.

This post considers Ofsted’s survey report ‘The most able students: An update on progress since June 2013’ published on 4 March 2015.

It is organised into the following sections:

- The fit with earlier analysis

- Definitions and the consequent size of Ofsted’s ‘most able’ population

- Evidence base – performance data and associated key findings

- Evidence base – inspection and survey evidence and associated key findings

- Ofsted’s recommendations and overall assessment

.

How this fits with earlier work

The new Report assesses progress since Ofsted’s previous foray into this territory some 21 months ago: ‘The most able students: Are they doing as well as they should in our non-selective secondary schools?’ (June 2013)

The autopsy I performed on the original report was severely critical.

It concluded:

‘My overall impression is of a curate’s egg, whose better parts have been largely overlooked because of the opprobrium heaped on the bad bits.

The Report might have had a better reception had the data analysis been stronger, had the most significant messages been given comparatively greater prominence and had the tone been somewhat more emollient towards the professionals it addresses, with some sort of undertaking to underwrite support – as well as challenge – from the centre.’

In May 2014, almost exactly mid-way between that Report and this, I published an analysis of the quality of Ofsted reporting on support for the most able in a sample of Section 5 secondary school inspection reports.

This uncovered a patchy picture which I characterised as ‘requiring improvement’.

It noted the scant attention given by inspectors to high-attaining disadvantaged learners and called for Ofsted to publish guidance to clarify, for inspectors and schools alike, what they mean by the most able and their expectations of what support schools should provide.

In December 2014, I published ‘HMCI ups the ante on the most able’ which drew attention to commitments in HMCI’s Annual Report for 2013/14 and the supporting documentation released alongside it.

I concluded that post with a series of ten recommendations for further action by Ofsted and other central government bodies that would radically improve the chances of achieving system-wide improvement in this territory.

The new Report was immediately preceded by a Labour commitment to introduce a £15m Gifted and Talented Fund if successful in the forthcoming General Election.

This short commentary discusses that and sets out the wider political context into which Ofsted’s new offering will fall.

.

Reactions to Ofsted’s Report

Before considering the Report’s content, it may be helpful to complete this context-setting by charting immediate reactions to it.

- DfE’s ‘line to take, as quoted by the Mail, is:

‘We know that the best schools do stretch their pupils. They are the ones with a no-excuses culture that inspires every student to do their best.

Our plan for education is designed to shine a bright light on schools which are coasting, or letting the best and brightest fall by the wayside.

That is why we are replacing the discredited system which rewarded schools where the largest numbers of pupils scraped a C grade at GCSE.

Instead we are moving to a new system which encourages high-achievers to get the highest grades possible while also recognising schools which push those who find exams harder.’

‘David Cameron’s government has no strategy for supporting schools to nurture their most able pupils. International research shows we perform badly in helping the most gifted pupils. We’re going to do something about that. Labour will establish a Gifted and Talented Fund to equip schools with the most effective strategies for stretching their most able pupils.’

- ASCL complains that the Report ‘fails to recognise that school leaders have done an extraordinary job in difficult circumstances in raising standards and delivering a good education for all children’. It is also annoyed because Ofsted’s press release:

‘…should have focused on the significant amount of good practice identified in the report rather than leading with comments that some schools are not doing enough to ensure the most able children fulfil their potential.’

.

.

- NAHT makes a similarly generic point about volatility and change:

‘The secondary sector has been subject to massive structural change over the past few years. It’s neither sensible nor accurate to accuse secondary schools of failure. The system itself is getting in the way of success…

…Not all of these changes are bad. The concern is that the scale and pace of them will make it very hard indeed to know what will happen and how the changes will interact….

…The obvious answer is quite simple: slow down and plan the changes better; schedule them far enough ahead to give schools time to react….

But the profession also needs to ask what it can do. One answer is not to react so quickly to changes in league table calculations – to continue to do what is right…’

There was no official reaction from ATL, NASUWT or NUT.

Turning to the specialist organisations:

‘If the failure reported by Ofsted was about any other issue there would be a national outcry.

This cannot be an issue laid at the door of schools alone, with so many teachers working hard, and with no budget, to support these children.

But in some schools there is no focus on supporting high potential learners, little training for teachers to cope with their educational needs, and a naive belief that these children will succeed ‘no matter what’.

Ofsted has shown that this approach is nothing short of a disaster; a patchwork of different kinds of provision, a lack of ambitious expectations and a postcode lottery for parents.

We need a framework in place which clearly recognises best practice in schools, along with a greater understanding of how to support these children with high learning potential before it is too late.’

‘NACE concurs with both the findings and the need for urgent action to be taken to remove the barriers to high achievement for ALL pupils in primary and secondary schools…

… the organisation is well aware that nationally there is a long way to go before all able children are achieving in line with their abilities.’

‘Today’s report demonstrates an urgent need for more dedicated provision for the highly able in state schools. Ofsted is right to describe the situation as ‘especially disappointing’; too many of our brightest students are being let down…

…We need to establish an effective national programme to support our highly able children particularly those from low and middle income backgrounds so that they have the stretch and breath they need to access the best universities and the best careers.’

Summing up, the Government remains convinced that its existing generic reforms will generate the desired improvements.

There is so far no response, from Conservatives or Liberal Democrats, to the challenge laid down by Labour, which has decided that some degree of arms-length intervention from the centre is justified.

The headteacher organisations are defensive because they see themselves as the fall guys, as the centre increasingly devolves responsibility through a ‘school-driven self-improving’ system that cannot yet support its own weight (and might never be able to do so, given the resource implications of building sufficient capacity).

But they cannot get beyond these generic complaints to address the specific issues that Ofsted presents. They are in denial.

The silence of the mainstream teachers’ associations is sufficient comment on the significance they attach to this issue.

The specialist lobby calls explicitly for a national framework, or even the resurrection of a national programme. All are pushing their own separate agendas over common purpose and collaborative action.

Taken together, this does not bode well for Ofsted’s chances of achieving significant traction.

.

Ofsted’s definitions

.

Who are the most able?

Ofsted is focused exclusively on non-selective secondary schools, and primarily on KS3, though most of the data it publishes relates to KS4 outcomes.

My analysis of the June 2013 report took umbrage at Ofsted’s previous definition of the most able:

‘For the purpose of this survey ‘most able’ is defined as the brightest students starting secondary school in Year 7 attaining Level 5 or above, or having the potential to attain Level 5 and above, in English (reading and writing) and/or mathematics at the end of Key Stage 2. Some pupils who are new to the country and are learning English as an additional language, for example, might not have attained Level 5 or beyond at the end of Key Stage 2 but have the potential to achieve it.’

On this occasion, the definition is similarly based on prior attainment at KS2, but the unquantified proportion of learners with ‘the potential to attain Level 5 or above’ are removed, meaning that Ofsted is now focused exclusively on high attainers:

‘For this report, ‘most able’ refers to students starting secondary school in Year 7 having attained Level 5 or above in English (reading and writing) and/or mathematics at the end of Key Stage 2.’

This reinforces the unsuitability of the term ‘most able’, on the grounds that attainment, not ability, is the true focus.

Ofsted adds for good measure:

‘There is currently no national definition for most able’

They fail to point out that the Performance Tables include a subtly different definition of high attainers, essentially requiring an APS of 30 points or higher across Key Stage 2 tests in the core subjects.

The 2014 Secondary Performance Tables show that this high attainer population constitutes 32.3% of the 2014 GCSE cohort in state-funded schools.

The associated SFR indicates that high attainers account for 30.9% of the cohort in comprehensive schools (compared with 88.8% in selective schools).

But Ofsted’s definition is wider still. The SFR published alongside the 2014 Primary Performance Tables reveals that, in 2014:

- 29% of pupils achieved Level 5 or above in KS2 reading and writing

- 44% of pupils achieved Level 5 or above in KS2 Maths and

- 24% of pupils achieved Level 5 or above in KS2 reading, writing and maths.

If this information is fed into a Venn diagram, it becomes evident that, this academic year, the ‘most able’ constitute 49% of the Year 7 cohort.

That’s right – almost exactly half of this year’s Year 7s fall within Ofsted’s definition.

.

.

The population is not quite so large if we focus instead on KS2 data from 2009, when the 2014 GCSE cohort typically took their KS2 tests, but even that gives a combined total of 39%.

We can conclude that Ofsted’s ‘most able’ population is approximately 40% of the KS4 cohort and approaching 50% of the KS3 cohort.

This again calls into question Ofsted’s terminology, since the ‘most’ in ‘most able’ gives the impression that they are focused on a much smaller population at the top of the attainment distribution.

We can check the KS4 figure against numerical data provided in the Report, to demonstrate that it applies equally to non-selective schools, ie once selective schools have been removed from the equation.

The charts in Annex A of the Report give the total number of pupils in non-selective schools with L5 outcomes from their KS2 assessments five years before they take GCSEs:

- L5 maths and English = 91,944

- L5 English (reading and writing) = 138,789

Assuming there is no double-counting, this gives us a total population of 212,185 in 2009.

I could not find a reliable figure for the number of KS2 test takers in 2009 in state-funded primary schools, but the equivalent in the 2011 Primary Performance Tables is 547,025.

Using that, one can calculate that those within Ofsted’s definition constitute some 39% of the 2014 GCSE cohort in non-selective secondary schools. The calculations above suggest that the KS3 cohort will be some ten percentage points larger.

.

.

Distribution between schools

Of course the distribution of these students between schools will vary considerably.

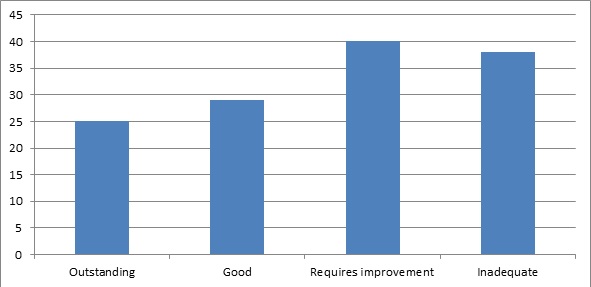

The 2014 Secondary Performance Tables illustrate this graphically through their alternative ‘high attainers’ measure. The cohort information provides the percentage of high attainers in the GCSE cohort in each school.

The highest recorded percentage in a state-funded comprehensive school is 86%, whereas 92 state-funded schools record 10% or fewer high attainers and just over 650 have 20% or fewer in their GCSE cohort.

At the other extreme, 21 non-selective state-funded schools are at 61% or higher, 102 at 51% or higher and 461 at 41% or higher.

However, the substantial majority – about 1,740 state-funded, non-selective schools – fall between 21% and 40%.

The distribution is shown in the graph below.

.

Percentage of high attainers within each state-funded non-selective secondary school’s cohort 2014 (Performance Tables measure)

.

Ofsted approaches the issue differently, by looking at the incidence of pupils with KS2 L5 in English, maths and both English and maths.

Their tables (again in Annex A of the Report) show that, within the 2014 GCSE cohort there were:

- 2,869 non-selective schools where at least one pupil previously attained a L5 in KS2 English

- 2,875 non-selective schools where at least one pupil previously attained a L5 in KS2 maths and

- 2,859 non-selective schools where at least one pupil previously attained l5 in KS2 English and maths.

According to the cohort data in the 2014 Secondary Performance Tables, this suggests that roughly 9% of state-funded non-selective secondary schools had no pupils in each of these categories within the relevant cohort. (It is of course a different 9% in each case.)

Ofsted’s analysis shows that the lowest decile of schools in the distribution of students with L5 in English will have up to 14 of them.

Similarly the lowest decile for L5 in maths will have up to 18 pupils, and the lowest decile for L5 in maths and English combined will have up to 10 pupils.

Assuming a top set typically contains at least 26 pupils, 50% of state-funded, non-selective schools with at least one pupil with L5 English have insufficient students for one full set. The comparable percentage for maths is 30%.

But Ofsted gives no hint of what might constitute a critical mass of high attainers, appearing to suggest that it is simply a case of ‘the more the better’.

Moreover, it seems likely that Ofsted might simply be identifying the incidence of disadvantage through the proxy of high attainers.

This is certainly true at the extremes of the distribution based on the Performance Tables measure.

- Amongst the 92 schools with 10% or fewer high attainers, 53 (58%) have a cohort containing 41% or more disadvantaged students.

- By comparison, amongst the 102 schools with 51% or more high attainers, not one school has such a high proportion of disadvantaged students, indeed, 57% have 10% or fewer.

.

Disadvantage

When Ofsted discusses the most able from disadvantaged backgrounds, its definition of disadvantage is confined to ‘Ever-6 FSM’.

The Report does not provide breakdowns showing the size of this disadvantaged population in state-funded non-selective schools with L5 English or L5 maths.

It does tell us that 12,150 disadvantaged students in the 2014 GCSE cohort had achieved KS2 L5 in both English and maths. They form about 13.2% of the total cohort achieving this outcome.

If we assume that the same percentage applies to the total populations achieving L5 English only and L5 maths only, this suggests the total size of Ofsted’s disadvantaged most able population within the 2014 GCSE cohort in state-funded, non-selective schools is almost exactly 28,000 students.

Strangely, the Report does not analyse the distribution of disadvantaged high attainers, as opposed to high attainers more generally, even though the text mentions this as an issue in passing.

One would expect that the so called ‘minority effect’ might be even more pronounced in schools where there are very few disadvantaged high attainers.

.

Ofsted’s evidence base: Performance data

The Executive Summary argues that analysis of national performance data reveals:

‘…three key areas of underperformance for the most able students. These are the difference in outcomes between:

- schools where most able students make up a very small proportion of the school’s population and those schools where proportions are higher

- the disadvantaged most able students and their better off peers

- the most able girls and the most able boys.

If the performance of the most able students is to be maximised, these differences need to be overcome.’

As noted above, Ofsted does not separately consider schools where the incidence of disadvantaged most able students is low, nor does it look at the interaction between these three categories.

It considers all three areas of underperformance through the single prism of prior attainment in KS2 tests of English and maths.

The Report also comments on a fourth dimension: the progression of disadvantaged students to competitive universities. Once again this is related to KS2 performance.

There are three data-related Key Findings:

- ‘National data show that too many of the most able students are still being let down and are failing to reach their full potential. Most able students’ achievement appears to suffer even more when they are from disadvantaged backgrounds or when they attend a school where the proportion of previously high-attaining students is small.’

- ‘Nationally, too many of our most able students fail to achieve the grades they need to get into top universities. There are still schools where not a single most able student achieves the A-level grades commonly preferred by top universities.’

- ‘The Department for Education has developed useful data about students’ destinations when they leave Key Stage 4. However, information about students’ destinations when they leave Key Stage 5 is not as comprehensive and so is less useful.’

The following sections look at achievement compared with prior attainment, followed by each of the four dimensions highlighted above.

.

GCSE attainment compared with KS2 prior attainment

Ofsted’s approach is modelled on the transition matrices, as applied to non-selective schools, comparing KS2 test performance in 2009 with subsequent GCSE performance in 2014.

Students with KS2 L5 are expected to make at least three levels of progress, to GCSE Grade B or higher, but this is relatively undemanding for high attainers, who should ideally be aiming for A/A* grades.

Ofsted presents two charts which illustrate the relatively small proportions who are successful in these terms – and the comparatively large proportions who undershoot even a grade B.

.

.

- In English, 39% manage A*/A grades while 77% achieve at least a Grade B, meaning that 23% achieve C or below.

- In maths, 42% achieve A*/A grades, 76% at least a B and so 24% achieve C or lower.

- In English and maths combined, 32% achieve A*/A grades in both subjects, 73% manage at least 2 B grades, while 27% fall below this.

Approximately one in four high attainers is not achieving each of these progression targets, even though they are not particularly demanding.

The Report notes that, in selective schools, the proportion of Level 5 students not achieving at least a Grade B is much lower, at 8% in English and 6% in maths.

Even allowing for the unreliability of these ‘levels of progress’ assumptions, the comparison between selective and non-selective schools is telling.

.

The size of a school’s most able population

The Report sets out evidence to support the contention that ‘the most able do best when there are more of them in a school’ (or, more accurately, in their year group).

It provides three graphs – for English, for maths and for maths and English combined – which divide non-selective schools with at least one L5 student into deciles according to the size of that L5 population.

These show consistent increases in the proportion of students achieving GCSE Grade B and above and Grades A*/A, with the lowest percentages for the lowest deciles and vice versa.

Comparing the bottom (fewest L5) and top (most L5) deciles:

- In English 27% of the lowest decile achieved A*/A and 67% at least a B, whereas in the highest decile 48% achieved A*/A and 83% at least B.

- In maths 28% of the bottom decile recorded A*/A while 65% managed at least a B, whereas in the top decile 54% achieved A*/A and 83% at least a B.

- In maths and English combined, the lowest decile schools returned 17% A*/A grades and 58% at B or above, while in the highest decile the percentages were 42% and 81% respectively.

Selective schools record higher percentages than the highest decile on all three measures.

There is a single reference to the impact of sublevels, amply evidenced by the transition matrices.

‘For example, in schools where the lowest proportions of most able students had previously gained Level 5A in mathematics, 63% made more than expected progress. In contrast, in schools where the highest proportion of most able students who had previously attained Level 5A in mathematics, 86% made more than expected progress.’

Ofsted does not draw any inferences from this finding.

As hinted above, one might want to test the hypothesis that there may be an association with setting – in that schools with sufficient Level 5 students to constitute a top set might be relatively more successful.

Pursued to its logical extreme the finding would suggest that Level 5 students will be most successful where they are all taught together.

Interestingly, my own analysis of schools with small high attainer populations (10% or less of the cohort), derived from the 2014 Secondary Performance Tables, shows just how much variation there can be in the performance of these small groups when it comes to the standard measures:

- 5+ A*-C grades including English and maths varies from 44% to 100%

- EBacc ranges from 0% to 89%

- Expected progress in English varies between 22% and 100% and expected progress in maths between 27% and 100%.

This is partly a function of the small sample sizes. One suspects that Ofsted’s deciles smooth over similar variations.

But the most obvious point is that already emphasised in the previous section – the distribution of high attainers seems in large part a proxy for the level of advantage in a school.

Viewed from this perspective, Ofsted’s data on the variation in performance by distribution of high attaining students seems unsurprising.

.

Excellence gaps

Ofsted cites an ‘ever 6’ gap of 13 percentage points at GCSE grade B and above in English (66% compared with 79%) and of 17 percentage points in maths (61% compared with 78%).

Reverting again to progression from KS2, the gap between L5 ‘ever 6 FSM’ and other students going on to achieve A*/A grades in both English and maths is also given as 17 percentage points (20% versus 37%). At Grade B and above the gap is 16 points (59% compared with 75%).

A table is supplied showing progression by sub-level in English and maths separately.

.

.

A footnote explains that the ‘ever 6 FSM’ population with L5a in English was small, consisting of just 136 students.

I have transferred these excellence gaps to the graph below, to illustrate the relationship more clearly.

.

GCSE attainment gaps between advantaged and disadvantaged learners by KS2 prior attainment

.

It shows that, for grades A*-B, the size of the gap reduces the higher the KS2 sub-level, but the reverse is true at grades A*/A, at least as far as the distinction between 5c and 5b/a is concerned. The gaps remain similar or identical for progression from the higher two sub-levels.

This might suggest that schools are too little focused on pushing high-attaining disadvantaged learners beyond grade B.

.

Gender

There is a short section on gender differences which points out that, for students with KS2 L5:

- In English there was a 10 percentage point gap in favour of girls at Grade B and above and an 11 point gap in favour of girls at A*/A.

- In maths there was a five percentage point gap at both Grade B and above and Grade A*/A.

But the interrelationship with excellence gaps and the size of the high attainer population is not explored.

.

Progression to competitive higher education

The Executive Summary mentions one outcome from the 2012/13 destinations data – that only 5% of disadvantaged students completing KS5 in 2012 progressed to ‘the top universities’. (The main text also compares the progression rates for state-funded and independent schools).

It acknowledges some improvement compared with previous years, but notes the disparity with progression rates for students from comparatively advantaged backgrounds.

A subsequent footnote reveals that Ofsted is referring throughout to progression to Russell Group universities

The Executive Summary also highlights regional differences:

‘For example, even within a high-achieving region like London, disadvantaged students in Brent are almost four times as likely to attend a prestigious university as those in Croydon.’

The main text adds:

‘For example, of the 500 or so disadvantaged students in Kent, only 2% go on to attend a top university. In Manchester, this rises to 9%. Disadvantaged students in Barnet are almost four times as likely as their peers in Kent to attend a prestigious university.’

Annex A provides only one statistic concerning progression from KS2 to KS5:

‘One half of students achieving Level 5 in English and mathematics at Key Stage 2 failed to achieve any A or A* grades at A level in non-selective schools’

There is no attempt to relate this data to the other variables discussed above.

.

Ofsted’s Evidence base – inspection and survey evidence

The qualitative evidence in Ofsted’s report is derived from:

- A survey of 40 non-selective secondary schools and 10 primary schools. All the secondary schools had at least 15% of students ‘considered to be high attaining at the end of Key Stage 2’ (as opposed to meeting Ofsted’s definition), as well as 10% or more considered to be low-attaining. The sample varied according to size, type and urban or rural location. Fifteen of the 40 were included in the survey underpinning the original 2013 report. Nine of the 10 primary schools were feeders for the secondaries in the sample. In the secondary schools, inspectors held discussions with senior leaders, as well as those responsible for transition and IAG (so not apparently those with lead responsibility for high attainers). They also interviewed students in KS3 and KS5 and looked at samples of students’ work.

The six survey questions are shown below

.

.

- Supplementary questions asked during 130 Section 5 inspections, focused on how well the most able students are maintaining their progress in KS3, plus challenge and availability of suitable IAG for those in Year 11.

- An online survey of 600 Year 8 and Year 11 students from 17 unidentified secondary schools, plus telephone interviews with five Russell Group admissions tutors.

The Report divides the qualitative dimension of its report into seven sections that map broadly on to the six survey questions.

The summary below is organised thematically, pulling together material from the key findings and supporting commentary. Relevant key findings are emboldened. Some of these have relevance to sections other than that in which they are located.

The length of each section is a good guide to the distribution and relative weight of Ofsted’s qualitative evidence

.

Most able disadvantaged

‘Schools visited were rarely meeting the distinct needs of students who are most able and disadvantaged. Not enough was being done to widen the experience of these students and develop their broader knowledge or social and cultural awareness early on in Key Stage 3. The gap at Key Stage 4 between the progress made by the most able disadvantaged students and their better off peers is still too large and is not closing quickly enough.’

The 2013 Report found few instances of pupil premium being used effectively to support the most able disadvantaged. This time round, about a third of survey schools were doing so. Six schools used the premium effectively to raise attainment.

Funding was more often used for enrichment activities but these were much less common in KS3, where not enough was being done to broaden students’ experience or develop social and cultural awareness.

In less successful schools, funding was not targeted ‘with the most able students in mind’, nor was its impact evaluated with sufficient precision.

In most survey schools, the proportion of most able disadvantaged was small. Consequently leaders did not always consider them.

In the few examples of effective practice, schools provided personalised support plans.

.

.

Leadership

Ofsted complains of complacency. Leaders are satisfied with their most able students making the expected progress – their expectations are not high enough.

School leaders in survey schools:

‘…did not see the need to do anything differently for the most able as a specific group.’

One head commented that specific support would be ‘a bit elitiist’.

In almost half of survey schools, heads were not prioritising the needs of their most able students at a sufficiently early stage.

Just 44 of the 130 schools asked supplementary questions had a senior leader with designated responsibility for the most able. Of these, only 16 also had a designated governor.

The Report comments:

‘This suggests that the performance of the most able students was not a high priority…’

.

Curriculum

‘Too often, the curriculum did not ensure that work was hard enough for the most able students in Key Stage 3. Inspectors found that there were too many times when students repeated learning they had already mastered or did work that was too easy, particularly in foundation subjects.’

Although leaders have generally made positive curriculum changes at KS4 and 5, issues remain at KS3. General consensus amongst students in over half the survey schools was that work is too easy.

Students identified maths and English as more challenging than other subjects in about a third of survey schools.

In the 130 schools asked supplementary questions, leaders rarely prioritised the needs of the most able at KS3. Only seven offered a curriculum designed for different abilities.

In the most effective survey schools the KS3 curriculum was carefully structured:

‘…leaders knew that, for the most able, knowledge and understanding of content was vitally important alongside the development of resilience and knowing how to conduct their own research.’

By comparison, the KS4 curriculum was tailored in almost half of survey schools. All the schools introduced enrichment and extra-curricular opportunities, though few were effectively evaluated.

.

Assessment and tracking

Assessment, performance tracking and target setting for the most able students in Key Stage 4 were generally good, but were not effective enough in Key Stage 3. The schools visited routinely tracked the progress of their older most able students, but this remained weak for younger students. Often, targets set for the most able students were too low, which reflected the low ambitions for these students. Targets did not consistently reflect how quickly the most able students can make progress.’

Heads and assessment leaders considered tracking the progress of the most able sufficient to address their performance, but only rarely was this information used to improve curriculum and teaching strategies.

Monitoring and evaluation tends to be focused on KS4. There were some improvements in tracking at KS4 and KS5, but this had caused many schools to lose focus on tracking from the start of KS3.

KS3 students in most survey schools said their views were sought, but could not always point to changes as a consequence. Only in eight schools were able students’ views sought as a cohort.

Year 8 respondents to the online survey typically said schools could do more to develop their interests.

At KS3, half the survey schools did not track progress in all subjects. Where tracking was comprehensive, progress was inconsistent, especially in foundation subjects.

Assessment and tracking ‘generally lacked urgency and rigour’. This, when combined with ineffective use of KS2 assessments:

‘… has led to an indifferent start to secondary school for many of the most able students in these schools.’

KS2 tests were almost always used to set targets but five schools distrusted these results. Baseline testing was widely used, but only about a quarter of the sample used it effectively to spot gaps in learning or under-achievement.

Twenty-six of the 40 survey schools set targets ‘at just above national expectations’. For many students these were insufficiently demanding.

Expectations were insufficiently high to enable them to reach their potential. Weaknesses at KS3 meant there was too much to catch up at KS4 and 5.

In the better examples:

‘…leaders looked critically at national expectations and made shrewd adjustments so that the most able were aiming for the gold standard of A and A* at GCSE and A levels rather than grade B. They ensured that teachers were clear about expectations and students knew exactly what was expected of them. Leaders in these schools tracked the progress of their most able students closely. Teachers were quickly aware of any dips in performance and alert to opportunities to stretch them.’

The expectations built into levels-based national curriculum assessment imposed ‘a glass ceiling’. It is hoped that reforms such as Progress 8 will help raise schools’ aspirations.

.

Quality of teaching

‘In some schools, teaching for the most able lacked sufficient challenge in Key Stage 3. Teachers did not have high enough expectations and so students made an indifferent start to their secondary education. The quality of students’ work across different subjects was patchy, particularly in foundation subjects. The homework given to the most able was variable in how well it stretched them and school leaders did not routinely check its effectiveness.’

The most common methods of introducing ‘stretch’ reported by teachers and students were extension work, challenge questions and differentiated tasks.

But in only eight of the survey schools did teachers have specific training in applying these techniques to the most able.

As in 2013, teaching at KS3 was insufficiently focused on the most able. The quality of work and tasks set was patchy, especially in foundation subjects. In two-thirds of survey schools work was insufficiently challenging in foundation subjects; in just under half, work was insufficiently challenging in maths and English.

Students experienced a range of teaching quality, even in the same school. Most said there were lessons that did not challenge them. Older students were more content with the quality of stretch and challenge.

In only about one fifth of survey schools was homework adapted to the needs of the most able. Extension tasks were increasingly common.

The same was true of half of the 130 schools asked supplementary questions. Only 14 had a policy of setting more challenging homework for the most able.

Most schools placed students in maths and science sets fairly early in Year 7, but did so less frequently in English.

In many cases, older students were taught successfully in mixed ability classes, often because there were too few students to make sets viable:

‘The fact that these schools were delivering mixed ability classes successfully suggests that the organisation of classes by ability is not the only factor affecting the quality of teaching. Other factors, such as teachers not teaching their main subject or sharing classes or leaders focusing the skills of their best teachers disproportionately on the upper key stages, are also influential.’

.

School culture and ethos

‘Leaders had not embedded an ethos in which academic excellence was championed with sufficient urgency. Students’ learning in Key Stage 3 in the schools visited was too frequently disrupted by low-level disruption, particularly in mixed-ability classes. Teachers had not had enough effective training in using strategies to accelerate the progress of their most able students.’

Where leadership was effective, leaders placed strong emphasis on creating the right ethos. School leaders had not prioritised embedding a positive ethos at KS3 in 22 of the survey schools.

In half of the survey schools, the most able students said their learning was affected by low-level disruption, though teachers in three-quarters of schools maintained this was rare. Senior leaders also had a more positive view than students.

In 16 of the schools, students thought behaviour was less good in mixed ability classes and staff tended to agree.

.

Transition

‘Inspectors found that the secondary schools visited were not using transition information from primary schools effectively to get the most able off to a flying start in Key Stage 3. Leaders rarely put in place bespoke arrangements for the most able students. In just under half of the schools visited, transition arrangements were not good enough. Some leaders and teachers expressed doubt about the accuracy of Key Stage 2 results. The information that schools gathered was more sophisticated, but, in too many cases, teachers did not use it well enough to make sure students were doing work with the right level of difficulty.’

Too often poor transition arrangements meant students were treading water in KS3. The absence of leadership accountability for transition appeared a factor in stifled progress at KS4 and beyond.

Transfer arrangements with primary schools were not well developed in 16 of the survey schools. Compared with 2013, schools were more likely to find out about pupils’ strengths and weaknesses, but the information was rarely used well.

Secondary schools had more frequent and extended contact with primary schools through subject specialists to identify the most able, but these links were not always used effectively. Only one school had a specific curriculum pathway for such students.

Leaders in four of the ten primary schools surveyed doubted whether secondary schools used transition information effectively.

However, transition worked well in half of the secondary schools. Six planned the Year 7 curriculum jointly with primary teachers. Leaders had the highest expectations of their staff to ensure that the most able were working at the appropriate level of challenge.

Transition appeared more effective where schools had fewer feeder primaries. About one third of the sample had more than 30 feeder schools, which posed more difficulties, but four of these schools had effective arrangements.

.

Progression to HE

‘Information, advice and guidance to students about accessing the most appropriate courses and universities were not good enough. There were worrying occasions when schools did too little to encourage the most able students to apply to prestigious universities. The quality of support was too dependent on the skills of individual staff in the schools visited.

While leaders made stronger links with universities to provide disadvantaged students in Key Stages 4 and 5 with a wider range of experiences, they were not evaluating the impact sharply enough. As a result, there was often no way to measure how effectively these links were supporting students in preparing successful applications to the most appropriate courses.’

Support and guidance about university applications is ‘still fragile’ and ‘remains particularly weak’.

Students, especially those from disadvantaged backgrounds, were not getting the IAG they need. Ten survey schools gave no specific support to first generation university attendees or those eligible for the pupil premium.

Forty-nine of the 130 school asked additional questions did not prioritise the needs of such students. However, personalised mentoring was reported in 16 schools.

In four survey schools students were not encouraged to apply to the top universities.

‘The remnants of misplaced ideas about elitism appear to be stubbornly resistant to change in a very small number of schools. One admissions tutor commented: ‘There is confusion (in schools) between excellence and elitism’.

Only a third of survey schools employed dedicated staff to support university applications. Much of the good practice was heavily reliant on the skills of a few individuals. HE admissions staff agreed.

In 13 of the schools visited, students had a limited understanding of the range of opportunities available to them.

Survey schools had a sound understanding of subject requirements for different degree courses. Only about one-quarter engaged early with parents.

.

Ofsted and other Central Government action

‘Ofsted has sharpened its focus on the progress and quality of teaching of the most able students. We routinely comment on the achievement of the most able students in our inspection reports. However, more needs to be done to develop a clearer picture of how well schools use pupil premium funding for their most able students who are disadvantaged and the quality of information, advice and guidance provided for them. Ofsted needs to sharpen its practice in this area.’

The Department for Education has developed useful data about students’ destinations when they leave Key Stage 4. However, information about students’ destinations when they leave Key Stage 5 is not as comprehensive and so is less useful.’

.

Ofsted’s recommendations and conclusions

This is a somewhat better Report than its June 2013 predecessor, although it continues to fall into several of the same statistical and presentational traps.

It too is a curate’s egg.

For any student of effective provision for the most able, the broad assessment in the previous section is profoundly unsurprising, but its endorsement by Ofsted gives it added power and significance.

We should be grateful that HMCI has chosen to champion this issue when so many others are content to ignore it.

The overall message can best be summarised by juxtaposing two short statements from the Report, one expressed positively, another negatively:

- In over half of survey schools, the most able KS3 students were progressing as well as, or better than, others.

- The needs of the most able were not being met effectively in the majority of survey schools.

Reading between the lines, too often, the most able students are succeeding despite their schools, rather than because of them.

What is rather more surprising – and potentially self-defeating – is Ofsted’s insistence on laying the problem almost entirely at the door of schools, and especially of headteachers.

There is most definitely a degree of complacency amongst school leaders about this issue, and Ofsted is quite right to point that out.

The determination of NAHT and ASCL to take offence at the criticism being directed towards headteachers, to use volatility and change as an excuse and to urge greater focus on the pockets of good practice is sufficient evidence of this.

But there is little by way of counterbalance. Too little attention is paid to the question whether the centre is providing the right support – and the right level of support – to facilitate system-wide improvement. It as if the ‘school-led, self-improving’ ideal is already firmly in place.

Then again, any commitment on the part of the headteachers’ associations to tackling the root causes of the problem is sadly lacking. Meanwhile, the teachers;’ associations ignored the Report completely.

Ofsted criticises this complacency and expresses concern that most of its survey schools:

‘…have been slow in taking forward Ofsted’s previous recommendations, particularly at KS3’

There is a call for renewed effort:

‘Urgent action is now required. Leaders must grasp the nettle and radically transform transition from primary school and the delivery of the Key Stage 3 curriculum. Schools must also revolutionise the quality of information, advice and guidance for their most able students.’

Ofsted’s recommendations for action are set out below. Seven are directed at school leaders, three at Ofsted and one at DfE.

.

Those aimed by Ofsted towards itself are helpful in some respects.

For example, there is implicit acknowledgement that, until now, inspectors have been insufficiently focused on the most able from disadvantaged backgrounds.

Ofsted stops short of meeting my call for it to produce guidance to help schools and inspectors to understand Ofsted’s expectations.

But it is possible that it might do so. Shortly after publication of the Report, its Director for Schools made a speech confirming that:

‘… inspectors are developing a most able evaluation toolkit for schools, aligned to that which is in place for free school meals’.

.

.

If Ofsted is prepared to consult experts and practitioners on the content of that toolkit, rather than producing it behind closed doors, it is more likely to be successful.

There are obvious definitional issues stemming from the fact that, according to Ofsted’s current approach, the ‘most able’ population constitutes 40-50% of all learners.

While this helps to ensure relevance to every school, no matter how depressed the attainment of its intake, it also highlights the need for further differentiation of this huge population.

Some of Ofsted’s statistical indicators and benchmarking tools will need sharpening, not least to avoid the pitfalls associated with the inverse relationship between the proportion of high attainers and the proportion of disadvantaged learners.

They might usefully focus explicitly on the distribution and incidence of the disadvantaged most able.

.

Prospects for success

But the obvious question is why schools should be any more likely to respond this time round than in 2013?

Will the references in the Ofsted inspection handbook plus reformed assessment arrangements be sufficient to change schools’ behaviour?

Ofsted is not about to place explicit requirements on the face of the inspection framework.

We are invited to believe that Progress 8 in particular will encourage secondary schools to give due attention to the needs of high attainers.

Yet there is no commitment to the publication of a high attainers’ performance measure (comparable to the equivalent primary measure) or the gap on that measure between those from advantaged and disadvantaged backgrounds.

Data about the performance of secondary high attainers was to have been made available through the now-abandoned Data Portal – and there has been no information about what, if anything, will take its place.

And many believe that the necessary change cannot be achieved by tinkering with the accountability framework.

The specialist organisations are united in one respect: they all believe that schools – and learners themselves – need more direct support if we are to spread current pockets of effective practice throughout the system.

But different bodies have very different views about what form that support should take. Until we can:

- Establish the framework necessary to secure universally high standards across all schools without resorting to national prescription

we – and Ofsted – are whistling in the wind.

.

GP

March 2015

I shall not repeat here previous coverage of how Ofsted’s emphasis on the most able has been framed. Interested readers may wish to refer to previous posts for details:

I shall not repeat here previous coverage of how Ofsted’s emphasis on the most able has been framed. Interested readers may wish to refer to previous posts for details: