.

The Conservative Manifesto contained an apparent commitment to a compulsory EBacc:

The Conservative Manifesto contained an apparent commitment to a compulsory EBacc:

‘We will require secondary school pupils to take GCSEs in English, maths, science, a language and history or geography, with Ofsted unable to award its highest ratings to schools that refuse to teach these core subjects.’

We know the commitment will be honoured since, immediately after the election, Prime Minister Cameron confirmed to his Cabinet that he would be implementing the Manifesto in full.

But, while we await clarification in an impending schools white paper, we are somewhat less sure how to interpret the commitment.

.

Origins

The policy first emerged in a newspaper interview with Secretary of State Morgan published at the end of August 2014, some six weeks after her appointment.

This said that:

- State schools would be ‘urged to enrol all pupils for GCSEs in English, maths, science, a language and history or geography…which together form the new “English Baccalaureate”’ and

- Ofsted inspectors would be unable to award a ‘good’ or ‘outstanding’ rating unless a secondary school enrolled all its pupils in the EBacc.

The rationale is to counter educational inequality:

‘“We want students to be able to keep their options open for as long as possible in terms of what they are going to do after school or college,” Mrs Morgan said.

“In selective schools or schools with a low proportion of free school meals, that is what they are already doing. But that is not always happening in less advantaged areas.”’

It may also be seen as reasserting the status of the EBacc as an accountability measure following the introduction of Attainment/Progress 8.

Former Secretary of State Gove initially claimed:

‘That measure will incentivise schools to offer a broad, balanced curriculum, with high-quality teaching and high achievement across the board. It will also affirm the importance of every child enjoying the opportunity to pursue English baccalaureate subjects.’

But the second sentence applies only up to a point – it should properly be qualified by the insertion of ‘some’ before the last three words.

Despite the unequivocal use of the phrase ‘all pupils’, there was already discussion last summer whether this was the Conservatives’ true intention.

.

Manifesto

The wording of the manifesto commitment is slightly different and somewhat vaguer than the original version. It suggests:

- A requirement placed on pupils rather than on schools.

- This requirement now relates to ‘pupils’ rather than ‘all pupils’.

- It also relates to the subjects that constitute the EBacc, but not explicitly to the EBacc itself.

- The restriction on the award of the highest inspection ratings is not tied explicitly to both ‘outstanding’ and ‘good’ (through the phrasing continues to imply this).

- The restriction is confined to schools that ‘refuse to teach’ the EBacc subjects, rather than those that refuse to enter (all) pupils

.

Data

The 2014 Secondary Performance Tables show that only five state-funded secondary schools – all of them selective – entered 100% of their KS4 examination cohort for all EBacc subjects last year (though plenty more selective schools were not far behind them).

The average entry rate across all state-funded schools was 38.7%, but this masks significant variation according to prior attainment.

While some 68.8% of high attainers entered all EBacc subjects, only 31.5% of middle attainers and just 4.0% of low attainers did so.

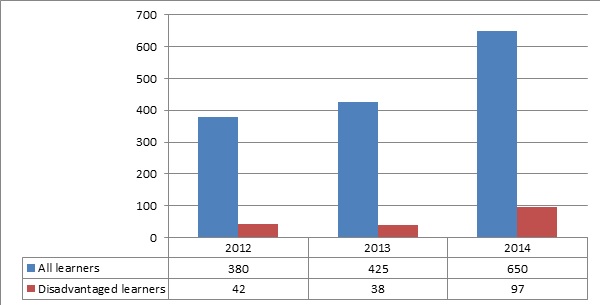

In 2014, 22.9% of disadvantaged pupils entered all EBacc subjects, compared with 44.5% of others, giving a gap of 21.6 percentage points. In 2013 the corresponding gap was 21.5 percentage points and in 2012 17.5 percentage points.

In 2014 only 26 state-funded secondary schools entered no pupils at all for all EBacc subjects, ironically several of them also selective schools, presumably because they use at least one IGCSE examination that is ineligible for inclusion.

Entry rates for different subjects varied considerably. Unsurprisingly maths (97.7%) and English (96.1%) were almost universal, but the languages entry rate stood at 68.9%, just ahead of science at 68.7% with humanities bringing up the rear at 66.5%.

.

Interpretation

Given that the policy is now several months old one would expect much of the detail to have been worked through by Tory policy staff pre-election. DfE officials will also have undertaken some preparatory analysis during purdah. Those two perspectives will now need stitching together.

The obvious point to draw from the data is that, whereas a requirement on schools to enter some pupils for all EBacc subjects would have almost zero impact, insistence that all schools entered all of their pupils would demand huge change.

It would be particularly challenging for schools to apply such a stricture to their low attainers and this would stand in the way of establishing a level playing field between advantaged and disadvantaged students.

Common sense dictates that the policy should be applied in such a way that it falls between these two extremes.

Since the EBacc is currently pegged at GCSE grade C or above, it seems unnecessary and unwise to apply the rule to students who are certain not to achieve this, including many with special needs. Such a requirement would otherwise reinforce failure and damage self-esteem.

The most likely solution would be to introduce a default presumption that all schools should enter all their pupils for all EBacc subjects, with opt-outs acceptable in a limited range of circumstances, or possibly left to the discretion of the headteacher.

An alternative approach might be to remove the C grade hurdle, especially in the case of science, humanities and languages.

.

Other issues

It is hard to see how a requirement could be placed on pupils, unless it is to be applied to their parents, but that seems unnecessarily convoluted and potentially controversial.

One would expect any requirement to be placed on schools, if indeed a requirement is necessary, over and above the disincentive of a restricted inspection outcome.

If that lever is applied to both ‘good’ and ‘outstanding’ judgements it will have a significantly wider reach than if it relates solely to ‘outstanding’ judgements.

Schools might live with a restriction on ‘outstanding’, but if ‘good’ is also restricted that creates a much lower ceiling for some schools and means others have much further to fall.

Given the relatively greater scrutiny afforded to schools requiring improvement it seems likely that few would be prepared to pay such a price.

Faced with such a choice, how many grammar schools would continue to select IGCSE qualifications that do not qualify for the EBacc? (Or would the Government be prepared to relax those rules, which are seen as unduly inflexible?)

Ultimately though, it is not clear whether choosing an ineligible IGCSE would qualify as refusing to teach the EBacc subjects.

It may be that a limiting judgement on Ofsted inspection outcomes would be reserved for the unlikely scenario where schools fail to include these subjects in their KS4 curriculum, or where they wilfully disregard a qualified presumption of EBacc entry.

Some of the difficulties disappear if the presumption is applied only to the subjects that constitute the EBacc and not to the EBacc itself.

This would also remove the C grade hurdle and other complexities could be avoided, including those that extend the EBacc’s reach beyond five subject slots:

- To secure the English element of EBacc requires either an A*-C pass in English or an A*-C pass in English Language and any grade in English Literature.

- To secure the science element of EBacc requires an A*-C pass in core and additional science, or in the science double award, or entry to three separate sciences (choosing from physics, chemistry, biology and computer science) achieving A*-C passes in two of them.

.

Accountability

A further difficulty is presented by the problematic relationship with the Attainment/Progress 8 accountability measures. These are scheduled for introduction in 2016, though schools can opt in this year.

The latest guidelines define the components as:

- A double weighted maths element based on the student’s EBacc maths qualification.

- An English element based on the student’s EBacc English Language or English Literature qualification. This will be double weighted if they have taken both and from 2016 an English (combined) qualification will count and be double weighted.

- Any three further EBacc qualifications. These can be in any combination – all in sciences for example – since there is no requirement to include qualifications in each ‘pillar’ of the EBacc.

- Any further three subjects, including any not counted in any of the sections above. These may be EBacc qualifications, other GCSEs or other approved non-GCSE qualifications.

Compared with this, an EBacc requirement is narrower and more prescriptive since it demands universal study of specific subject combinations beyond the core of English and maths, potentially involving as many as eight qualifications.

There will be five headline performance measures for secondary schools, including Attainment 8, Progress 8 and the percentage of pupils achieving the EBacc. It had become understood that Attainment/Progress 8 were the most significant of these.

The Floor Standard will be tied to Progress 8 giving it higher status than the EBacc for school improvement purposes.

Moreover:

‘Schools in which pupils make one grade more progress than the national average will be exempt from routine inspections by Ofsted in the next academic year.’

If a ‘compulsory’ EBacc and the existing Attainment/Progress 8 are to co-exist, schools will face difficult decisions when students choose their options towards the end of Year 9.

Is it in the best interests of students to enter them for all the EBacc elements, confining curriculum flexibility to the margins, or to exploit to the full the increased flexibility permitted by Attainment/Progress 8?

Assuming that the limiting judgements on Ofsted inspection apply in their strictest sense, should schools prioritise their Ofsted rating or the floor target?

Above all, should the needs of the school – in the shape of its institutional reputation – inevitably trump those of the students, or vice versa?

The Government will need to unravel some of these difficulties.

.

Pressures

The Government will face determined pressure to retain the additional flexibilities guaranteed by Attainment/Progress 8.

Any attempt to restore the EBacc’s supremacy will be regarded as increasing prescription and limiting schools’ autonomy to respond to the different needs of their learners.

It will impose a de facto national curriculum on schools that are not obliged to follow one.

NAHT has signalled already some of the negative reaction that the Government can expect.

Questions have also been raised about the potential teacher recruitment and supply issues associated with reintroducing a compulsory language at KS4 and the limited availability of alternatives for students who would struggle with GCSE.

Another blogger has calculated that 100% take-up of geography, history and languages would require some 7,000 additional teachers, further compounding an already-significant teacher supply problem.

[Postscript: A report in Schools Week on 19 June said that extending MFL to all learners in KS4 had been estimated by education datalab to require ‘well over 2,000’ additional teachers.

Education datalab director Rebecca Allen is quoted:

‘With 30,000 people graduating each year with a degree in languages this isn’t an impossible ask, but is pretty close.’]

There is a corresponding downside for subjects outside the EBacc – RE and arts subjects spring to mind – which had seen Attainment/Progress 8 as a potential route back to higher status.

The notion of introducing new ‘limiting judgements’ on Ofsted inspection ratings is much disliked and may not find favour with HMCI, who is about to publish a single inspection framework and revised handbooks for inspection.

It will be difficult and embarrassing to justify a Government U-turn on educational grounds, especially since both Coalition partners signed up to the previous position.

[Postscript: A post published by SSAT on 10 June, three weeks after this one, compares the language of the Progress 8 guidance – which celebrates its capacity to accommodate the very different needs of learners – with the prescription apparently imposed by the statement in the Conservative manifesto.]

It might just be feasible for a new Government to brazen this out, especially while the Opposition is in disarray, but only at the cost of goodwill amongst the profession and some early reputational damage.

.

.

Likely outcome?

It seems likely that the Government will conclude that a ‘compulsory’ EBacc and Attainment/Progress 8 in its present form simply cannot co-exist.

If so, the path of least resistance is probably to amend Attainment/Progress 8 so that the EBacc subject combination (if not the EBacc in its entirety) sits neatly within it.

The third component above would need to change to require coverage of science, a language and either history or geography.

The fourth component would need to accommodate any further requirements if the full EBacc is subsumed, rather than simply the subject combination.

The limiting judgements applied to Ofsted inspection outcomes should be reserved for schools that fail to offer these subjects at KS4, or possibly extend to those that choose deliberately to ignore a sensible and qualified EBacc presumption. The IGCSE issue needs to be addressed in parallel.

The Government might portray the present Attainment/Progress 8 formulation as a step too far, imposed on them by their Liberal partners in Coalition. They might continue to argue that it is not in the best interests of learners from disadvantaged backgrounds, hindering their efforts to compete on a level playing field for post-16 learning and employment opportunities.

But even such a limited volte-face has presentational downside that will require very careful handling.

One would expect it to trigger the Workload Challenge Protocol on changes to accountability, curriculum and qualifications which stipulates that:

‘There should be a lead in time of at least a year for any accountability, curriculum or qualifications initiative coming from the department which requires schools to make significant changes which will have an impact on staff workload.’

This would necessitate confirmation of new arrangements by the end of Summer Term 2015, otherwise much of the new assessment and accountability package for secondary schools would have to be delayed until 2017.

Schools that have already taken advantage of the early opt in arrangements for Progress 8 would have some cause for complaint.

So if you have alternative solutions – that meet the manifesto commitment but would cause less disruption and difficulty for schools – I’m sure they would be delighted to hear them!

.

[Postscript, 12 June 2015:

On 11 June Minister of State for Schools Nick Gibb gave a speech at Policy Exchange entitled ‘Knowledge is power: The social justice case for an academic curriculum’.

The Policy Exchange website said:

‘The speech will set out the Government’s plans to build on previous reforms in the last Parliament, including the Conservative Manifesto commitment requiring all secondary school pupils to take GCSEs in EBacc subjects.’

On the morning of the speech, press officers moved to dampen expectations that it would contain much detail about this commitment.

The TES said:

‘Today the minister will say that details about the policy…are imminent’

While Schools Week preferred:

‘In a speech later today, Mr Gibb is expected to say the government will set out “in due course” further details of its plan…’.

The BBC report told us categorically that the provision ‘would not apply to pupils with special needs’.

All three sources confirmed that there would be consultation on how to implement the policy.

The speech itself offered hardly any new information:

‘In due course, we will also set out details of our expectation that secondary school pupils should take English Baccalaureate subjects at age 16. In doing so, we will listen closely to the views of teachers, headteachers, and parents on how best to implement this commitment. And we will ensure that schools have adequate lead in time to prepare for any major changes.

For some schools already leading the way, such as King Solomon Academy and Rushey Mead School, this change will pass by unnoticed. But for others, where only a small minority currently achieve the EBacc, there is no doubt that this will be a significant challenge. We will support these schools to raise standards, but make no apology for expecting every child to receive a high-quality core academic education.’

Incidentally, King Solomon Academy and Rushey Mead Academy were celebrated earlier in the speech:

‘King Solomon Academy, situated in the heart of a disadvantaged community in Paddington, is one of these schools. 67% of GCSE pupils at King Solomon Academy are eligible for the pupil premium, but despite this, 93% of pupils entered the EBacc, and 76% of pupils achieved it in 2014.

Rushey Mead School in Leicester is yet another example of an ‘outstanding’ school where they have high expectations for all their pupils. 33% of the school’s intake is eligible for the pupil premium, 72% are entered for the EBacc and 42% achieve it, well above the national average.’

.

.

One pointer is that the terminology in the Manifesto – ‘we will require…’ – has now been softened to ‘our expectation’. This suggests that the Government will not resort to compulsion.

The Q and A session following the speech is now available to listen to on Policy Exchange’s website.

When asked about the detailed proposals, Gibb said these would emerge ‘very soon’ from ‘somebody more important than me’.

It is unclear whether this is merely self-deprecation or an indication that they will be communicated by the Prime Minister (since the phrase ‘someone more important’ is often ministerial code for the PM).

.

.

This would help to explain why Gibb was left to give a speech bereft of the details most urgently awaited by his audience.

The Q and A helps to clear up a few issues.

- It appears that there will be a formal consultation process which, if launched before the end of term, would delay decisions until the autumn.

- The consultation will invite comments on the application of the policy to special schools (as opposed to special needs pupils), to UTCs and studio schools.

- The reference to an ‘adequate lead in time’ appears to be acknowledgment that the Workload Challenge agreement – requiring a year’s notice of significant changes – bites in this case.

The combined effect of the consultation period and the Workload Challenge provision may postpone implementation beyond September 2016. This could have implications for the introduction of Attainment/Progress 8.

No information was forthcoming about the Ofsted ‘limiting judgement’ or the nature and source of the support that would be provided to schools for which the policy is a ‘significant challenge’.

During the Q and A, Gibb made the point that it should apply equally to low attainers, citing some further data from his supporting brief about outcomes at King Solomon Academy.

I thought it would be wise to check the records of both named schools more closely in the 2014 Secondary Performance Tables.

- King Solomon Academy entered 89% of disadvantaged pupils for the EBacc compared with 100% of other pupils, a gap of 11 percentage points. Although 71% of low attainers were entered, only 43% were successful. Only 71% of middle attainers were successful.

- Rushey Mead School entered 63% of disadvantaged pupils for the EBacc compared with 76% of other pupils, a gap of 13 percentage points. Just 27% of low attainers were entered and only 4% were successful. Only 33% of middle attainers were successful.

Even though King Solomon leads the field in terms of EBacc entry and achievement by low attainers, it still has considerable scope for improvement. Rushey Mead has a mountain to climb. There are significant socio-economic gaps in the entry policy at both schools.

A strict interpretation of the manifesto commitment would by no means pass unnoticed in either of them.]

.

[Holding postscript 14 June: Press reports indicate that Secretary of State Morgan will announce details of the compulsory EBacc policy in a speech on 16 June to take place at King Solomon Academy.

The reports suggest that the policy will be introduced for all pupils starting their GCSEs in 2018.

Quite why Morgan wouldn’t allow Gibb to make this public on Thursday remains a mystery.

I will update this post to reflect what Morgan announces.]

.

[Postscript 16 June: A press release was issued in the morning and the text of a speech in the afternoon. The latter told us nothing new.

The press release provides a few further snippets of information:

- It says that:

‘Pupils starting secondary school this September must study the key English Baccalaureate (EBacc) subjects of English, maths, science, history or geography, and a language at GCSE.’

This is potentially ambiguous, but is clarified by a subsequent sentence:

‘The government’s intention is that pupils starting secondary school this September (year 7) will study the EBacc when they reach their GCSEs, with pupils taking exams in these subjects in 2020.’

It is not clear whether pupils will need to achieve a new-style level 5 in the specified subjects in order to achieve the EBacc.

- Despite this, Progress 8 will remain ‘the new headline performance measure’, confirming that Attainment/Progress 8 and the new EBacc requirement must necessarily co-exist.

- The footnotes add that

‘The government recognises the EBacc will not be appropriate for a small minority of pupils and so we will work to understand this and be clear with schools what we expect for this minority of pupils. The detail will be set out in the autumn and there will be a full public consultation on these proposals.’

It does not specify whether or not this small minority are the special needs pupils that the BBC reported would be exempt. There is an implication that there may be an alternative expectation in respect of them.

Further detail will not be available before next academic year.

I had assumed that the consultation might be launched immediately, running across the summer and into the first part of the autumn term. However, a Tweet from DfE during the afternoon made it clear that the consultation itself will also be delayed until next year.

.

This leaves most of the unanswered questions above still unanswered, for at least another three months. One imagines that a great deal of preparatory work will be necessary before a viable consultation document can be produced.

In the meantime, there are signs that professional opposition to the plan is gathering momentum.

On 17 June, SSAT reported the outcomes of a survey it had conducted amongst school leaders. The findings included:

‘Only 16% of respondents said that they would make the EBacc compulsory if that was a requirement for an Outstanding judgement from Ofsted.

70% of respondents would refuse to teach the EBacc for all, even if that meant a ceiling of Ofsted Good for their schools.

Over 44% of Outstanding schools would refuse to teach the EBacc for all, even if it meant losing their Outstanding status. A further 34% of Outstanding schools remain undecided. Only 1 in 5 Outstanding schools said that they would make the Ebacc compulsory for all.’

The consultation process is certain to be a difficult one, even though the press notice indicates the Government’s intention to ‘work with school leaders’ to ‘ensure all [sic] pupils get the chance to study these crucial subjects’.]

.

GP

May 2015

It explores the nature of excellence gaps, which I have

It explores the nature of excellence gaps, which I have