancy at level 6 than in either England or the USA. As in Australia, this latter point needs addressing.

England has a profile similar to Australia’s, but less effective at all three selected proficiency levels. It is further behind at the top than at the bottom of the distribution, but needs to work hard at both ends to catch up the strongest western performers and maintain its advantage over the USA and Ireland. Gender imbalances are small but nonetheless significant.

USA has a comparatively long tail of low achievement at proficiency level 1 and, with the exception of Ireland, the fewest high achievers. This profile is very close to the OECD average. As in England, the relatively small size of gender imbalances in favour of boys does not mean that these can be ignored.

Ireland has the longest tail of low achievement and the smallest proportion of students at proficiency levels 5, 6 and 5 and 6 combined. It needs to raise the bar at both ends of the achievement distribution. Ireland has a larger preponderance of boys at level 6 than its Western competitors and this needs addressing. The limited socio-economic evidence suggests that Ireland should also be targeting the offspring of parents with semi-skilled and elementary occupations.

So there is further scope for improvement in all eleven jurisdictions. Meanwhile the OECD could usefully provide a more in-depth analysis of high achievers on its assessments that features:

- Proficiency level 6 performance across the board.

- Socio-economic disparities in performance at proficiency levels 5 and 6.

- ‘All-rounder’ achievement at these levels across all four assessments and

- Correlations between success at these levels and specific educational provision for high achievers including gifted education programmes.

.

GP

April 2014

As I see it, there are three sets of issues with the ‘G’ word:

As I see it, there are three sets of issues with the ‘G’ word:

I shall not repeat here previous coverage of how Ofsted’s emphasis on the most able has been framed. Interested readers may wish to refer to previous posts for details:

I shall not repeat here previous coverage of how Ofsted’s emphasis on the most able has been framed. Interested readers may wish to refer to previous posts for details: