.

This post reviews the Sutton Trust’s Research Brief ‘Missing Talent’, setting it in the context of the Trust’s own priorities and the small canon of research on excellence gaps in the English education system.

This post reviews the Sutton Trust’s Research Brief ‘Missing Talent’, setting it in the context of the Trust’s own priorities and the small canon of research on excellence gaps in the English education system.

It is structured as follows:

- Background on what has been published and my own involvement in researching and debating these issues.

- Analysis of the data-driven substance of the Research Brief

- Analysis of the recommendations in the Research and their fit with previous recommendations contained in the Sutton Trust’s Mobility Manifesto (September 2014)

- Commentary on the quality of the Research Brief, prospects for the adoption of these recommendations and comparison with my own preferred way forward.

.

Background

‘Missing Talent’ was prepared for The Sutton Trust by education datalab, an offshoot of the Fischer Family Trust (FFT).

The project was announced by education datalab in March (my emphases):

‘This is a short piece of research to explore differences in the secondary school experiences of highly able children from deprived backgrounds, compared to others. Its purpose is to identify whether and why some of the top 10% highest attaining children at the end of primary school do not achieve their full potential at age 16…

…For this group of highly able children we will:

- describe the range of different GCSE outcomes they achieve

- show their distribution across local authorities and different types of schools

- explore whether there is any evidence that different types of high attaining children need to be differentially catered for within our education system

We hope our research will be able to suggest what number and range of qualifications schools should plan to offer students in this group. We may be able to identify parts of the country or particular types of schools where these students are not currently reaching their potential. We will be able to show whether highly able children from particular backgrounds are not currently reaching their full potential, with tentative suggestions as to whether school or home support are mostly contributing to this underperformance.’

On 2 June 2015, The Sutton Trust published:

- A Research Brief (Number 5) containing the outcomes of this work

- An Overview summarising the key findings and recommendations

- A Press Release ‘Over a third of clever but poor boys significantly underachieve at GCSE’ and

- A guest blog post – Advancing the able – authored by Rebecca Allen, education datalab director. This also appears on the education datalab site.

The post is mostly about the wider issue of the priority attached to support for high attainers. It contains a gratifying reference to ‘brilliant blogger Gifted Phoenix’, but readers can rest assured that I haven’t pulled any punches here as a consequence!

The press release provided the substance of the ensuing media coverage, including pieces by the BBC, Guardian, Mail, Schools Week and TES.

There was limited commentary on social media since release of the Research Brief coincided with publication of the legislation underpinning the new Conservative Government’s drive for academisation. I commented

.

.

Just prior to publication and at extremely short notice I was asked by Schools Week for a comment that foregrounded references to the pupil premium.

This was in their coverage:

“I wholeheartedly support any action to reinforce effective practice in using pupil premium to support ‘the most able disadvantaged’.

“Ofsted is already taking action, but this should also be embedded in pupil premium reviews and become a higher priority for the Education Endowment Foundation.

“Given their close relationship, I hope the Sutton Trust will pursue that course. They might also publicly oppose Teach First proposals for redistributing pupil premium away from high and middle attainers and engage more directly with those of us who are pursuing similar priorities.”

For those who are unaware, I have been campaigning against Teach First’s policy position on the pupil premium, scrutinised in this recent post: Fisking Teach First’s defence of its pupil premium policy (April 2015). This is also mentioned in the Allen blog post.

I have also written extensively about excellence gaps, provisionally defined as:

‘The difference between the percentage of disadvantaged learners who reach a specified age- or stage-related threshold of high achievement – or who secure the requisite progress between two such thresholds – and the percentage of all other eligible learners that do so.’

This appears in a two-part review of the evidence base published in September 2014:

I have drawn briefly on that material in the commentary towards the end of this post.

.

Research Brief findings

.

Main findings, definitions and terminology

The Research Brief reports its key findings thus:

- ‘15% of highly able pupils who score in the top 10% nationally at age 11 fail to achieve in the top 25% at GCSE

- Boys, and particularly pupil premium eligible boys, are most likely to be in this missing talent group

- Highly able pupil premium pupils achieve half a grade less than other highly able pupils, on average, with a very long tail to underachievement

- Highly able pupil premium pupils are less likely to be taking GCSEs in history, geography, triple sciences or a language’

These are repeated verbatim in the Trust’s overview of research, but are treated slightly differently in the press release, which foregrounds the performance of boys from disadvantaged backgrounds:

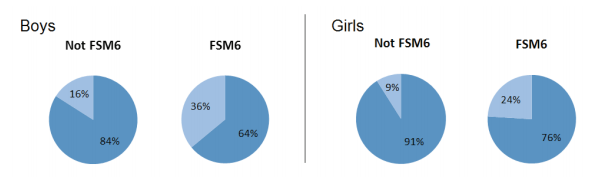

‘Over a third (36%) of bright but disadvantaged boys seriously underachieve at age 16, new Sutton Trust research reveals today. Clever but poor girls are slightly less likely to underperform, with just under a quarter (24%) getting disappointing GCSE results. These figures compare with 16% of boys and 9% of girls from better off homes who similarly fall behind by age 16.’

The opening paragraph of the Brief describes ‘highly able’ learners as those achieving within the top decile in KS2 tests. This is a measure of prior attainment, not a measure of ability and it would have been better if the document referred to high attainers throughout.

There is also a curious and cryptic reference to this terminology

‘…following Sutton Trust’s previously used notion of those ‘capable of excellence in school subjects’’

which is not further explained (though ‘capable’ implies a measure of ability rather than attainment).

The analysis is based on the 2014 GCSE cohort and is derived from ‘their mark on each KS2 test paper they sat in 2009’. It therefore depends on high average performance across statutory tests of English, maths and (presumably) science.

The single measure of GCSE performance is achievement on the Attainment 8 measure, as defined in 2014. This has not been made available through the 2014 Secondary Performance Tables.

Essentially Attainment 8 comprises English and maths (both double-weighted) any three EBacc subjects and three other approved qualifications (the Brief says they must be GCSEs).

The measure of ‘missing talent’ is derived from the relationship between these two performance measures. It comprises those who fall within the top decile at KS2 but outside the top quartile nationally (ie the top 25%) at KS4.

There is no explanation or justification for the selection of these two measures, why they are pitched differently and why the difference between them has been set at 15 percentage points.

The text explains that some 7,000 learners qualify as ‘missing talent’, about 15% of all highly able learners (so the total of all highly able learners must approach 47,000).

The analysis is based on certain presumptions about consistency of progress between key stages. The brief says, rather dismissively:

‘Progress through school is not always smooth and predictable. Of course some children do well at primary school but are overtaken by peers who thrive at secondary school.’

It does not mention education datalab’s own analysis which shows that only 45% of learners make the expected linear progress between KS2 and KS3 and just 33% do so between KS3 and KS4. It would have been interesting and useful to have seen material about inconsistency of progress amongst this cohort.

Presumably the selection of top decile at KS2 but top quartile at KS4 is intended in part to compensate for this effect.

The main body of the Research Brief provides analysis of four topics:

- The characteristics of the ‘missing talent’ subset – covering gender, ethnic background and socio-economic disadvantage.

- Performance on the Attainment 8 measure of ‘missing talent’ from disadvantaged backgrounds compared with their more advantaged peers.

- Take up of EBacc subjects by this population, including triple science.

- The geographical distribution of ‘missing talent’ between local authorities and schools.

The sections below deal with each of these in turn.

.

The characteristics of ‘missing talent’

The ‘missing talent’ population comprises some 7,000 learners, so about 1 in 7 of all highly able learners according to the definition deployed.

We are not provided with any substantive information about the characteristics of the total highly able cohort, so are unable to quantify the differences between the composition of that and the ‘missing talent’ subset.

However we are told that the ‘missing talent’ group:

- Is slightly more likely to be White British, Black Caribbean, Pakistani or Bangladeshi and somewhat less likely to be Chinese, Indian or African.

- Includes 1,557 learners (943 boys and 614 girls) who are disadvantaged. The measure of disadvantage is ‘ever 6 FSM’ the basis for the receipt of pupil premium on grounds of deprivation. This is approximately 22% of the ‘missing talent’ group.

- Includes 24% of the ‘ever 6 FSM’ girls within the highly able cohort compared with 9% of others; and includes 36% of ‘ever 6 FSM’ boys within the whole cohort compared with 16% of others.

Hence: ‘ever 6 FSM’ learners of both genders are more likely to be part of ‘missing talent’; boys are more likely than girls to be included, regardless of socio-economic status; and ‘ever 6 FSM boys are significantly more likely to be included than ‘ever 6 FSM’ girls.

.

.

The fact that 36% of ‘ever 6 FSM’ boys fall within the ‘missing talent’ group is described as ‘staggering’.

By marrying the numbers given with the percentages in the charts above, it seems that some 5,180 of the total highly able population are disadvantaged – roughly 11% – so both disadvantaged boys and girls are heavily over-represented in the ‘missing talent’ subset (some 30% of the total disadvantaged population are ‘missing talent’) and significantly under-represented in the total ‘highly able’ cohort.

By comparison, the 2014 Secondary Performance Tables show that 26.9% of the overall 2014 GCSE cohort in state-funded schools are disadvantaged (though this includes children in care).

There is no analysis to show whether there is a particular problem with white working class boys (or any other sub-groups for that matter) although that might be expected.

.

Attainment 8 performance

Attainment 8 is described as ‘the Government’s preferred measure’, although we anticipate that proposals in the Conservative manifesto for a ‘compulsory EBacc’ will almost certainly change its nature significantly, even if it is not supplanted by the EBacc.

The document supplies a table showing the average grade (points equivalents) for different percentiles of the ‘highly able FSM6’, ‘highly able not FSM6’ and ‘not highly able’ populations.

.

.

Median (50th percentile) performance for ‘highly able FSM6’ is 6.7, compared with 7.2 for ‘highly able not FSM6’ and 5.0 for ‘not highly able’.

The commentary translates this:

‘…they [‘highly able FSM 6’] score 4As and 4Bs when their equally able classmates from better off backgrounds get straight As’.

By analogy, the ‘not highly able’ group are achieving straight Cs.

However, there is also a ‘long tail of underachievement’ amongst the highly able disadvantaged:

‘One in ten of the poor but clever pupils are barely achieving C grades (or doing much worse) and at this end of the distribution they are lagging their non-FSM6 peers by almost a whole GCSE grade per subject.’

The latter is actually only true at the 95th percentile.

By comparison, at that point in the distribution, the ‘not highly able’ population are achieving 8 F grades.

So there is a clear excellence gap between the Attainment 8 performance of the highly able and the highly able disadvantaged, though the difference only becomes severe at the extreme of the distribution – the reference to a ‘long tail’ is perhaps a little overdone.

.

Take-up of EBacc subjects

A second table shows the distribution of grades for ‘highly able FSM6’ and ‘highly able not FSM6’ across the five EBacc components: English, maths, sciences, humanities and languages.

.

.

This is not discussed extensively in the text, but it reveals some interesting comparisons. For example, the percentage point excellence gaps between the two populations at GCSE grades A*/A are: maths 17 points; English 16 points; sciences 22 points; humanities 21 points; and languages 18 points.

At the other extreme 23% of ‘highly able FSM6’ are Ungraded in languages, as are 16% in humanities. This is particularly worrying if true, but Ungraded almost certainly includes those not entered for an appropriate examination.

The commentary says that ‘almost a quarter will not be taking a language at GCSE’, which might suggest that U is a misnomer. It is not clear whether the U category includes both non-takers and ungraded results, however.

The Government’s plans for ‘compulsory EBacc’ seem likely to force all learners to take a language and history or geography in future.

They will be less likely to make triple science compulsory for high attainers, though this is deemed significant in the document:

‘Just 53% of the highly able FSM6 pupils take triple sciences, compared to 69% of those not in the FSM6 category. This may be through choice or because they are in one of the 20% of schools that does not offer the curriculum. Here again the differences are stark: 20% of highly able FSM6 pupils are in a school not offering triple sciences, compared to just 12% of the highly able not-FSM6 pupils.’

The EBacc does not itself require triple sciences. The implications for teacher supply and recruitment of extending them into the schools that do not currently offer them are not discussed.

.

Geographical distribution of ‘missing talent’

At local authority level the Brief provides a list of 20 areas with relatively high ‘missing talent’ and 20 areas at the other extreme.

The bulk of the former are described as areas where secondary pupil performance is low across the attainment spectrum, but four – Coventry, Lambeth, Leicester and Tower Hamlets – are good overall, so the underachievement of high attainers is apparently exceptional.

Some are described as having comparatively low populations of highly able learners but, as the text implies, that should not be an excuse for underachievement amongst this cohort.

It is not clear whether there is differential performance in respect of disadvantaged learners within the ‘missing talent’ group (though the sample sizes may have been too low to establish this).

It is, however, immediately noticeable that the list of areas with high ‘missing talent’ includes many of the most disadvantaged authorities, while the list with low levels of missing talent is much more ‘leafy’.

Most of the former are located in the Midlands or the North. Almost all were Excellence in Cities areas.

The ‘low missing talent’ list also includes 11 London boroughs, but there are only three on the ‘high missing talent’ list.

The Brief argues that schools with low levels of ‘missing talent’ might support others to improve. It proposes additional selection criteria including:

- ‘A reasonable number of highly able pupils’ – the rather arbitrary cut-off specified is 7% of cohort. It is not clear whether this is the total cohort or only the GCSE cohort. If the latter, it is more than likely to vary from year to year.

- ‘Relatively low levels of missing talent’ – fewer than 10% ‘significantly underperform’. It is not clear but one assumes that the sole measure is that described above (ie not within the top 25% on the Attainment 8 measure).

- ‘A socially mixed intake’ with over 10% of FSM6 learners (this is very low indeed compared with the average for the 2014 GCSE cohort in state-funded schools of 26.9%. It suggests that most of the schools will have relatively advantaged intakes.)

- Triple science must be offered and the schools must have ‘a positive Progress 8 score overall’ (presumably so that they perform reasonably well across the attainment spectrum).

There is no requirement for the school to have achieved a particular Ofsted rating at its most recent inspection.

We are told that there are some 300 schools meeting this description, but no details are given about their distribution between authorities and regions, beyond the fact that:

‘In half of the 20 local authorities with the highest levels of missing talent there is no exemplar school and so a different policy approach may have to be taken.’

This final section of the document becomes a little discursive, stating that:

‘Any new initiatives to support highly able children at risk of falling behind must recognise the successes and failures of past ‘Gifted and Talented’ initiatives, particularly those of the Blair and Brown governments.’

And

‘We believe that any programme of support – whether through the curriculum or through enrichment – must support schools and children in their localities.’

No effort is made to identify these successes and failures, or to provide evidence to substantiate the belief in localised support (or to explain exactly what that means).

.

Recommendations

.

In the Research Brief

The Research Brief itself consists largely of data analysis, but proffers a brief summary of key findings and a set of policy recommendations.

It is not clear whether these emanate from the authors of the research or have been superimposed by the Trust, but the content distinctly suggests the latter.

There are four recommendations (my emphases):

- ‘The Government should implement the recommendations of Sutton Trust’s Mobility Manifesto to develop an effective national programme for highly able state school pupils, with ring-fenced funding to support evidence-based activities and tracking of pupils’ progress.

- All schools must be made accountable for the progress of their most able pupils. These pupils should have access to triple sciences and must study a broad traditional curriculum, including a language and humanity, that widens their future educational opportunities. The Government should report the (3-year average) Progress 8 figures for highly able pupils in performance tables. Schools where highly able pupils currently underperform should be supported through the designation of another local exemplar school. In the small number of areas where there is no exemplary good practice, a one-off centralised support mechanism needs to be set-up.

- Exemplar schools already successfully catering for highly able pupils that are located in areas of high missing talent should be invited to consider whether they are able to deliver a programme of extra-curricular support to raise horizons and aspirations for children living in the wider area.

- Highly able pupils who receive Pupil Premium funding are at high risk of underperforming at age 16. Schools should be encouraged to use the Pupil Premium funding for these pupils to improve the support they are able to give them.’

These are also repeated unchanged in the research overview, but are summarised and rephrased slightly in the press release.

Instead of demanding ‘an effective national programme…with ring-fenced funding to support evidence-based activities and tracking of pupils’ progress’ this calls on the Government to:

‘…establish a new highly able fund to test the most effective ways of improving the progress and attainment of highly able students in comprehensive schools and to show that the needs of highly able students, especially those from low and middle income backgrounds, are placed high on the national policy agenda.’

This is heavily redolent of Labour’s pre-election commitment to introduce a Gifted and Talented Fund which would establish a new evidence base and help schools’ ‘work in stretching the most able pupils’.

My own analysis of Labour’s commitment (March 2015) drew attention to similarities between this and The Sutton Trust’s own Mobility Manifesto (September 2014).

.

In the Mobility Manifesto

The Manifesto is mentioned in the footnotes to the press release. It offers three recommendations pertaining to highly able learners:

- ‘Reintroduce ring-fenced government funding to support the most able learners (roughly the top ten per cent) in maintained schools and academies from key stage three upwards. This funding could go further if schools were required to provide some level of match funding.

- Develop an evidence base of effective approaches for highly able pupils and ensure training and development for teachers on how to challenge their most able pupils most effectively.

- Make a concerted effort to lever in additional support from universities and other partners with expertise in catering for the brightest pupils, including through creating a national programme for highly able learners, delivered through a network of universities and accessible to every state-funded secondary school serving areas of disadvantage.’

The press release also mentions the Trust’s Sutton Scholars Scheme, a pilot programme undertaken with partner universities that supports highly able learners from low and middle income backgrounds during KS3.

In 2013 there was an initial pilot with 100 pupils involving UCL. In 2014 this was extended to 400 pupils and four partner universities: UCL, Cambridge, Nottingham and Warwick.

The press release says it currently reaches 500 pupils but still involving just four universities, so this is presumably the size of the 2015 cohort.

The programmes at each institution are subtly different but all involve a mix of out-of-school activities. In most cases they appear to be rebadging elements of the universities’ existing outreach programmes; there is nothing startlingly innovative or radical about them.

.

Commentary

.

Quality of the Research Brief

The document is compressed into three sides of A4 so, inevitably, much valuable information is missing. Education datalab should consider making available a separate annex containing all the underlying data that can be released without infringing data protection rules.

The Brief does not address all the elements set out in the original project description. It does not show the distribution of high attainers by type of school, or discuss the impact on underperformance of home and school respectively, nor does it:

‘…explore whether there is any evidence that different types of high attaining children need to be differentially catered for within our education system’.

It seems that the project has been scaled back compared with these original intentions, whether for lack of useful data or some other reason.

When it comes to the findings that are included:

- The general conclusions about underachievement, particularly amongst high attainers from disadvantaged backgrounds, add something to our understanding of achievement patterns and the nature of excellence gaps. But the treatment also begs several questions that remain unanswered. The discussion needs reconciling with education datalab’s own findings about the limited incidence of linear progress. Further analysis of the performance of high-attaining disadvantaged boys may be a particular priority.

- The findings on the take-up of EBacc subjects are relatively unsurprising and second order by comparison. They ought really to have been set in the context of the new Government’s commitment to a ‘compulsory EBacc’ (see below).

- The information about the distribution of ‘missing talent’ is compromised by the very limited analysis, especially of the distribution between schools. The criteria used to identify a subset of 300 exemplar schools do not bear close scrutiny.

There is no cross-referencing to the existing evidence base on excellence gaps, especially the material relating to whether disadvantaged high attainers remain so in ‘The Characteristics of High Attainers’ (DfES 2007), ‘Performing against the odds: developmental trajectories of children in the EPPSE 3-16 study’ (Siraj-Blatchford et al, 2011) and ‘Progress made by high-attaining children from disadvantaged backgrounds’ (Crawford et al 2014).

.

Prospects for the adoption of these recommendations

The recommendation that schools are more strongly encouraged to use the pupil premium to benefit these learners – and to do so effectively – is important, but the text should explain how this can be achieved.

Ofsted has already made the case for action, concluding in March 2015 that two-thirds of non-selective secondary schools are not yet using pupil premium effectively to support disadvantaged high attainers.

Ofsted is committed to ensuring that school inspections focus sharply on the progress of disadvantaged high attainers and that future thematic surveys investigate the effective use of pupil premium to support them.

It is also preparing a ‘most able’ evaluation toolkit that will address this issue. This might provide a basis for further guidance and professional development, as long as the material is high quality and sufficiently detailed.

Effective provision for high attainers should be a higher priority for the pupil premium champion and, as I have already suggested, should feature prominently and explicitly in the guidance supporting pupil premium reviews.

Above all, the EEF should be supporting research on this topic as part of a wider initiative to help schools close excellence gaps.

All parties, including the Government, should make clear their opposition to the policy of Teach First and its Fair Education Alliance to double-weight pupil premium for low attainers at the expense of high and middle attaining recipients.

If at all possible, Teach First should be persuaded to withdraw this misguided policy.

It seems highly probable that the Trust’s recommendation for access to ‘a broad traditional curriculum’ will be secured in part through the new Government’s commitment to make EBacc subjects compulsory.

This is likely to be justified on grounds of social justice, derived from the conviction that taking these subjects supports progression to post-16 education, employment and higher education.

But that notion is contested. When the Education Select Committee considered this issue they concluded (my emphasis):

‘We support the Government’s desire to have greater equality of opportunity for all students, and to improve the attainment of those eligible for free school meals. The evidence is unclear as to whether entering more disadvantaged students for EBac subjects would necessarily make a significant contribution to this aim. Concentrating on the subjects most valued for progression to higher education could mean schools improve the attainment and prospects of their lowest-performing students, who are disproportionately the poorest as well. However, other evidence suggests that the EBac might lead to a greater focus on those students on the borderline of achieving it, and therefore have a negative impact on the most vulnerable or disadvantaged young people, who could receive less attention as a result. At the same time, we believe that the EBac’s level of prescription does not adequately reflect the differences of interest or ability between individual young people, and risks the very shoe-horning of pupils into inappropriate courses about which one education minister has expressed concerns. Given these concerns, it is essential that the Government confirms how it will monitor the attainment of children on free school meals in the EBac.’

This policy will not secure universal access to triple science, though it seems likely that the Government will continue to support that in parallel.

In the final days of the Coalition government, a parliamentary answer said that:

‘Out of 3,910 mainstream secondary schools in England with at least one pupil at the end of key stage four, 2,736 schools entered at least one pupil for triple science GCSEs in 2013/14. This figure does not include schools which offered triple science GCSEs, but did not enter any pupils for these qualifications in 2013/14. It also excludes those schools with no pupils entered for triple science GCSEs but where pupils have been entered for all three of GCSE science, GCSE further science and GCSE further additional science, which together cover the same content as GCSE triple science.

The Government is providing £2.6 million in funding for the Triple Science Support Programme over the period 2014-16. This will give state funded schools with low take up of triple science practical support and guidance on providing triple science at GCSE. The support comprises professional development for teachers, setting up networks of schools to share good practice and advice on how to overcome barriers to offering triple science such as timetabling and lack of specialist teachers.’

The Conservative manifesto said:

‘We aim to make Britain the best place in the world to study maths, science and engineering, measured by improved performance in the PISA league tables…We will make sure that all students are pushed to achieve their potential and create more opportunities to stretch the most able.’

Continued emphasis on triple science seems highly likely, although this will contribute to wider pressures on teacher supply and recruitment.

The recommendation for an additional accountability measure is sound. There is after all a high attainer measure within the primary headline package, though it has not yet been defined beyond:

‘x% of pupils achieve a very high score in their age 11 assessments’.

In its response to consultation on secondary accountability arrangements, the previous government argued that high attainment would feature in the now defunct Data Portal intended to support the performance tables.

It will be important to ensure consistency between primary and secondary measures. The primary measure seems to be based on attainment rather than progress. The Sutton Trust seems convinced that the secondary equivalent should be a progress measure (Progress 8) but does not offer any justification for this.

It is also critical that the selected measures are reported separately for disadvantaged and all other learners, so that the size of the excellence gap is explicit.

.

Prospects for a new national programme

When it comes to the recommendation for a new national programme, the Trust needs to be clearer and more explicit about the fundamental design features.

The recommendations in the Mobility Manifesto and this latest publication are not fully consistent. No effort is made to cost these proposals, to identify the budgets that will support them, or to make connections with the Government’s wider education policy.

Piecing the two sets of recommendations together, it appears that:

- The programme would cater exclusively for the top decile of high attainers in the state-funded secondary sector. Post-16 institutions and selective schools may or may not be included.

- Participation would be determined entirely on the basis of KS2 test outcomes, but it is not clear whether learners would remain within the programme regardless of subsequent progress.

- The programme would comprise two parallel arms – one providing support directly for learners, the other improving the quality of provision for them within their schools and colleges.

- The support for learners is not defined, but would presumably draw on existing Trust programmes. It would include ‘extra-curricular support to raise horizons and aspirations’.

- It is not entirely clear whether this support would be available exclusively to those from disadvantaged backgrounds (though we know it would be ‘accessible to every state-funded secondary school serving areas of disadvantage’).

- The support for schools and colleges will develop and test effective practice in teaching these learners, in tracking and maximising their attainment and progress. It will provide associated professional development. It is not clear whether this will extend into other dimensions of effective whole school provision.

- Delivery will be via some combination of a network of universities, a cadre of exemplar schools and other partners with expertise. The interaction between these different providers is not discussed.

- The exemplar schools will be designated as such and will support other schools in their locality where high attainers under-achieve. They should also be ‘invited to consider’ delivering a programme of extra-curricular support for learners in their area.

- There will also be an unspecified ‘one-off centralised support mechanism’ for areas with no exemplary schools. What this means is a mystery.

- Costs will be met from a new ring-fenced ‘highly able fund’ the size of which is not quantified.

The relationship between this programme and the Trust’s proposed ‘Open Access Scheme’ – which would place high attaining students in independent schools – is not discussed. (I will not repeat again my arguments against this Scheme.)

The realistic prospect of securing a sufficiently large ring-fenced pot must be negligible in the present funding environment. Labour’s pre-election commitment to find some £15m (annually?) for this purpose is unlikely to be matched by the Conservatives.

Any support for improving the quality of provision in schools is likely to be found within existing budgets, including those supporting research, professional development, teaching schools, their alliances and their designated Specialist Leaders of Education.

STEM-related initiatives are particularly relevant given the Manifesto reference. One would hope for a systematic and co-ordinated approach rather than the piecemeal introduction of new projects.

I have elsewhere suggested a set of priorities including:

- Guidance and associated professional development on effective whole school provision derived from a set of core principles, including the adoption of flexible, radical and innovative grouping arrangements.

- Developing a coherent strategy for strengthening the STEM talent pipeline which harnesses the existing infrastructure and makes high quality support accessible to all learners regardless of the schools and colleges they attend.

- Establishing centres of excellence and a stronger cadre of expert teachers, but also fostering system-wide partnership and collaboration by including the range of expertise available outside schools.

If funding is to go towards improving provision for learners, the only viable option is to use pupil premium, with the consequence that support will be targeted principally, if not exclusively, at disadvantaged high attainers.

I have elsewhere suggested a programme designed to support all such learners aged 11-18 located in state-funded schools and colleges. There is both wider reach and less deadweight if support is targeted at all eligible learners, rather than at schools ‘serving areas of disadvantage’.

It is critical to include the post-16 sector, given the significant proportion of disadvantaged high attainers who transfer post-GCSE.

This would be funded principally by a £50m topslice from the pupil premium budget (matching the topslice taken to support Y6/7 summer schools), though higher education outreach budgets would also contribute and there would be scope to attract additional philanthropic support.

The over-riding priority is to bring much-needed coherence to what is currently a fragmented market, enabling:

- Learners to undertake a long-term support programme, tailored to their needs and drawing on the vast range of services offered by a variety of different providers, including universities, commercial and third sector organisations (such as the Trust itself).

- These providers to position and market their services within a single online national prospectus, enabling them to identify gaps on the supply side and take action to fill them.

- A single, unified, system-wide effort, harmonising the ‘pull’ from higher education fair access strategies and the ‘push’ from schools’ and colleges’ work to close excellence gaps.

I don’t yet recognise this coherence in the Trust’s preferred model.

.

GP

June 2015