.

This post provides a close analysis of Ofsted’s Report: ‘The most able students: Are they doing as well as they should in our non-selective secondary schools?’ (June 2013)

.

,

summer of love 1967 by 0 fairy 0

This is the second post in a short series, predicated on the assumption that we are currently enjoying a domestic ‘summer of love’ for gifted education.

According to this conceit, the ‘summer of love’ is built around three official publications, all of them linked in some way with the education of gifted learners, and various associated developments.

Part One in the series introduced the three documents:

- An Ofsted Survey of how schools educate their most able pupils (still unpublished at that point); and

- A planned ‘Investigation of school and college level strategies to raise the aspirations of high-achieving disadvantaged pupils to pursue higher education’, this report programmed for publication in September 2013.

It provided a full analysis of the KS2 L6 Investigation and drew on the contractual specification for the Investigation of aspiration-raising strategies to set out what we know about its likely content and coverage.

It also explored the pre-publicity surrounding Ofsted’s Survey, which has been discussed exclusively by HMCI Wilshaw in the media. (There was no official announcement on Ofsted’s own website, though it did at least feature in their schedule of forthcoming publications.)

Part One also introduced a benchmark for the ‘The most able students’, in the shape of a review of Ofsted’s last foray into this territory – a December 2009 Survey called ‘Gifted and talented pupils in schools’.

I will try my best not to repeat too much material from Part One in this second Episode so, if you feel a little at sea without this background detail, I strongly recommend that you start with the middle section of that first post before reading this one.

I will also refer you, at least once, to various earlier posts of mine, including three I wrote on the day ‘The most able students’ was published:

- My Twitter Feed – A reproduction of the real time Tweets I published immediately the Report was made available online, summarising its key points and recommendations and conveying my initial reactions and those of several influential commentators and respondents. (If you don’t like long posts, go there for the potted version!);

Part Two is dedicated almost exclusively to analysis of ‘The most able students’ and the reaction to its publication to date.

It runs a fine tooth comb over the content of the Report, comparing its findings with those set out in Ofsted’s 2009 publication and offering some judgement as to whether it possesses the ‘landmark’ qualities boasted of it by HMCI in media interviews and/or whether it justifies the criticism heaped on it in some quarters.

It also matches Ofsted’s findings against the Institutional Quality Standards (IQS) for Gifted Education – the planning and improvement tool last refreshed in 2010 – to explore what that reveals about the coverage of each document.

For part of my argument is that, if schools are to address the issues exposed by Ofsted, they will need help and support to do so – not only a collaborative mechanism such as that proposed in ‘Driving Gifted Education Forward – but also some succinct, practical guidance that builds on the experience developed during the lifetime of the late National Gifted and Talented Programme.

For – if you’d like a single succinct take-away from this analysis – I firmly believe that it is now timely for the IQS to be reviewed and updated to better reflect current policy and the new evidence base created in part by Ofsted and the other two publications I am ‘celebrating’ as part of the Summer of Love.

Oh, and if you want to find out more about my ‘big picture’ vision, may I refer you finally to the Gifted Phoenix Manifesto for Gifted Education.

But now it’s high time I began to engage you directly with what has proved to be a rather controversial text.

.

Ofsted’s Definition of ‘Most Able’

The first thing to point out is that Ofsted’s Report is focused very broadly in one sense, but rather narrowly in another.

The logic-defying definition of ‘most able students’ Ofsted adopts – for the survey that informs the Report – is tucked away in a footnote divided between the bottom of pages 6 and 7 of the Report.

This says:

‘For the purpose of this survey ‘most able’ is defined as the brightest students starting secondary school in Year 7 attaining Level 5 or above, or having the potential to attain Level 5 and above, in English (reading and writing) and/or mathematics at the end of Key Stage 2. Some pupils who are new to the country and are learning English as an additional language, for example, might not have attained Level 5 or beyond at the end of Key Stage 2 but have the potential to achieve it.’

It is hard to reconcile this definition with the emphasis in the title of the Report on ‘the most able students’, which suggests a much narrower population at one extreme of an ability distribution (not an attainment distribution, although most of the Report is actually about high attaining students, something quite different).

In fact, Ofsted’s sample includes:

- All pupils achieving Level 5 and above in English – 38% of all pupils taking end KS2 tests in 2012 achieved this.

- All pupils achieving Level 5 and above in maths – 39% of all pupils achieved this in 2012.

- We also know that 27% of pupils achieved Level 5 or above in both English and maths in 2012. This enables us to deduce that approximately 11% of pupils managed Level 5 only in English and approximately 12% only in maths.

- So adding these three together we get 27% + 11% + 12% = 50%. In other words, we have already included exactly half of the entire pupil population and have so far counted only ‘high attaining’ pupils.

- But we also need to include a further proportion of pupils who ‘have the potential’ to achieve Level 5 in one or other of these subject but do not do so. This sub-population is unquantifiable, since Ofsted gives only the example of EAL pupils, rather than the full range of qualifying circumstances it has included. A range of different special needs might also cause a learner to be categorised thus. So might a particularly disadvantaged background (although that rather cuts across other messages within the Report). In practice, individual learners are typically affected by the complex interaction of a whole range of different factors, including gender, ethnic and socio-economic background, special needs, month of birth – and so on. Ofsted fails to explain which factors it has decided are within scope and which outside, or to provide any number or percentage for this group that we can tack on to the 50% already deemed high attainers.

Some might regard this lack of precision as unwarranted in a publication by our national Inspectorate, finding reason therein to ignore the important findings that Ofsted presents later in the Report. That would be unfortunate.

Not only is Ofsted’s definition very broad, it is also idiosyncratic, even in Government terms, because it is not the same as the slightly less generous version in the Secondary School Performance Tables, which is based on achievement of Level 5 in Key Stage 2 tests of English, maths and science.

So, according to this metric, Ofsted is concerned with the majority of pupils in our secondary schools – several million in fact.

But ‘The Most Able Students’ is focused exclusively on the segment of this population that attends non-selective 11-16 and 11-18 state schools.

We are told that only 160,000 students from a total of 3.235m in state-funded secondary schools attend selective institutions.

Another footnote adds that, in 2012, of 116,000 students meeting Ofsted’s ‘high attainers’ definition in state-funded schools who took GCSEs in English and maths, around 100,000 attended non-selective schools, compared with 16,000 in selective schools (so some 86%).

This imbalance is used to justify the exclusion of selective schools from the evidence base, even though some further direct comparison of the two sectors might have been instructive – possibly even supportive of the claim that there is a particular problem in comprehensive schools that is not found in selective institutions. Instead, we are asked to take this claim largely on trust.

.

Exeter1 by Gifted Phoenix

.

The Data-Driven Headlines

The Report includes several snippets of data-based evidence to illustrate its argument, most of which relate to subsets of the population it has rather loosely defined, rather than that population as a whole. This creates a problematic disconnect between the definition and the data.

One can group the data into three categories: material relating to progression between Key Stages 2 and 4, material relating to achievement of AAB+ grades at A level in the so-called ‘facilitating subjects’ and material drawn from international comparisons studies. The former predominates.

.

Data About Progression from KS2 to KS4

Ofsted does not explain up front the current expectation that pupils should make at least three full levels of progress between the end of Key Stage 2 and the end of Key Stage 4, or explore the fact that this assumption must disappear when National Curriculum levels go in 2016.

The conversion tables say that pupils achieving Level 5 at the end of Key Stage 2 should manage at least a Grade B at GCSE. Incidentally – and rather confusingly – that also includes pupils who are successful in the new Level 6 tests.

Hence the expectation does not apply to some of the very highest attainers who, rather than facing extra challenge, need only make two levels of progress in (what is typically) five years of schooling.

I have argued consistently that three levels of progress is insufficiently challenging for many high attainers. Ofsted makes that assumption too – even celebrates schools that push beyond it – but fails to challenge the source or substance of that advice.

We are supplied with the following pieces of data, all relating to 2012:

- 65% of ‘high attainers’ in non-selective secondary schools – not according to Ofsted’s definition above, but the narrower one of those achieving Key Stage 2 Level 5 in both English and maths – did not achieve GCSEs at A/A* in both those subjects. (So this is equivalent to 4 or 5 levels of progress in the two subjects combined.) This group includes over 65,000 students (see pages 4, 6, 8, 12).

- Within the same population, 27% of students did not achieve GCSEs at B or above in both English and maths. (So this is the expected 3+ levels of progress.) This accounts for just over 27,000 students.) (see pages 4, 6 and 12).

- On the basis of this measure, 42% of FSM-eligible students did not achieve GCSEs at B or above in both English and maths, whereas the comparable figure for non-FSM students was 25%, giving a gap between FSM and non-FSM (rather than between FSM and all students) of 17%. We are not told what the gap was at A*/A, or for the ‘survey population’ as a whole (page 14)

- Of those who achieved Level 5 in English (only) at Key Stage 2, 62% of those attending non-selective state schools did not achieve an A* or A Grade at GCSE (so making 4 or 5 levels of progress) and 25% did not achieve a GCSE B grade or higher (so making 3+ levels of progress) (page 12)

- Of those who achieved Level 5 in maths (only) at Key Stage 2, 53% did not achieve A*/A at GCSE (4 or 5 levels of progress) and 22% did not achieve B or higher (3+ levels of progress) (page 12)

- We are also given the differentials between boys and girls on several of these measures, but not the percentages for each gender. In English, for A*/A and for B and above, the gap is 11% in favour of girls. In maths, the gap is 6% in favour of girls at A*/A and 5% at B and above. In English and maths combined, the gap is 10% in favour of girls for A*/A and B and above alike (page 15).

- As for ethnic background, we learn that non-White British students outperformed White British students by 2% in maths and 1% in English and maths together, but the two groups performed equally in English at Grades B and above. The comparable data for Grades A*/A show non-White British outperforming White British by 3% in maths and again 1% in English and maths together, while the two groups again performed equally in English (page 16)

What can we deduce from this? Well, not to labour the obvious, but what is the point of setting out a definition, however exaggeratedly inclusive, only to move to a different definition in the data analysis?

Why bother to spell out a definition based on achievement in English or maths, only to rely so heavily on data relating to achievement in English and maths?

There are also no comparators. We cannot see how the proportion of high attainers making expected progress compares with the proportion of middle and low attainers doing so, so there is no way of knowing whether there is a particular problem at the upper end of the spectrum. We can’t see the comparable pattern in selective schools either.

There is no information about the trend over time – whether the underperformance of high attainers is improving, static or deteriorating compared with previous years – and how that pattern differs from the trend for middle and low attainers.

The same applies to the information about the FSM gap, which is confined solely to English and maths, and solely to Grade B and above, so we can’t see how their performance compares between the two subjects and for the top A*/A grades, even though that data is supplied for boys versus girls and white versus non-white British.

The gender, ethnic and socio-economic data is presented separately so we cannot see how these different factors impact on each other. This despite HMI’s known concern about the underperformance of disadvantaged white boys in particular. It would have been helpful to see that concern linked across to this one.

Overall, the findings do not seem particularly surprising. The large gaps between the percentages of students achieving four and three levels of progress respectively is to be expected, given the orthodoxy that students need only make a minimum of three levels of progress rather than the maximum progress of which they are capable.

The FSM gap of 17% at Grade B and above is actually substantively lower than the gap at Grade C and above which stood at 26.2% in 2011/12. Whether the A*/A gap demonstrates a further widening at the top end remains shrouded in mystery.

Although it is far too soon to have progression data, the report almost entirely ignores the impact of Level 6 on the emerging picture. And it forbears to mention the implications for any future data analysis – including trend analysis – of the decision to dispense with National Curriculum levels entirely with effect from 2016.

Clearly additional data of this kind might have overloaded the main body of the Report, but a data Annex could and should have been appended.

.

Why Ignore the Transition Matrices?

There is a host of information available about the performance of high attaining learners at Key Stage 4 and Key Stage 5 respectively, much of which I drew on for this post back in January 2013.

This applies to all state-funded schools and makes the point about high attainers’ underachievement in spades.

It reveals that, to some extent at least, there is a problem in selective schools too:

‘Not surprisingly (albeit rather oddly), 89.8% of students in selective schools are classified as ‘above Level 4’, whereas the percentage for comprehensive schools is 31.7%. Selective schools do substantially better on all the measures, especially the EBacc where the percentage of ‘above Level 4’ students achieving this benchmark is double the comprehensive school figure (70.7% against 35.0%). More worryingly, 6.6% of these high-attaining pupils in selective schools are not making the expected progress in English and 4.1% are not doing so in maths. In comprehensive school there is even more cause for concern, with 17.7% falling short of three levels of progress in English and 15.3% doing so in maths.’

It is unsurprising that selective schools tend to perform relatively better than comprehensive schools in maximising the achievement of high attainers, because they are specialists in that field.

But, by concentrating exclusively on comprehensive schools, Ofsted gives the false impression that there is no problem in selective schools when there clearly is, albeit not quite so pronounced.

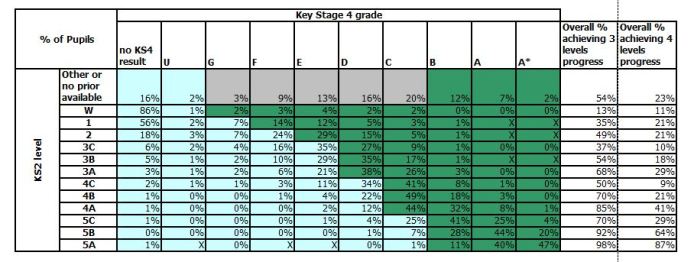

More recently, I have drawn attention to the enormous contribution that can be added to this evidence base by the Key Stage 2 to 4 Transition Matrices available in the Raise Online library.

.

Transition Matrices and student numbers English (top) and maths (bottom)

.

.

.

These have the merit of analysing progress to GCSE on the basis of National Curriculum sub-levels, and illustrate the very different performance of learners who achieve 5C, 5B and 5A respectively.

This means we are able to differentiate within the hugely wide Ofsted sample and begin to see how GCSE outcomes are affected by the strength of learners’ KS2 level 5 performance some five years previously.

The tables above show the percentages for English and maths respectively, for those completing GCSEs in 2012. I have also included the tables giving the pupil numbers in each category.

We can see from the percentages that:

- Of those achieving 5A in English, 47% go on to achieve an A* in the subject, whereas for 5B the percentage is 20% and for 5C as low as 4%.

- Similarly, of those achieving 5A in Maths, 50% manage an A*, compared with 20% for those with 5B and only 6% for those with 5C.

- Of those achieving 5A in English, 40% achieve Grade A, so there is a fairly even split between the top two grades. Some 11% achieve a Grade B and just 1% a Grade C.

- In maths, 34% of those with 5A at KS2 go on to secure a Grade A, so there is a relatively heavier bias in favour of A* grades. A slightly higher 13% progress to a B and 3% to a Grade C.

- The matrices show that, when it comes to the overall group of learners achieving Level 5, in English 10% get A*, 31% get A and 36% a B. Meanwhile, in maths, 20% get an A*, 31% an A and 29% a B. This illustrates perfectly the very significant advantage enjoyed by those with a high Level 5 compared with Level 5 as a whole.

- More worryingly, the progression made by learners who achieve upper Level 4s at Key Stage 2 tends to outweigh the progression of those with 5Cs. In English, 70% of those with 5C made 3 levels of progress and 29% made 4 levels of progress. For those with 4A, the comparable percentages were 85% and 41% respectively. For those with 4B they were 70% (so equal to the 5Cs) and 21% respectively.

- Turning to maths, the percentages of those with Level 5C achieving three and four levels of progress were 67% and 30% respectively, while for those with 4A they were 89% and 39% respectively and for 4B, 76% (so higher) and 19% (lower) respectively.

This suggests that, while there is undeniably an urgent and important issue at the very top, with half or fewer of 5As being translated into A* Grades, the bulk of the problem seems to be at the lower end of Level 5, where there is a conspicuous dip compared with both comparatively higher and comparatively lower attainers.

I realise that there are health warnings attached to the transition matrices, but one can immediately see how this information significantly enriches Ofsted’s relatively simplistic analysis.

.

Data About A Level Achievement and International Comparisons

The data supplied to illustrate progression to A level and international comparisons is comparatively limited.

For A Level:

- In 2012, 334 (so 20%) of a total of 1,649 non-selective 11-18 schools had no students achieving AAB+ Grades at A Level including at least two of the facilitating subjects. A footnote tells us that this applies only to 11-18 schools entering at least five pupils at A level. There is nothing about the controversy surrounding the validity of the ‘two facilitating subjects’ proviso (pages 4, 6, 14)

- Sutton Trust data is quoted from a 2008 publication suggesting that some 60,000 learners who were in the top quintile (20%) of performers in state schools at ages 11, 14 and 16 had not entered higher education by the age of 18; also that those known to have been eligible for FSM were 19% less likely than others to enter higher education by age 19. The most significant explanatory factor was ‘the level and nature of the qualifications’ obtained by those who had been FSM-eligible (page 15).

- A second Sutton Trust report is referenced showing that, from 2007-2009, students from independent schools were over twice as likely to gain admission to ‘one of the 30 most highly selective universities’ as students from non-selective state schools (48.2% compared with 18 %). However, this ‘could not be attributed solely to the schools’ average A level or equivalent results’ since 58% of applicants from the 30 strongest-performing comprehensive schools on this measure were admitted to these universities, compared with 87.1% from the highest-performing independent schools and 74.1% from the highest-performing grammar schools (pages 16-17)

- The only international comparisons data is drawn from PISA 2009. The Report uses performance against the highest level in the tests of reading, maths and science respectively. It notes that, in reading, England ranked 15th on this measure though above the OECD average, in maths England ranked 33rd and somewhat below the OECD average and in science England was a strong performer somewhat above the OECD average (page 17)

Apart from the first item, all this material is now at least four years old.

There is no attempt to link KS2 progression to KS5 achievement, which would have materially strengthened the argument (and which is the focus of one of the Report’s central recommendations).

Nor is there any effort to link the PISA assessment to GCSE data, by explaining the key similarities and differences between the two instruments and exploring what that tells us about particular areas of strength and weakness for high attainers in these subjects.

There is again, a wealth of pertinent data available, much of it presented in previous posts on this blog:

Given the relatively scant use of data in the Report, and the significant question marks about the manner in which it has been applied to support the argument, it is hardly surprising that much of the criticism levelled at Ofsted can be traced back to this issue.

All the material I have presented on this blog is freely available online and was curated by someone with no statistical expertise.

While I cannot claim my analysis is error-free, it seems to me that Ofsted’s coverage of the issue is impoverished by comparison. Not only is there too little data, there is too little of the right data to exemplify the issues under discussion.

But, as I have already stated, that is not sufficient reason to condemn the entire Report out of hand.

.

Exeter2 by Gifted Phoenix

The Qualitative Dimension of the Report

The Evidence Base

If you read some of the social media criticism heaped upon ‘The most able students’ you would be forgiven for thinking that the evidence base consisted entirely of a few dodgy statistics.

But Ofsted also drew on:

- Field visits to 41 non-selective secondary schools across England, undertaken in March 2013. The sample (which is reproduced as an Annex to the Report) was drawn from each of Ofsted’s eight regions and included schools of different sizes and ‘type’ and ‘different geographical contexts’. Twenty-seven were 11-18 schools, two are described as 11-19 schools, 11 were 11-16 schools and one admitted pupils at 14. Eighteen were academy converters. Inspectors spent a day in each school, discussing issues with school leaders, staff and pupils (asking similar questions to check sources against each other) and they ‘investigated analyses of the school’s [sic] current data’. We know that:

‘Nearly all of the schools visited had a broadly average intake in terms of their students’ prior attainment at the end of Key Stage 2, although this varied from year group to year group.’

Three selective schools were also visited ‘to provide comparison’ but – rather strangely – that comparative evidence was not used in the Report.

- A sample of 2,327 lesson observation forms collected from Section 5 inspections of a second sample of 109 non-selective secondary schools undertaken in academic year 2012/13. We are not told anything about the selection of this sample, so we have no idea how representative it was.

- A survey of 93 responses made by parents and carers to a questionnaire Ofsted placed on the website of the National Association for Able Children in Education (NACE)’. Ofsted also ‘sought the views of some key external organisations and individuals’ but these are not named. I have been able to identify just one organisation and one individual who were approached, which perhaps betrays a rather thin sample.

I have no great problem with the sample of schools selected for the survey. Some have suggested that 41 is too few. It falls short of the 50 mentioned in HMCI’s pre-publicity but it is enough, especially since Ofsted’s last Report in December 2009 drew on evidence from just 26 primary and secondary schools.

The second sample of lesson observations is more suspect, in that no information is supplied about how it was drawn. So it is entirely possible that it included all observations from those schools whose inspections were critical of provision for high attainers, or that all the schools were rated as underperforming overall, or against one of Ofsted’s key measures. There is a sin of omission here.

The parental survey is very small and, since it was filtered through a single organisation that focuses predominantly on teacher support, is likely to have generated a biased sample. The failure to engage a proper cross-section of organisations and individuals is regrettable: in these circumstances one should either consult many or none at all.

.

Survey Questions

Ofsted is comparatively generous with information about its Survey instrument.

There were two fundamental questions, each supported by a handful of supplementary questions:

‘Are the most able students in non-selective state secondary schools achieving as well as they should?’ (with ‘most able’ defined as set out above). This was supported by four supplementary questions:

- Are comprehensive schools challenging bright students in the way that the independent sector and selective system do?

- Do schools track progression effectively enough? Do they know how their most able students are doing? What enrichment programme is offered to the most able students and what is its impact?

- What is the effect of mixed ability classes on the most able students?

- What is the impact of early entry at GCSE on the most able students?

Why is there such disparity in admissions to the most prestigious universities between a small number of independent and selective schools and the great majority of state-maintained non-selective schools and academies?’

- What is the quality of careers advice and its impact on A level students, particularly in terms of their successful application to top universities? Are students receiving good advice and support on how to complete their UCAS forms/personal statements?

- Are the most able students from disadvantaged backgrounds as likely as the most able students from more affluent families to progress to top universities, and if not why?

- What are successful state schools doing to increase application success rates and what lessons can be learnt?

Evidence from the 41 non-selective schools was collected under six broad themes:

- ‘the leadership of the school

- the achievement of the most able students throughout the school

- the transfer and transition of these students from their primary schools and their induction into secondary school

- the quality of teaching, learning and assessment of the most able students

- the curriculum and extension activities offered to the most able student

- the support and guidance provided for the most able students, particularly when they were choosing subjects and preparing for university.’

But the survey also ‘focused on five key elements’ (page 32) which are virtually identical to the last five themes above.

.

Analysis of Key Findings

Top Level Conclusions

Before engaging in detail with the qualitative analysis from these sources, it is worth pausing to highlight two significant quantitative findings which are far more telling than those generated by the data analysis foregrounded in the Report.

Had I the good fortune to have reviewed the Report’s key findings prior to publication, I would have urged far greater prominence for:

- ‘The 2,327 lesson observation evidence forms… showed that the most able students in only a fifth of these lessons were supported well or better.’

- ‘In around 40% of the schools visited in the survey, the most able students were not making the progress of which they were capable. In a few of the schools visited, teachers did not even know who the most able students were.’

So, in a nutshell, one source of evidence suggests that, in 80% of lessons, support for the most able students is either inadequate or requires improvement.

Another source suggests that, in 40% of schools, the most able students are underachieving in terms of progress while, in a few schools, their identity is unknown.

And these findings apply not to a narrow group of the very highest attaining learners but, on the basis of Ofsted’s own definition, to over 50% of pupils!

Subject to the methodological concerns above, the samples appear sufficiently robust to be extrapolated to all English secondary schools – or the non-selective majority at least.

We do not need to apportion blame, or make schools feel that this is entirely their fault. But this is scandalous – indeed so problematic that it surely requires a concerted national effort to tackle it.

We will consider below whether the recommendations set out in the Report match that description, but first we need to engage with some of the qualitative detail.

The analysis below looks in turn at each of the six themes, in the order that they appear in the main body of the Report.

.

Theme 1 – Achievement of the Most Able Students

Key finding: ‘The most able students in non-selective secondary schools are not achieving as well as they should. In many schools, expectations of what the most able students should achieve are too low.’

Additional points:

- [Too] many of the students in the problematic 40% of surveyed schools ‘failed to attain the highest levels at GCSE and A level’.

- Academic progress in KS3 required improvement in 17 of the 41 schools. Data was neither accurate nor robust in seven of the 41. Progress differed widely by subject.

- At KS4, the most able were making less progress than other students in 19 of the 41 schools.

- At KS5, the most able were making ‘less than expected progress’ in one or more subjects at 17 of the 41 schools.

.

Theme 2 – Leadership and Management

Key Finding: ‘Leaders in our secondary schools have not done enough to create a culture of scholastic excellence, where the highest achievement in academic work is recognised as vitally important. Schools do not routinely give the same attention to the most able as they do to low-attaining students or those who struggle at school.’

Additional points:

- Nearly all school leaders claimed to be ambitious for their most able students, but this was not realised in practice in over 40% of the sample.

- In less effective schools initiatives were usually new or rudimentary and had not been evaluated.

- Students were taught mainly in mixed ability groups in about a third of the schools visited. Setting was typically restricted to core subjects and often introduced for English and science relatively late in KS3.

- This had no detrimental effect in ‘the very best schools’ but, in the less effective, work was typically pitched to average attainers.

- Seven schools had revised their policy on early GCSE entry because of a negative impact on the number of the most able achieving top grades.

- Leaders in the best schools showed high aspirations for their most able students, providing high-quality teaching and work matched to their needs. Results were well above average and high proportions achieved A*/A grades at GCSE and A level.

- The best leaders ensure their high aspirations are understood throughout the school community, set high expectations embodied in stretching targets, recruit strong staff and deploy them as specialists and create ‘a dynamic, innovative learning environment’.

.

Theme 3 – Transfer and Transition

Key Finding: ‘Transition arrangements from primary to secondary school are not effective enough to ensure that students maintain their academic momentum into Year 7. Information is not used carefully so that teachers can plan to meet the most able students’ needs in all lessons from the beginning of their secondary school career.’

Additional points:

- The quality of transition is much too variable. Arrangements were weak in over one quarter of schools visited. Work was repeated in KS3 or was insufficiently challenging. Opportunities were missed to extend and consolidate previous learning.

- Simple approaches were most effective, easier to implement in schools with few primary feeders or long-established cluster arrangements.

- In the best examples secondary schools supported the most able before transfer, through specialist teaching and enrichment/extension activities.

- In many schools activities were typically generic rather than targeted at the most able and many leaders didn’t know how effective they were for this group.

- In over a quarter of schools the most able ‘did not get off to a good start’ in Year 7 because expectations were too low, work was insufficiently demanding and pupils were under-challenged.

- Overall inspectors found serious weaknesses in this practice.

- Effective practice includes: pre-transfer liaison with primary teachers and careful discussion about the most able; gathering a wide range of data to inform setting or class groups; identifying the most able early and implementing support for them to maintain their momentum; and fully evaluating pre-transfer activities and adapting them in the light of that.

.

Exeter3 by Gifted Phoenix

.

Theme 4 – The Quality of Teaching, Learning and Assessment

Key Findings:

‘Teaching is insufficiently focused on the most able at KS3. In over two-fifths of the schools visited for the survey, students did not make the progress that they should, or that they were capable of, between the ages of 11 and 14. Students said that too much work was repetitive and undemanding in KS3. As a result, their progress faltered and their interest in school waned.

Many students became used to performing at a lower level than they are capable of. Parents or carers and teachers accepted this too readily. Students did not do the hard work and develop the resilience needed to perform at a higher level because more challenging tasks were not regularly demanded of them. The work was pitched at the middle and did not extend the most able. School leaders did not evaluate how well mixed-ability group teaching was challenging the most able students.’

Additional points:

- The reasons for slow progress varied between schools and subjects but included: failure to recognise and challenge the most able; variability in approaches across subjects and year groups; inconsistent application of school policy; and lack of focus by senior and middle leaders.

- Weaker provision demonstrated: insufficient tracking of the most able, inadequate rapid intervention strategies, insufficiently differentiated homework, failure to apply Pupil Premium funding and little evaluation of the impact of teaching and support.

- In a few schools the organisation of classes inhibited progress, as evidenced by limited knowledge of the effectiveness of differentiation in mixed ability settings and lack of challenge, particularly in KS3.

- Eight schools had moved recently to grouping by ability, particularly in core subjects. Others indicated they were moving towards setting, streaming or banding most subjects. Schools’ data showed this beginning to have a positive impact on outcomes.

.

Theme 5 – Curriculum and Extension Activities

Key Findings:

‘The curriculum and the quality of homework required improvement. The curriculum in KS3 and early entry to GCSE examination are among the key weaknesses found by inspectors. Homework and the programme of extension activities for the most able students, where they existed, were not checked routinely for their impact or quality. Students said that too much homework was insufficiently challenging; it failed to interest them, extend their thinking or develop their skills.

Inequalities between different groups of the most able students are not being tackled satisfactorily. The attainment of the most able students who are eligible for FSM, especially the most able boys, lags behind that of other groups. Few of the schools visited used the Pupil Premium funding to support the most able students from the poorest backgrounds.

Assessment, tracking and targeting are not used sufficiently well in many schools. Some of the schools visited paid scant attention to the progress of their most able students.’

Additional points:

- In over a quarter of schools visited, aspects of the curriculum, including homework, required improvement. In two schools the curriculum failed to meet the needs of the most able.

- In one in seven schools, leaders had made significant changes recently, including more focus on academic subjects and more setting.

- But schools did not always listen to feedback from their most able students. Many did not ask students how well the school was meeting their needs or how to improve further.

- In weaker schools students were rarely given extension work. Sixth form students reported insufficient opportunities to think reflectively and too few suggestions for wider, independent reading.

- Many in less effective schools felt homework could be more challenging. Few were set wider research or extension tasks.

- While some leaders said extra challenge was incorporated in homework, many students disagreed. Few school leaders were aware of the homework provided to these students. Many schools had limited strategies for auditing and evaluating its quality.

- Most school leaders said a wide range of extension tasks, extra-curricular and enrichment activities was provided for the most able, but these were usually for all students. Targeted activities, when undertaken, were rarely evaluated.

- Research suggests it is important to provide access to such activities for the most able students where parents are not doing so. Schools used Pupil Premium for this in only a few instances.

- The Premium was ‘generally spent on providing support for all underachieving and low-attaining students rather than on the most able students from disadvantaged backgrounds’.

- Strong, effective practice was exemplified by a curriculum well-matched to the needs of most able students, a good range and quality of extra-curricular activity, effective use of the Pupil Premium to enrich students’ curriculum and educational experience and motivating and engaging homework, tailored to students’ needs, designed to develop creativity and independence.

- In over a third of schools visited, tracking of the most able was ‘not secure, routine or robust’. Intervention was often too slow.

- In weaker schools, leaders were focused mainly on the C/D borderline; stronger schools also focused on A*/A grades too, believing their pupils could do better than ‘the B grade that is implied by the expected progress measure’.

- Some schools used assessment systems inconsistently, especially in some KS3 foundation subjects where there was insufficient or inaccurate data. In one in five schools, targets for the most able ‘lacked precision and challenge’.

- In a fifth of schools, senior leaders had introduced improved monitoring systems to hold staff to account, but implementation was often at a very early stage. Only in the best schools were such systems well established.

- The most effective included lesson observation, work scrutiny, data analysis and reviews of teacher planning. In the better schools students knew exactly what they needed to do to attain the next level/grade and received regular feedback on progress.

- The most successful schools had in place a wide range of strategies including: ensuring staff had detailed knowledge of the most able, their strengths and interests; through comprehensive assessment, providing challenging programmes and high quality support that met students’ needs; and rigorous tracking by year, department and key stage combined with swift intervention where needed.

- Many leaders had not introduced professional development focused on the most able students. Their needs had not been tackled by staff in over one fifth of schools visited, so teachers had not developed the required skills to meet their needs, or up-to-date knowledge of the Year 6 curriculum and assessment arrangements. Stronger schools were learning with and from their peers and had formed links with a range of external agencies.

.

Theme 6 – Support and Guidance for University Entry

Key Findings:

‘Too few of the schools worked with families to support them in overcoming the cultural and financial obstacles that stood in the way of the most able students attending university, particularly universities away from the immediate local area. Schools did not provide much information about the various benefits of attending different universities or help the most able students to understand more about the financial support available.

Most of the 11-16 schools visited were insufficiently focused on university entrance. These schools did not provide students with sufficiently detailed advice and guidance on all the post-16 options available.

Schools’ expertise in and knowledge about how to apply to the most prestigious universities was not always current and relevant. Insufficient support and guidance were provided to those most able students whose family members had not attended university.’

Additional points:

- Support and guidance varied in quality, accuracy and depth. Around half of schools visited ‘accepted any university as an option’. Almost a quarter had much to do to convince students and their families of the benefits of higher education, and began doing so too late.

- Data provided by 26 of the 29 11-18 schools showed just 16 students went to Oxbridge in 2011, one eligible for FSM, but almost half came from just two of the schools. Nineteen had no students accepted at Oxbridge. The 2012 figures showed some improvement with 26 admitted to Oxbridge from 28 schools, three of them FSM-eligible.

- In 2011, 293 students went to Russell Group universities, but only six were FSM eligible. By 2012 this had increased to 352, including 30 eligible for FSM, but over a quarter of the 352 came from just two schools.

- Factors inhibiting application to prestigious universities included pressure to stay in the locality, cost (including fees), aversion to debt and low expectations. Almost half of the schools visited tackled this through partnership with local universities.

- Schools did not always provide early or effective careers advice or information about the costs and benefits of attending university.

- Some schools showed a lack of up-to-date intelligence about universities and their entrance requirements, but one third of those visited provided high quality support and guidance.

- Some schools regarded going to any university as the indicator of success, disagreeing that it was appropriate to push students towards prestigious universities, rather than the ‘right’ institution for the student.

- Most of the 11-16 schools visited were insufficiently focused on university entrance. They did not provide sufficiently detailed advice on post-16 options and did not track students’ destinations effectively, either post-16 or post-18.

- The best schools: provided early on a planned programme to raise students’ awareness of university education; began engaging with students and parents about this as soon as they entered the school; provided support and guidance about subject choices, entry requirements and course content; supported UCAS applications; enabled students to visit a range of universities; and used alumni as role models.

.

Exeter4 by Gifted Phoenix

Ofsted’s Recommendations

There are two sets of recommendations in the Report, each with an associated commentary about the key constituents of good and bad practice. The first is in HMCI’s Foreword; the second in the main body of the Report.

.

HMCI’s Version

This leads with material from the data analysis, rather than some of the more convincing data from the survey, or at least a judicious blend of both sources.

He rightly describes the outcomes as unacceptable and inconsistent with the principle of comprehensive education, though his justification for omitting selective schools from the analysis is rather less convincing, especially since he is focused in part on narrowing the gap between the two as far as admission to prestigious universities is concerned.

Having pointed up deficiencies at whole school level and in lessons he argues that:

‘The term ‘special needs’ should be as relevant to the most able as it is to those who require support for their learning difficulties’

This is rather out of left field and is not repeated in the main body or the official recommendations. There are pros and cons to such a route – and it would anyway be entirely inappropriate for a population comprising over 50% of the secondary population.

HMCI poses ‘three key challenges’:

‘First, we need to make sure that our most able students do as well academically as those of our main economic competitors. This means aiming for A* and A grades and not being satisfied with less. Not enough has changed since 2009, when the PISA tests found that England’s teenagers were just over half as likely as those from other developed nations to reach the highest levels in mathematics in international tests.

The second challenge is to ensure, from early on, that students know what opportunities are open to them and develop the confidence to make the most of these. They need tutoring, guidance and encouragement, as well as a chance to meet other young people who have embraced higher education. In this respect, independent schools as well as universities have an important role to play in supporting state schools.

The third challenge is to ensure that all schools help students and families overcome cultural barriers to attending higher education. Many of our most able students come from homes where no parent or close relative has either experienced, or expects, progression to university. Schools, therefore, need to engage more effectively with the parents or carers of these students to tackle this challenge.’

This despite the fact that comparison with international competitors is almost entirely lacking from the Report, save for one brief section on PISA data.

The role of independent schools is also underplayed, while the role of universities is seen very much from the schools’ perspective – there is no effort to link together the ‘fair access’ and ‘most able’ agendas in any meaningful fashion.

Parental engagement is also arguably under-emphasised or, at least, confined almost exclusively to the issue of progression.

.

Ofsted’s Version

The ‘official’ text provides a standard overarching bullet point profile of poor and strong provision respectively.

- Poor provision is characterised by: ‘fragile’ primary/secondary transfer; placement in groups where teaching is not challenging; irregular progress checks; a focus on D/C borderline students at the expense of the more able; and failure to prepare students well for A levels.

- Strong provision features: leadership determined to improve standards for all students; high expectations of the most able amongst students, families and teachers; effective transition to sustain the momentum of the most able; early identification to inform tailoring of teaching and the curriculum; curricular flexibility to permit challenge and extension; grouping to support stretch from the start of secondary school; expert teaching, formative assessment and purposeful homework; effective training and capacity for teachers to learn from each other; close monitoring of progress to inform rapid intervention where necessary; and effective support for application to prestigious universities.

A series of 13 recommendations is provided, alongside three Ofsted commitments. Ten of the 13 are aimed at schools and three at central Government.

I have set out the recommendations in the table below, alongside those from the previous Report, published in 2009.

| 2009 Report |

2013 Report |

| Central Government |

Central Government |

| Ensure planned catalogue of learning and professional development opportunities meets the needs of parents, schools and LAs |

DfE to ensure parents receive annual report recording whether students are on track to achieve as well as they should in national tests and exams |

| Ensure LAs hold schools more rigorously to account for the impact of their G&T provision |

DfE to develop progress measures from KS2 to KS4 and KS5 |

|

DfE to promote new destination data showing progression to (Russell Group) universities |

|

Ofsted will focus inspections more closely on teaching and progress of most able, their curriculum and the information, advice and guidance provided to them |

|

Ofsted will consider in more detail during inspection how well Pupil Premium is used to support disadvantaged most able |

|

Ofsted will report inspection findings about this group more clearly in school, sixth form and college reports |

| Local Authorities |

Local Authorities |

| Hold schools more rigorously to account for the impact of their G&T provision |

|

| Encourage best practice by sharing with schools what works well and how to access appropriate resources and training |

|

| Help schools produce clearer indicators of achievement and progress at different ages |

|

| Schools |

Schools |

| Match teaching to pupils’ individual needs |

Develop culture and ethos so needs of most able are championed by school leaders |

| Listen to pupil feedback and act on it |

Help most able to leave school with best qualifications by developing skills, confidence and attitudes needed to succeed at the best universities |

| Inform parents and engage them more constructively |

Improve primary-secondary transfer so all Year 7 teachers know which students achieved highly and what aspects of the curriculum they studied in Year 6, and use this to inform KS3 teaching. |

| Use funding to improve provision through collaboration |

Ensure work remains challenging throughout KS3 so most able make rapid progress. |

| Ensure lead staff have strategic clout |

Ensure leaders evaluate mixed ability teaching so most able are sufficiently challenged and make good progress |

| Ensure rigorous audit and evaluation processes |

Evaluate homework to ensure it is sufficiently challenging |

|

Give parents better and more frequent information about what their children should achieve and raise expectations where necessary. |

|

Work more closely with families, especially first generation HE applicants and FSM-eligible to overcome cultural and financial obstacles to HE application |

|

Develop more knowledge and expertise to support applications to the most prestigious universities |

|

Publish more widely the university destinations of their students |

TABLE 1: COMPARING OFSTED RECOMMENDATIONS IN 2009 AND 2013

The comparison serves to illustrate the degree of crossover between the two Reports – and to what extent the issues raised in the former remain pertinent four years on.

The emboldened Items in the left-hand column are still outstanding and are not addressed in the latest Report. There is nothing about providing support for schools from the centre; and nothing whatsoever about the role of the ‘middle tier’, however that is composed. Ofsted’s new Report might have been enriched by some cross-reference to its predecessor.

The three recommendations directed at the centre are relatively limited in scope – fundamentally restricted to elements of the status quo and probably demanding negligible extra work or resource

- The reference to an annual report to parents could arguably be satisfied by the existing requirements, which are encapsulated in secondary legislation.

- It is not clear whether promoting the new destination measures requires anything more than their continuing publication – the 2013 version is scheduled for release this very week.

- The reference to development of progress measures may be slightly more significant but probably reflects work already in progress. The consultation document on Secondary School Accountability proposed a progress measure based on a new ‘APS8’ indicator, calculated through a Value Added method and using end KS2 results in English and maths as a baseline:

‘It will take the progress each pupil makes between Key Stage 2 and Key Stage 4 and compare that with the progress that we expect to be made by pupils nationally who had the same level of attainment at Key Stage 2 (calculated by combining results at end of Key Stage 2 in English and mathematics).’

However this applies only to KS4, not KS5, and we are still waiting to discover how the KS2 baseline will be graded from 2016 when National Curriculum levels disappear.

This throws attention back on the Secretary of State’s June 2012 announcement, so far unfulfilled by any public consultation:

‘In terms of statutory assessment, however, I believe that it is critical that we both recognise the achievements of all pupils, and provide for a focus on progress. Some form of grading of pupil attainment in mathematics, science and English will therefore be required, so that we can recognise and reward the highest achievers as well as identifying those that are falling below national expectations. We will consider further the details of how this will work.’

.

The Balance Between Challenge and Support

It is hard to escape the conclusion that Ofsted believe inter-school collaboration, the third sector and the market can together provide all the support that schools can need (while the centre’s role is confined to providing commensurate challenge through a somewhat stiffened accountability regime).

After four years of school-driven gifted education, I am not entirely sure I share their confidence that schools and the third sector can rise collectively to that challenge.

They seem relatively hamstrung at present by insufficient central investment in capacity-building and an unwillingness on the part of key players to work together collaboratively to update existing guidance and provide support. The infrastructure is limited and fragmented and leadership is lacking.

As I see it, there are two immediate priorities:

- To provide and maintain the catalogue of learning opportunities and professional support mentioned in Ofsted’s 2009 report; and

- To update and disseminate national guidance on what constitutes effective whole school gifted and talented education.

The latter should in my view be built around an updated version of the Quality Standards for gifted education, last refreshed in 2010. It should be adopted once more as the single authoritative statement of effective practice which more sophisticated tools – some, such as the Challenge Award, with fairly hefty price tags attached – can adapt and apply as necessary.

The Table appended to this post maps the main findings in both the 2009 and 2013 Ofsted Reports against the Standards. I have also inserted a cross in those sections of the Standards which are addressed by the main text of the more recent Report.

One can see from this how relevant the Standards remain to discussion of what constitutes effective whole school practice.

But one can also identify one or two significant gaps in Ofsted’s coverage, including:

- identification – and the issues it raises about the relationship between ability and attainment

- the critical importance of a coherent, thorough, living policy document incorporating an annually updated action plan for improvement

- the relevance of new technology (such as social media)

- the significance of support for affective issues, including bullying, and

- the allocation of sufficient resources – human and financial – to undertake the work.

.

Exeter5 by Gifted Phoenix

Reaction to the Report

I will not trouble to reproduce some of the more vituperative comment from certain sources, since I strongly suspect much of it to be inspired by personal hostility to HMCI and to gifted education alike.

- To date there has been no formal written response from the Government although David Laws recorded one or two interviews such as this which simply reflects existing reforms to accountability and qualifications. At the time of writing, the DfE page on Academically More Able Pupils has not been updated to reflect the Report.

- The Opposition criticised the Government for having ‘no plan for gifted and talented children’ but did not offer any specific plan of their own.

- The Sutton Trust called the Report ‘A wake-up call to Ministers’ adding:

‘Schools must improve their provision, as Ofsted recommends. But the Government should play its part too by providing funding to trial the most effective ways to enable our brightest young people to fulfil their potential. Enabling able students to fulfil their potential goes right to the heart of social mobility, basic fairness and economic efficiency.’

Contrary to my expectations, there was no announcement arising from the call for proposals the Trust itself issued back in July 2012 (see word attachment at bottom). A subsequent blog post called for:

‘A voluntary scheme which gives head teachers an incentive – perhaps through a top-up to their pupil premium or some other matched-funding provided centrally – to engage with evidence based programmes which have been shown to have an impact on the achievement of the most able students.’

‘We warned the Government in 2010 when it scrapped the gifted and talented programme that this would be the result. Many schools are doing a fantastic job in supporting these children. However we know from experience that busy schools will often only have time to focus on the latest priorities. The needs of the most able children have fallen to the bottom of the political and social agenda and it’s time to put it right to the top again.’

‘It is imperative that Ofsted, schools and organisations such as NACE work in partnership to examine in detail the issues surrounding this report. We need to disseminate more effectively what works. There are schools that are outstanding in how they provide for the brightest students. However there has not been enough rigorous research into this.’

- Within the wider blogosphere, Geoff Barton was first out of the traps, criticising Ofsted for lack of rigour, interference in matters properly left to schools, ‘fatuous comparisons’ and ‘easy soundbites’.

- The same day Tom Bennett was much more supportive of the Report and dispensed some commonsense advice based firmly on his experience as a G&T co-ordinator.

- Then Learning Spy misunderstood Tom’s suggestions about identification asking ‘how does corralling the boffins and treating them differently’ serve the aim of high expectations for all? He far preferred Headguruteacher’s advocacy for a ‘teach to the top’ curriculum, which is eminently sensible.

- Accordingly, Headguruteacher contributed The Anatomy of High Expectations which drew out the value of the Report for self-evaluation purposes (so not too different to my call for a revised IQS).

- Finally Chris Husbands offered a contribution on the IoE Blog which also linked Ofsted’s Report to the abolition of National Curriculum levels, reminding us of some of the original design features built in by TGAT but never realised in practice.

Apologies to any I have missed!

As for yours truly, I included the reactions of all the main teachers’ associations in the collection of Tweets I posted on the day of publication.

I published Driving Gifted Education Forward, a single page proposal for the kind of collaborative mechanism that could bring about system-wide improvement, built on school-to-school collaboration. It proposes a network of Learning Schools, complementing Teaching Schools, established as centres of excellence with a determinedly outward-looking focus.

And I produced a short piece about transition matrices which I have partly integrated into this post.

Having all but completed this extended analysis, have I changed the initial views I Tweeted on the day of publication?

.

.

Well, not really. My overall impression is of a curate’s egg, whose better parts have been largely overlooked because of the opprobrium heaped on the bad bits.

.

Bishop: ‘I’m afraid you’ve got a bad egg Mr Jones’, Curate: ‘Oh, no, my Lord, I assure you that parts of it are excellent!’

.

The Report might have had a better reception had the data analysis been stronger, had the most significant messages been given comparatively greater prominence and had the tone been somewhat more emollient towards the professionals it addresses, with some sort of undertaking to underwrite support – as well as challenge – from the centre.

The commitments to toughen up the inspection regime are welcome but we need more explicit details of exactly how this will be managed, including any amendments to the framework for inspection and supporting guidance. Such adjustments must be prominent and permanent rather than tacked on as an afterthought.

We – all of us with an interest – need to fillet the key messages from the text and integrate them into a succinct piece of guidance as I have suggested, but carefully so that it applies to every setting and has built-in progression for even the best-performing schools. That’s what the Quality Standards did – and why they are still needed. Perhaps Ofsted should lead the revision exercise and incorporate them wholesale into the inspection framework.

As we draw down a veil over the second of these three ‘Summer of Love’ publications, what are the immediate prospects for a brighter future for English gifted education?

Well, hardly incandescent sunshine, but rather more promising than before. Ofsted’s Report isn’t quite the ‘landmark’ HMCI Wilshaw promised and it won’t be the game changer some of us had hoped for, but it’s better than a poke in the eye with the proverbial blunt stick.

Yet the sticking point remains the capacity of schools, organisations and individuals to set aside their differences and secure the necessary collateral to work collectively together to bring about the improvements called for in the Report.

Without such commitment too many schools will fail to change their ways.

.

GP

June 2013

.

.

ANNEX: MAPPING KEY FINDINGS FROM THE 2009 AND 2013 REPORTS AGAINST THE IQS

| IQS Element |

IQS Sub-element |

Ofsted 2009 |

Ofsted 2013 |

|

|

|

|

| Standards and progress |

Attainment levels high and progress strong |

Schools need more support and advice about standards and expectations |

Most able aren’t achieving as well as they should. Expectations are too low.65% who achieved KS2 L5 in English and maths failed to attain GCSE A*/A gradesTeaching is insufficiently focused on the most able at KS3Inequalities between different groups aren’t being tackled satisfactorily |

|

SMART targets set for other outcomes |

|

x |

| Effective classroom provision |

Effective pedagogical strategies |

Pupil experienced inconsistent level of challenge |

x |

|

Differentiated lessons |

|

x |

|

Effective application of new technologies |

|

|

| Identification |

Effective identification strategies |

|

x |

|

Register is maintained |

|

|

|

Population is broadly representative of intake |

|

|

| Assessment |

Data informs planning and progression |

|

Assessment, tracking and targeting not used sufficiently well in many schools |

|

Effective target-setting and feedback |

|

x |

|

Strong peer and self-assessment |

|

|

| Transfer and transition |

Effective information transfer between classes, years and institutions |

|

Transition doesn’t ensure students maintain academic momentum into Year 7 |

| Enabling curriculum entitlement and choice |

Curriculum matched to learners’ needs |

Pupils’ views not reflected in curriculum planning |

The KS3 curriculum is a key weakness, as is early GCSE entry |

|

Choice and accessibility to flexible pathways |

|

|

| Leadership |

Effective support by SLT, governors and staff |

Insufficient commitment in poorer performing schools |

School leaders haven’t done enough to create a culture of scholastic excellence.Schools don’t routinely give the same attention to most able as low-attaining or struggling students. |

| Monitoring and evaluation |

Performance regularly reviewed against challenging targets |

Little evaluation of progression by different groups |

x |

|

Evaluation of provision for learners to inform development |

|

x |

| Policy |

Policy is integral to school planning, reflects best practice and is reviewed regularly |

Many policies generic versions from other schools or the LA;Too much inconsistency and incoherence between subjects |

|

| School ethos and pastoral care |

Setting high expectations and celebrating achievement |

|

Many students become used to performing at a lower level than they are capable of. Parents and teachers accept this too readily. |

|

Support for underachievers and socio-emotional needs |

|

|

|

Support for bullying and academic pressure/opportunities to benefit the wider community |

|

|

| Staff development |

Effective induction and professional development |

|

x |

|

Professional development for managers and whole staff |

|

x |

| Resources |

Appropriate budget and resources applied effectively |

|

|

| Engaging with the community, families and beyond |

Parents informed, involved and engaged |

Less than full parental engagement |

Too few schools supporting families in overcoming cultural and financial obstacles to attending university |

|

Effective networking and collaboration with other schools and organisations |

Schools need more support to source best resources and trainingLimited collaboration in some schools; little local scrutiny/accountability |

Most 11-16 schools insufficiently focused on university entranceSchools’ expertise and knowledge of prestigious universities not always current and relevant |

| Learning beyond the classroom |

Participation in a coherent programme of out-of-hours learning |

Link with school provision not always clear; limited evaluation of impact |

Homework and extension activities were not checked routinely for impact and quality |