This post considers how England’s selective schools are addressing socio-economic disadvantage.

Another irrelevant Norwegian vista by Gifted Phoenix

It is intended as an evidence base against which to judge various political statements about the potential value of selective education as an engine of social mobility.

It does not deal with recent research reports about the historical record of grammar schools in this respect. These show that – contrary to received wisdom – selective education has had a very limited impact on social mobility.

Politicians of all parties would do well to acknowledge this, rather than attempting (as some do) to perpetuate the myth in defiance of the evidence.

This post concentrates instead on the current record of these schools, recent efforts to strengthen their capacity to support the Government’s gap closing strategy and prospects for the future.

It encourages advocates of increased selection to consider the wider question of how best to support high attainers from disadvantaged backgrounds.

The post is organised into four main sections:

- A summary of how the main political parties view selection at this point, some six months ahead of a General Election.

- A detailed profile of the socio-economic inclusiveness of grammar schools today, which draws heavily on published data but also includes findings from recent research.

- An evaluation of national efforts over the last year to reform selective schools’ admissions, testing and outreach in support of high-attaining disadvantaged learners.

- Comparison of the various policy options for closing excellence gaps between such learners and their more advantaged peers – and consideration of the role that reformed and/or increased selection might play in a more comprehensive strategy.

Since I know many readers prefer to read my lengthy posts selectively I have included page jumps from each of the bullet points above to the relevant sections below.

One more preliminary point.

This is the second time I have explored selection on this Blog, though my previous post, on fair access to grammar schools, appeared as far back as January 2011. This post updates some of the data in the earlier one.

One purpose of that earlier post was to draw attention to the parallels in the debates about fair access to grammar schools and to selective higher education.

I do not repeat those arguments here, although writing this has confirmed my opinion that they are closely related issues and that many of the strategies deployed at one level could be applied equally at the other.

So there remains scope to explore how appropriate equivalents of Offa, access agreements, bursaries and contexualised admissions might be applied to selective secondary admissions arrangements, alongside the reforms that are already on the table. I leave that thought hanging.

.

The Political Context

My last post on ‘The Politics of Setting’ explored how political debate surrounding within-school and between-school selection is becoming increasingly febrile as we approach the 2015 General Election.

The two have become inextricably linked because Prime Minister Cameron, in deciding not to accommodate calls on the right of his party to increase the number of selective schools, has called instead for ‘a grammar stream in every school’ and, latterly, for a wider – perhaps universal – commitment to setting.

In May 2007, Cameron wrote:

‘That’s what the grammar school row was about: moving the Conservative Party on from slogans such as ‘Bring back grammar schools’ so that we can offer serious policies for improving state education for everyone…

…Most critics seem to accept, when pressed, that as I have said, the prospect of more grammars is not practical politics.

Conservative governments in the past – and Conservative councils in the present – have both failed to carry out this policy because, ultimately, it is not what parents want….

…When I say I oppose nationwide selection by 11 between schools, that does not mean I oppose selection by academic ability altogether.

Quite the reverse. I am passionate about the importance of setting by ability within schools, so that we stretch the brightest kids and help those in danger of being left behind.’

With a Conservative Government this would be a motor of aspiration for the brightest kids from the poorest homes – effectively a ‘grammar stream’ in every subject in every school.

Setting would be a focus for Ofsted and a priority for all new academies.’

As ‘The Politics of Setting’ explained, this alternative aspiration to strengthen within-school selection has not yet materialised, although there are strong signs that it is still Cameron’s preferred way forward.

The Coalition has been clear that:

‘It is not the policy of the Government to establish new grammar schools in England’ (Hansard, 10 February 2014, Col. 427W).

but it has also:

- Removed barriers to the expansion of existing grammar schools through increases to planned admission numbers (PANs) within the Admissions Code.

- Introduced several new selective post-16 institutions through the free schools policy (though not as many as originally envisaged since the maths free schools project has made relatively little progress).

- Made efforts to reform the admissions procedures of existing selective secondary schools and

- Accepted in principle that these existing schools might also expand through annexes, or satellite schools. This is now a live issue since one decision is pending and a second proposal may be in the pipeline.

The Liberal Democrats have enthusiastically pursued at least the third of these policies, with Lib Dem education minister David Laws leading the Government’s efforts to push the grammar schools further and faster down this route.

In his June 2014 speech (of which much more below) Laws describes grammar schools as ‘a significant feature of the landscape in many local areas’ and ‘an established fact of our education system’.

But, as the Election approaches, the Lib Dems are increasingly distancing themselves from a pro-selective stance.

Clegg is reported to have said recently that he did not believe selective schools were the way forward:

‘The Conservatives have got this odd tendency to constantly want to turn the clock back.

Some of them seem to be hankering towards a kind of selective approach to education, which I don’t think works.

Non-selective schools stream and a lot of them stream quite forcefully, that’s all fine, but I think a segregated school system is not what this country needs.’

Leaving aside the odd endorsement of ‘forceful streaming’, this could even be interpreted as hostile to existing grammar schools.

Meanwhile, both frontrunners to replace Cameron as Tory leader have recently restated their pro-grammar school credentials:

- Constituency MP Teresa May has welcomed consideration of the satellite option in Maidenhead.

The right wing of the Tory party has long supported increased selection and will become increasingly vociferous as the Election approaches.

Conservative Voice – which describes itself as on the ‘center-Right of the party’ [sic] – will imminently launch a campaign calling for removal of the ban on new grammar schools to be included in the Conservative Election Manifesto.

They have already conducted a survey to inform the campaign, from which it is clear that they will be playing the social mobility card.

The Conservative right is acutely aware of the election threat posed by UKIP, which has already stated its policy that:

‘Existing schools will be allowed to apply to become grammar schools and select according to ability and aptitude. Selection ages will be flexible and determined by the school in consultation with the local authority.’

Its leader has spoken of ‘a grammar school in every town’ and media commentators have begun to suggest that the Tories will lose votes to UKIP on this issue.

Labour’s previous shadow education minister, Stephen Twigg, opposed admissions code reforms that made it easier for existing grammar schools to expand.

But the present incumbent has said very little on the subject.

A newspaper interview in January 2014 hints at a reforming policy:

‘Labour would not shut surviving grammar schools but Mr Hunt said their social mix should be questioned.

“If they are simply about merit why do we see the kind of demographics and class make-up within them?”’

But it seems that this has dropped off Labour’s agenda now that the Coalition has adopted it.

I could find no formal commitment from Labour to address the issue in government, even though that might provide some sort of palliative for those within the party who oppose selection in all its forms and have suggested that funding should be withdrawn from selective academies.

So the overall picture suggests that Labour and the Lib Dems are deliberately distancing themselves from any active policy on selection, presumably regarding it as a poisoned chalice. The Tories are conspicuously riven on the issue, while UKIP has stolen a march by occupying the ground which the Tory right would like to occupy.

As the Election approaches, the Conservatives face four broad choices. They can:

- Endorse the status quo under the Coalition, making any change of policy conditional on the outcome of a future leadership contest.

- Advocate more between-school selection. This might or might not stop short of permitting new selective 11-18 secondary schools. Any such policy needs to be distinct from UKIP’s.

- Advocate more within-school selection, as preferred by Cameron. This might adopt any position between encouragement and compulsion.

- Develop a more comprehensive support strategy for high attaining learners from disadvantaged backgrounds. This might include any or all of the above, but should also consider support targeted directly at disadvantaged students.

These options are discussed in the final part of the post.

The next section provides an assessment of the current state of selective school engagement with disadvantaged learners, as a precursor to describing how the reform programme is shaping up.

.

How well do grammar schools serve disadvantaged students?

.

The Grammar School Stock and the Size of the Selective Pupil Population

Government statistics show that, as of January 2014, there are 163 selective state-funded secondary schools in England.

This is one less than previously, following the merger of Chatham House Grammar School for Boys and Clarendon House Grammar School. These two Kent schools formed the Chatham and Clarendon Grammar School with effect from 1 September 2013.

At January 2014:

- 135 of these 163 schools (83%) are academy converters, leaving just 28 in local authority control. Twenty of the schools (12%) have a religious character.

- Some 5.1% of pupils in state-funded schools attend selective schools. (The percentage fluctuated between 4% and 5% over the last 20 years.) The percentage of learners under 16 attending selective schools is lower. Between 2007 and 2011 it was 3.9% to 4.0%.

- There are 162,630 pupils of all ages attending state-funded selective secondary schools, of which 135,365 (83.2%) attend academies and 27,265 (16.8%) attend LA maintained schools. This represents an increase of 1,000 compared with 2013. The annual intake is around 22,000.

The distribution of selective schools between regions and local authority areas is shown in Table 1 below.

The percentage of selective school pupils by region varies from 12.0% in the South East to zero in the North East, a grammar-free zone. The percentage of pupils attending selective schools by local authority area (counting only those with at least one selective school) varies from 45.1% in Trafford to 2.1% in Devon.

Some of the percentages at the upper end of this range seem to have increased significantly since May 2011, although the two sets of figures may not be exactly comparable.

For example, the proportion of Trafford pupils attending selective schools has increased by almost 5% (from 40.2% in 2011). In Torbay there has been an increase of over 4% (34.8% compared with 30.5%) and in Kent an increase of almost 4% (33.3% compared with 29.6%).

.

Table 1: The distribution of selective schools by region and local authority area and the percentage of pupils within each authority attending them (January 2014)

| Region |

Schools |

Pupils |

Percentage of all pupils |

| North East |

0 |

0 |

0 |

| North West |

19 |

20,240 |

4.9 |

| Cumbria |

1 |

833 |

2.8 |

| Lancashire |

4 |

4,424 |

6.6 |

| Liverpool |

1 |

988 |

3.3 |

| Trafford |

7 |

7,450 |

45.1 |

| Wirral |

6 |

6,547 |

30.5 |

| Yorkshire and Humberside |

6 |

6,055 |

1.9 |

| Calderdale |

2 |

2,217 |

14.2 |

| Kirklees |

1 |

1,383 |

5.5 |

| North Yorkshire |

3 |

2,454 |

6.5 |

| East Midlands |

15 |

12,700 |

4.5 |

| Lincolnshire |

15 |

12,699 |

26.9 |

| West Midlands |

19 |

15,865 |

4.5 |

| Birmingham |

8 |

7,350 |

10.4 |

| Stoke-on-Trent |

1 |

1,078 |

8.7 |

| Telford and Wrekin |

2 |

1,283 |

11.7 |

| Walsall |

2 |

1,423 |

7.0 |

| Warwickshire |

5 |

3,980 |

12.0 |

| Wolverhampton |

1 |

753 |

5.0 |

| East of England |

8 |

7,715 |

2.1 |

| Essex |

4 |

3,398 |

4.0 |

| Southend-on-Sea |

4 |

4,319 |

32.8 |

| London |

19 |

20,770 |

4.4 |

| Barnet |

3 |

2,643 |

11.6 |

| Bexley |

4 |

5,466 |

26.6 |

| Bromley |

2 |

1,997 |

9.0 |

| Enfield |

1 |

1,378 |

6.1 |

| Kingston upon Thames |

2 |

2,021 |

20.5 |

| Redbridge |

2 |

1,822 |

7.9 |

| Sutton |

5 |

5,445 |

30.7 |

| South East |

57 |

59,910 |

12.0 |

| Buckinghamshire |

13 |

15,288 |

42.2 |

| Kent |

32 |

33,059 |

33.3 |

| Medway |

6 |

6,031 |

32.2 |

| Reading |

2 |

1,632 |

24.1 |

| Slough |

4 |

3,899 |

37.4 |

| South West |

20 |

19,370 |

6.2 |

| Bournemouth |

2 |

2,245 |

23.3 |

| Devon |

1 |

822 |

2.1 |

| Gloucestershire |

7 |

6,196 |

16.2 |

| Plymouth |

3 |

2,780 |

16.3 |

| Poole |

2 |

2,442 |

26.8 |

| Torbay |

3 |

2,976 |

34.8 |

| Wiltshire |

2 |

1,928 |

6.6 |

| TOTAL |

163 |

162,630 |

5.1 |

.

Some authorities are deemed wholly selective but different definitions have been adopted.

One PQ reply suggests that 10 of the 36 local authority areas – Bexley, Buckinghamshire, Kent, Lincolnshire, Medway, Slough, Southend, Sutton, Torbay and Trafford – are deemed wholly selective because they feature in the Education (Grammar School Ballots) Regulations 1998.

Another authoritative source – the House of Commons Library – omits Bexley, Lincolnshire and Sutton from this list, presumably because they also contain comprehensive schools.

Of course many learners who attend grammar schools live in local authority areas other than those in which their schools are located. Many travel significant distances to attend.

A PQ reply from March 2012 states that some 76.6% of all those attending grammar schools live in the same local authority as their school, while 23.2% live outside. (The remainder are ‘unknowns’.)

These figures mask substantial variation between authorities. A recent study, for the Sutton Trust ‘Entry into Grammar Schools in England’ (Cribb et al, 2013) provides equivalent figures for each local authority from 2009-10 to 2011-12.

The percentage of within authority admissions reaches 38.5% in Trafford and 36% in Buckinghamshire but, at the other extreme, it can be as low as 1.7% in Devon and 2.2% in Cumbria.

The percentage of admissions from outside the authority can be as much as 75% (Reading) and 68% (Kingston) or, alternatively, as low as 4.5% in Gloucestershire and 6.8% in Kent.

.

Recent Trends in the Size and Distribution of the Disadvantaged Grammar School Pupil Population

Although this section of the post is intended to describe the ‘present state’, I wanted to illustrate how that compares with the relatively recent past.

I attached to my 2011 post a table showing how the proportion of FSM students attending grammar schools had changed annually since 1995. This is reproduced below, updated to reflect more recent data where it is available

A health warning is attached since the figures were derived from several different PQ replies and I cannot be sure that the assumptions underpinning each were identical. Where there are known methodological differences I have described these in the footnotes.

.

Table 2: Annual percentage FSM in all grammar schools and gap between that and percentage FSM in all secondary schools, 1995-2013

| Year |

PercentageFSM in GS |

Percentage FSMall schools |

Percentagepoint Gap |

| 1995 |

3.9 |

18.0 |

14.1 |

| 1996 |

3.8 |

18.3 |

14.5 |

| 1997 |

3.7 |

18.2 |

14.5 |

| 1998 |

3.4 |

17.5 |

14.1 |

| 1999 |

3.1 |

16.9 |

13.8 |

| 2000 |

2.8 |

16.5 |

13.7 |

| 2001 |

2.4 |

15.8 |

13.4 |

| 2002 |

2.2 |

14.9 |

12.7 |

| 2003 |

2.1 |

14.5 |

12.4 |

| 2004 |

2.2 |

14.3 |

12.1 |

| 2005 |

2.1 |

14.0 |

11.9 |

| 2006 |

2.2 |

14.6 |

12.4 |

| 2007 |

2.0 |

13.1 |

11.1 |

| 2008 |

1.9 |

12.8 |

10.9 |

| 2009 |

2.0 |

13.4 |

11.4 |

| 2010 |

|

15.4 |

|

| 2011 |

2.4 |

14.6 |

12.2 |

| 2012 |

|

14.8 |

|

| 2013 |

|

15.1 |

|

| 2014 |

|

14.6 |

|

(1) Prior to 2003 includes dually registered pupils and excludes boarding pupils; from 2003 onwards includes dually registered and boarding pupils.

(2) Before 2002 numbers of pupils eligible for free school meals were collected at school level. From 2002 onwards numbers have been derived from pupil level returns.

(3) 2008 and 2009 figures for all schools exclude academies

.

Between 1996 and 2005 the FSM rate in all schools fell annually, dropping by 4.3 percentage points over that period. The FSM rate in grammar schools also fell, by 1.7 percentage points. The percentage point gap between all schools and selective schools fell by 2.6 percentage points.

Both FSM rates reached their lowest point in 2008. At that point the FSM rate in grammar schools was half what it had been in 1996. Thereafter, the rate across all schools increased, but has been rather more volatile, with small swings in either direction.

One might expect the 2014 FSM rate across all grammar schools to be at or around its 2011 level of 2.4%.

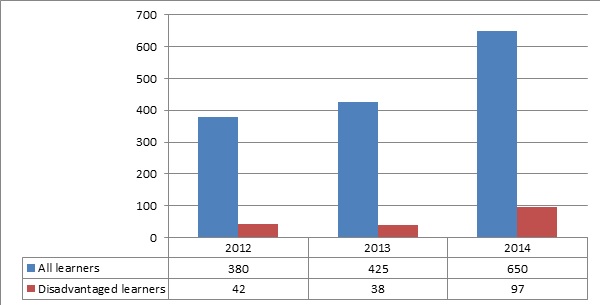

A more recent PQ reply revealed the total number of pupil premium recipients attending selective schools over the last three financial years:

- FY2011-12 – 3,013

- FY2012-13 – 6,184 (on extension to ‘ever 6’)

- FY2013-14 – 7,353

(Hansard 20 January 2014, Col. WA88)

This suggests a trend of increasing participation in the sector, though total numbers are still very low, averaging around 45 per school and slightly over six per year group.

.

Comparison with FSM rates in selective authorities

In 2012, a table deposited in the Commons Library (Dep 2012-0432) in response to a PQ provided the January 2011 FSM rates for selective schools and all state-funded secondary schools in each authority containing selective schools.

In this case, the FSM rates provided relate only to pupils aged 15 or under. The comparable national average rates are 2.7% for selective schools and 15.9% for all state-funded schools.

- Selective school FSM rates per authority vary between 6.0% in Birmingham and 0.6% in Wiltshire.

- Other authorities with particularly low FSM rates include Bromley (0.7%), Reading (0.8%) and Essex (0.9%).

- Authorities with relatively high FSM rates include Wirral (5.2%), Walsall (4.9) and Redbridge (4.8%).

- The authorities with the biggest gaps between FSM rates for selective schools and all schools are Birmingham, at 28.0 percentage points, Liverpool, at 23.8 percentage points, Enfield at 21.8 percentage points and Wolverhampton, at 21.7 percentage points.

- Conversely, Buckinghamshire has a gap of only 4.7 percentage points, since its FSM rate for all state-funded secondary schools is only 6.0%.

- Buckinghamshire’s overall FSM rate is more than four times the rate in its grammar schools, while in Birmingham the overall rate is almost six times the grammar school rate. On this measure, the disparity is greatest in metropolitan boroughs with significant areas of disadvantage.

.

Proportion of disadvantaged learners in each selective school

I attached to my 2011 post a table setting out the FSM rates (all pupils, regardless of age) for each selective school in January 2009.

This updated version sets out the January 2013 FSM and disadvantaged (ie ‘ever 6 FSM’) rates by school, drawn from the latest School Performance Tables. (Click on the screenshot below to download the Excel file.)

.

.

Key points include:

- The size of grammar schools varies considerably, with NORs ranging from 437 (Newport Girls’) to 1518 (Townley Girls’). The average NOR is slightly below 1000.

- 24 of the 163 schools (14.7%) have suppressed FSM percentages. Since the lowest published percentage is 1.1%, the impact of suppression is that all schools at or below 1.0% are affected. Since no school returns 0, we must assume that all contain a handful of FSM learners. It is notable that six of these schools are in Buckinghamshire, three in Gloucestershire and three in Essex. Both Bromley grammar schools also fall into this category.

- 67 selective schools (41.1%) have FSM rates of 2% or lower. The average FSM rate across all these schools is 3.25%.

- The highest recorded FSM rates are at Handsworth Grammar School (14.4%), King Edward VI Aston School (12.9%) and Stretford Grammar School (12%). These three are significant outliers – the next highest rate is 7.8%.

- As one would expect, there is a strong correlation between FSM rates and ‘ever 6’ rates. Most of the schools with the lowest ‘ever 6’ rates are those with SUPP FSM rates. Of the 26 schools returning ‘ever 6’ rates of 3.0% or lower, all but 7 fall into this category.

- The lowest ‘ever 6’ rate is the 0.6% returned by Sir William Borlase’s Grammar School in Buckinghamshire. On this evidence it is probably the most socio-economically selective grammar school in the country. Five of the ten schools with the lowest ‘ever 6’ rates are located in Buckinghamshire.

- A few schools have FSM and ‘ever 6’ rates that do not correlate strongly. The most pronounced is Ribston Hall in Gloucestershire which is SUPP for FSM yet has an ‘ever 6’ rate of 5.5%, not far short of the grammar school average which is some 6.6%. Clitheroe Royal Grammar School is another outlier, returning an ‘ever 6’ rate of 4.8%.

- The highest ‘ever 6’ rates are in Handsworth Grammar School (27.2%), Stretford Grammar School (24.3%) and King Edward VI Aston School (20.3%). These are the only three above 20%.

- In London there is a fairly broad range of socio-economic selectivity, from St Olave’s and St Saviour’s (Bromley) – which records an ‘ever 6’ rate of 2.5% – to Woodford County High School, Redbridge, where the ‘ever 6’ rate is 11%. As noted above, the FSM rates at the two Bromley schools are SUPP. The London school with the highest FSM rate is again Woodford County High, at 5%.

Another source throws further light on the schools with the lowest FSM rates. In October 2013, a PQ reply provided a table of the 50 state secondary schools in England with the lowest entitlement to FSM, alongside a second table of the 50 schools with the highest entitlement.

These are again January 2013 figures but on this occasion the rates are for pupils aged 15 or under and the only figures suppressed (denoted by ‘x’) are where no more than two pupils are FSM.

Sir William Borlase’s tops the list, being the only school in the country with a nil return (so the one or two FSM pupils who attend must be aged over 15 and may have been admitted directly to the sixth form).

The remainder of the ‘top ten’ includes eight selective schools and one comprehensive (Old Swinford Hospital School in Dudley). The eight grammar schools are:

- Cranbrook, Kent – x

- Adams’, Telford and Wrekin – x

- St Olave’s and St Saviour’s, Bromley – 0.5%

- Dr Challoner’s High Buckinghamshire – 0.5%

- Dr Challoner’s Grammar, Buckinghamshire – 0.6%

- Aylesbury Grammar, Buckinghamshire – 0.6%

- Newstead Wood, Bromley – 0.6%

- Pate’s, Gloucestershire – 0.6%

Comparing the data in my tables for 2009 and 2013 also throws up some interesting facts:

- Some schools have increased significantly in size – Burnham Grammar School (Buckinghamshire), Sir Thomas Rich’s (Gloucestershire), Highworth Grammar School for Girls (Kent), Simon Langton Grammar School for Boys (Kent), Kesteven and Grantham Girls’ School (Lincolnshire), Carre’s Grammar School (Lincolnshire) and St Joseph’s College (Stoke) have all increased their NORs by 100 or more.

- However, some other schools have shrunk significantly, notably The Skegness Grammar School in Lincolnshire (down 129), The Boston Grammar School in Lincolnshire (down 110), Fort Pitt Grammar School in Medway (down 132) and Slough Grammar School (down 175).

- While recognising that the figures may not be fully comparable, there have also been some significant changes in the proportions of FSM pupils on roll. Significant increases are evident at King Edward VI Aston (up 5.9 percentage points), Fort Pitt (up 5.1 percentage points) and Handsworth Grammar (up 4.7 percentage points).

- The only equally pronounced mover in the opposite direction is St Anselm’s College on The Wirral, where the FSM rate has more than halved, falling by 5.2 percentage points, from 9.8% to 4.6%.

Additional statistics were peppered throughout David Laws’ June 2014 speech.

He refers to a paper by DfE analysts which unfortunately has not been published:

- In 2013, 21 grammar schools had fewer than 1% of pupils eligible for FSM. Ninety-eight had fewer than 3% eligible and 161 had fewer than 10% eligible. This compares to a national average of 16.3% across England. (The basis for these figures is not supplied but they more or less agree with those above.)

- In Buckinghamshire in 2011, 14% of the year 7 cohort were eligible for the pupil premium, but only 4% of the cohort in Buckinghamshire grammar schools were eligible. In Lincolnshire the comparable percentages were 21% and 7% respectively.

.

Selectivity

Most commentary tends to regard the cadre of selective schools as very similar in character, leaving aside any religious affiliation and the fact that many are single sex establishments.

Although the fact is rarely discussed, some grammar schools are significantly more selective than others.

The 2013 Secondary Performance Tables show that only 10 grammar schools can claim that 100% of the cohort comprises high attainers. (These are defined on the basis of performance in statutory end of KS2 tests, in which they must record an APS of 30 or more across English, maths and science.)

At several schools – Clarendon House (Kent, now merged), Fort Pitt (Medway), Skegness (Lincolnshire), Dover Boys’ and Girls’ (Kent), Folkestone Girls’ (Kent), St Joseph’s (Stoke), Boston High (Lincolnshire) and the Harvey School (Kent) – the proportion of high attainers stands at 70% or below.

Many comprehensive schools comfortably exceed this, hence – when it comes to KS2 attainment – some comprehensives are more selective than some grammar schools.

Key variables determining a grammar school’s selectivity will include:

- The overall number of pupils in the area served by the school and/or the maximum geographical distance that pupils may travel to it.

- The number of pupils who take the entrance tests, including the proportion of pupils attending independent schools competing for admission.

- The number of competing selective schools and high-performing comprehensive schools, plus the proportion of learners who remain in or are ‘siphoned off’ into the independent sector.

- The number of places available at the school and the pass mark in the entrance tests.

I have been unable to locate any meaningful measure of the relative selectivity of grammar schools, yet this is bound to impact on the admission of disadvantaged learners.

An index of selectivity would improve efforts to compare more fairly the outcomes achieved by different grammar schools, including their records on access for disadvantaged learners.

.

Prior attainment data

In his June 2014 speech, Laws acknowledges that:

- ‘A key barrier is the low level of free school meal pupils achieving level 5, typically a proxy for pupils you admit’.

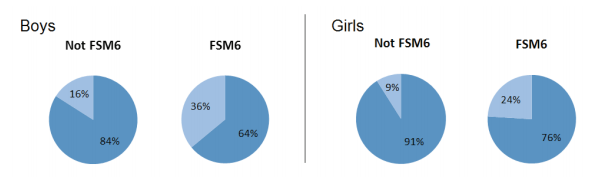

- However, in wholly selective areas fewer than 50% of FSM learners achieving Level 5 enter selective schools compared with two-thirds of non-FSM pupils:

‘We calculated it would require a shift of just 200 level 5 FSM pupils to go into grammar schools in wholly selective areas to remove this particular bias ‘

Alternative versions of this statement appear elsewhere, as we shall see below.

Using data from 2009/10 and 2011/12, the Sutton Trust study by Cribb et al explored whether advantaged and disadvantaged pupils with KS2 level 5 in both English and maths were equally likely to attend grammar schools.

They found that those not eligible for FSM are still more likely to attend. This applies regardless of whether the grammar school is located in a selective local authority, although the percentages and the gaps vary considerably.

- In selective authorities, some 66% of these high attaining non-FSM pupils went on to grammar schools compared with under 40% of FSM pupils, giving a gap of over 26 percentage points. (Note that the percentage for FSM is ten percentage points lower than the one quoted by Laws. I can find no reason for this disparity, unless the percentage has changed dramatically since 2012.)

- In isolated grammar schools outside London the gap is much smaller, at roughly 11 percentage points (18% non-FSM against 7% FSM).

- In London there is a similar 12 percentage point gap (15% non-FSM versus 3% FSM)

A similar pattern is detected on the basis of KS2 maths test fine points scores:

‘Two points are evident. First, for any given level of maths attainment, pupils who are eligible for FSM have a noticeably lower probability of attending a grammar school. Indeed, a non-FSM student with an average maths score has the same probability of entering a grammar school as an FSM pupil with a score 0.7 standard deviations above average. Second, the gap in probability of attendance between FSM and non-FSM pupils actually widens substantially: non-FSM pupils with test scores one standard deviation above average have a 55% likelihood of attending a grammar school in selective local authorities, whereas similar pupils who are eligible for FSM have only a 30% chance of attending a grammar school. This is suggestive that bright pupils from deprived families are not attending grammar schools as much as their attainment would suggest they might.’

This rather calls into question Laws’ initial statement that level 5 performance among FSM pupils is ‘a key barrier’ to admission.

The study also confirms that pupils attending primary schools with relatively high levels of deprivation are much less likely to progress to grammar schools.

On the other hand, some 13% of pupils nationally transfer into selective schools from non-state schools and schools outside England. The researchers are unable to distinguish clearly those from abroad and those from the independent sector, but note that they are typically wealthier than state school transfers.

This masks significant variation between local authority areas.

Almost 34% of such pupils transfer in to grammar schools in Essex, as do 24% in Bromley, 23% in Wiltshire and 22% in Bournemouth and Southend. At the other extreme, only 6% are incomers in Kirklees.

.

Headteacher perceptions

The Sutton Trust released a parallel research report from NATCEN reporting the outcomes of interviews with a small sample of three primary school and eight grammar school headteachers.

The researchers found that:

- Rightly or wrongly, many heads felt disadvantaged learners had relatively lower educational aspirations.

- Disadvantaged parents were sometimes perceived to know less about grammar schools and place less value on the benefits they might confer.

- Heads felt disadvantaged parents ‘often associated grammar schools with tradition, middle class values and elitism’. Parents felt their children ‘might struggle interacting with children from more affluent backgrounds’.

- Grammar school heads highlighted the role of primary schools but ‘this was difficult when primary schools disagreed with assessment based entry processes and selective education in general’.

- Heads felt grammar schools should provide more outreach and demonstrate their openness to everyone. It was suggested that, as grammar schools increasingly take in pupils from further away and/or from independent schools, this might further distance schools from their local communities.

- It was widely acknowledged that learners from more advantaged backgrounds were coached to pass the entrance exams. Some grammar heads regarded tutoring as ‘good examination preparation’; others recognised it as a barrier for disadvantaged learners.

- Although there are financial barriers to accessing grammar schools, including the cost of uniforms and school trips, grammar school heads claimed to deploy a variety of support strategies.

.

Overall

The preceding analysis is complex and difficult to synthesise into a few key messages, but here is my best effort.

The national figures show that, taken as a whole, the 163 grammar schools contain extremely low proportions of FSM-eligible and ‘ever 6’ learners.

National FSM rates across all grammar schools have fallen significantly over the past 20 years and, although the FSM gap between selective schools and all schools has narrowed a little, it is still very pronounced.

There is certainly a strong case for concerted action to reduce significantly the size of this gap and to strive towards parity.

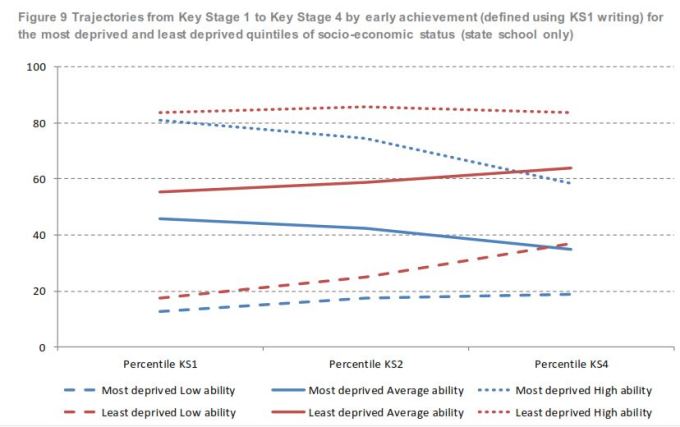

The disparity is no doubt partly attributable to lower rates of high attainment at KS2 amongst disadvantaged learners, but high attaining disadvantaged learners are themselves significantly under-represented. This is particularly true of wholly selective authorities but also applies nationally.

Although the sample is small, the evidence suggests that grammar school and primary head teachers share the perception that disadvantaged learners are further disadvantaged by the selective admissions process.

However, the cadre of grammar schools is a very broad church. The schools are very different and operate in markedly different contexts. Some are super-selective while others are less selective than some comprehensive schools.

A handful have relatively high levels of FSM and ‘ever-6’ admissions but a significant minority have almost negligible numbers of disadvantaged learners. Although contextual factors influence FSM and ‘ever 6’ rates significantly, there are still marked disparities which cannot be explained by such factors.

Each school faces a slightly different challenge.

Transparency and public understanding would be considerably improved by the publication of statistical information showing how grammar schools differ when assessed against a set of key indicators – and identifying clear improvement targets for each school.

There seem to me to be strong grounds for incorporating schools’ performance against such targets into Ofsted’s inspection regime.

.

Progress Towards Reform

.

The Sutton Trust Research

Although the Grammar School Heads’ Association (GSHA) argues that it has pursued reform internally for some years, a much wider-ranging initiative has developed over the last twelve months, kicked off by the publication of a tranche of research by the Sutton Trust in November 2013.

This included the two publications, by Cribb et al and NATCEN cited above, plus a third piece by Jesson.

There was also an overarching summary report ‘Poor Grammar: Entry into Grammar Schools for disadvantaged pupils in England’.

This made six recommendations which, taken together, cover the full spectrum of action required to strengthen the schools’ capacity to admit more disadvantaged learners:

- Review selection tests to ensure they are not a barrier to the admission of learners from disadvantaged backgrounds. The text remarks that:

‘Some grammar schools and local authorities are already trying to develop tests which are regularly changed, less susceptible to coaching, intelligence-based and not culturally biased.’

- Reduce the advantage obtained by those who can pay for private tuition by making available a minimum of ten hours of test preparation to all applicants on a free or subsidised basis.

- Improve grammar school outreach support, targeting learners from low and middle income backgrounds. This should include: assurances on access to transport and support with other costs; active encouragement for suitable Pupil Premium recipients to apply; using the media to dispel notions that grammar schools are exclusive and elitist; and deploying existing disadvantaged students as ambassadors.

- Using the flexibility within the Admissions Code (at this point available only to academies) to prioritise the admission of high achieving students who are entitled to the pupil premium. There is also a suggestion that schools might:

‘…consider giving preference to students from low or middle income households who reach a minimum threshold in the admission test’.

though it is not clear how this would comply with the Code.

- Develop primary-grammar school partnerships to provide transition support for disadvantaged students, enabling primary schools to provide stronger encouragement for applications and reassure parents.

- Develop partnerships with non-selective secondary schools:

‘…to ensure that high achieving students from low and middle income backgrounds have access to good local teachers in their areas.’

The Sutton Trust also made its own commitment to:

‘…look at ways that we can support innovation in improved testing, test preparation, outreach, admissions and collaboration.

We will also commission independent analysis of the impact of any such programmes to create an evidence base to enhance fair access to grammar schools.’

.

Reaction

Immediate reaction was predictably polarised. The GSHA was unhappy with the presentation of the report.

Its November 2013 Newsletter grumbles:

‘It is the way in which the research is presented by the Sutton Trust rather than any of research findings that give rise to concerns. Through a process of statistical machination the press release chose to lead on the claim that 6% of prep school pupils provide four times more grammar school pupils than the 16% of FSM eligible children. Inevitably, this led to headlines that the independent sector dominates admissions. The reality, of course is that 88% of all grammar school students come from state primary schools….

….Grammars select on ability and only 10% of FSM children reach level 5 at KS2 compared with a national average of 25%. The report, quite reasonably, uses level 5 as the indicator of grammar school potential. On the basis of this data the proportions of eligible FSM children in grammar schools is significantly greater than the overall FSM proportion in the top 500 comprehensives….

…In 2012 just over 500 FSM children entered grammar schools. For the success rate of L5 FSM to match that of other L5 would require 200 more FSM children a year to enter grammar schools. Just one more in each school would virtually close the gap….

….The recommendations of the report are not, as claimed, either new or radical. All are areas that had already been identified by GSHA as options to aid access and represent practices that are already adopted by schools. This work, however, is usually carefully presented to avoid promotion of a coaching culture.

It is unfortunate that the press briefing both contributed to reinforcing the false stereotyping of grammar schools and failed to signal initiatives taken by grammar schools.’

There is evidence here of retaliatory ‘statistical machination’, together with a rather defensive attitude that may not bode well for the future.

On the other hand HMCI Wilshaw was characteristically forthright in the expression of an almost diametrically opposite opinion.

In December 2013 he is reported to have said:

‘Grammar schools are stuffed full of middle-class kids. A tiny percentage are on free school meals: 3%. That is a nonsense.

Anyone who thinks grammar schools are going to increase social mobility needs to look at those figures. I don’t think they work. The fact of the matter is that there will be calls for a return to the grammar school system. Well, look what is happening at the moment. Northern Ireland has a selective system and they did worse than us in the [international comparison] table. The grammar schools might do well with 10% of the school population, but everyone else does really badly. What we have to do is make sure all schools do well in the areas in which they are located.’

.

The Laws Speech

Liberal Democrat Education Minister David Laws made clear the Government’s interest in reform with his June 2014 speech, already referenced above.

Early on in the speech he remarks that:

‘The debate about grammar schools seems to have been put in the political deep freeze – with no plans either to increase or reduce the number of what are extremely popular schools in their localities.’

With the benefit of hindsight, this seems rather ignorant of (or else disrespectful to) UKIP, which had nailed their colours to the mast just three weeks previously.

Laws acknowledges the challenge thrown down by Wilshaw, though without attribution:

‘Are you, as some would have it, “stuffed full of middle-class kids”?

Or are you opening up opportunities to all bright children regardless of their background, or can you do more?

Why is entry to grammar schools so often maligned?’

He says he wants to work with them ‘openly and constructively on social mobility’, to ‘consider what greater role they can play in breaking the cycles of disadvantage and closing the opportunity gap’, while accepting that the Government and the primary sector must also play their parts.

He suggests that the Government will do more to increase the supply of high attaining disadvantaged learners:

‘…a key barrier is the low level of free school meal pupils achieving level 5, typically a proxy for pupils you admit. So this is not just a challenge for grammar schools, but for the whole education system…

….My promise to you, alongside my challenge to you, is that this government will do everything in its power to make sure that more children from poorer backgrounds achieve their full potential.’

He lists the policies that:

‘Taken together, and over time…will start to shift the dial for poorer children – so that more and more reach level 5’

leading of course with the pupil premium.

He also proposes aspirational targets, though without any timescale attached:

‘My ambition is that all selective schools should aim for the same proportion of children on free school meals in their schools as in their local area.

This would mean an additional 3,500 free school meal pupils in selective schools every year, or an additional 35,000 pupils over 10 years.’

In relation to the flexibilities in the Admissions Code he adds:

‘I am pleased to be able to say that 32 grammar schools have implemented an admissions priority for pupils eligible for free school meals this year….

… We in the Department for Education will fully support any school that chooses to change its admissions criteria in this way – in fact, I want to see all grammar schools give preference to pupil premium pupils over the next few years.’

Similarly, on coaching and testing:

‘…I really welcome the association’s work to encourage a move to entry tests that are less susceptible to coaching, and I am heartened to hear that at least 40% of grammar schools are now moving to the introduction of coaching resistant tests.

Again, I hope that all grammar schools will soon do so, and it will be interesting to see the impact of this.’

And he adds:

‘I want all schools to build on the progress that is being made and seek to close the gap by increasing parental engagement, and stronger working with local primaries – with a focus on identifying potential.’

So he overtly endorses several of the recommendations proposed by the Sutton Trust seven months earlier.

A Sutton Trust press release:

‘…welcomed the commitment by Schools Minister David Laws, to widening access to grammar schools and making the issue a priority in government’.

This may be a little over-optimistic.

.

A Collaborative Project Takes Shape

Laws also mentions in his speech that:

‘The GSHA will be working with us, the Sutton Trust and the University of Durham to explore ways in which access to grammar schools by highly able deprived children might be improved by looking more closely at the testing process and what may be limiting the engagement of pupils with it.’

The associated release from the Sutton Trust uses the present tense:

‘The Trust is currently working with the King Edward VI Foundation, which runs five grammar schools in Birmingham, Durham University, the Grammar School Heads Association and the Department for Education to target and evaluate the most effective strategies to broaden access to grammar schools.

A range of initiatives being run by the Foundation, including test familiarisation sessions at community locations, visits from primary schools and support for numeracy and literacy teaching for gifted and talented children at local primary schools, will be evaluated by Durham University to understand and compare their impact. The resulting analysis will provide a template for other grammar schools to work with.’

We know that Laws had been discussing these issues with the grammar schools for some time.

When he appeared before the Education Select Committee in February 2014 he said:

‘We are trying, for example, to talk to grammar schools about giving young people fairer access opportunities into those schools. We are trying to allow them to use the pupil premium as a factor in their admissions policy. We are trying to encourage them to ensure that testing is fairer to young people and is not just coachable. ‘

The repetition of ‘trying’ might suggest some reluctance on the part of grammar school representatives to engage on these issues.

Yet press coverage suggested the discussions were ongoing. In May the GSHA Newsletter states that it had first met Laws to discuss admissions some eighteen months previously, so perhaps as early as November 2012.

It adds:

‘We are currently working on a research project with the DfE and the Sutton Trust to try to find out what practices help to reduce barriers to access for those parents and students from deprived backgrounds.’

A parallel report in another paper comments:

‘The grammar school heads have also gone into partnership with the education charity the Sutton Trust to support more able children from middle and lower income backgrounds applying to selective schools.

Other ideas being considered include putting on test familiarisation sessions for disadvantaged children – something they have missed out on in the past.’

While an entry on CEM’s website says:

‘Access Grammar:

This project seeks to look at ways access to grammar schools for highly able children from non-privileged backgrounds can be improved. The project will identify potential target cohorts in the study areas for a range of outreach interventions and will look to evaluate these activities. For this project, the CEM Research and Evaluation team are working in collaboration with the Sutton Trust, Grammar School Heads Association, King Edwards Foundation and the Department for Education.

Start date: January 2014

End date: January 2017.’

So we know that there is a five-way partnership engaged on a three year project, The various statements describing the project’s objectives are all slightly different, although there is a clear resemblance between them, the aims articulated by Laws and the recommendations set out by the Sutton Trust.

But I searched in vain for any more detailed specification, including key milestones, funding and intended outcomes. It is not clear whether the taxpayer is contributing through DfE funding, or whether the Sutton Trust and/or other partners are meeting the cost.

Given that we are almost a year into the programme, there is a strong case for this material to be made public.

.

Progress on Admissions Criteria

Of the issues mentioned in the Sutton Trust’s recommendations – tests and test preparation, admissions flexibility, outreach and partnership with primary and non-selective secondary schools – those at the front of the list have been most prominent (though there is also evidence that the King Edward’s Foundation is pursuing reform across a wider front).

The GSHA’s May 2014 newsletter is less grumpy than its predecessor, but still strikes a rather defensive note.

It uses a now familiar statistic, but in a slightly different fashion:

‘The actual number of students with Level 5s in their SATs who either choose not to apply to a grammar school or who apply but do not receive a place is reckoned by GSHA and the DfE to be two hundred students a year; not the very large number that the percentages originally suggested.’

This is the third time we have encountered this particular assertion, but each time it has been articulated differently. Which of the three statements is correct?

The GSHA is also keen to emphasise that progress is being made independently through its own good offices. On admissions reform, the article says:

‘A significant number of schools 38 have either adopted an FSM priority or consulted about doing so in the last admissions round. A further 59 are considering doing so in the next admissions round.’

The GHSA was also quoted in the TES, to the effect that 30 grammar schools had already been given permission by DfE to change their admissions policies and would so with effect from September 2015, while a further five or six had already introduced the reform.

A November 2014 PQ reply updates the figures above, saying that 32 grammar schools have already prioritised disadvantaged learners in their admissions arrangements and a further 65 ‘intend to consult on doing so’.

That leaves 66 (40%) which are not giving this active consideration.

The Chief Executive of the GSHA commented:

‘“You won’t notice a dramatic change in schools themselves because the numbers are quite small…This is reaching out at the margins in a way that won’t deprive other people of a place. The real need is to raise the standard among free school meals pupils at Key Stage 1 and Key Stage 2, that’s the key issue.

“What we are looking at in the meantime is what we can do to help these free school meals pupils who want to come to grammar school.”

Mr Sindall said that many of the country’s 164 grammar schools would not change their policies because competition for places was less fierce and it would be unnecessary. Many schools were also increasing outreach programmes and some were running eleven-plus familiarisation sessions to help prepare poorer children for the test, he added.’

There is evidence here of a desire to play down the impact of such changes, to suggest that the supply of disadvantaged high achievers is too small to do otherwise.

The data analysis above suggests that almost all selective schools need to address the issue.

Between them, the various press reports mention admissions changes at several schools, including Rugby High, South Wilts, ‘a series of Buckinghamshire grammars including Sir William Borlase’s, Dr Challoner’s and Aylesbury Grammar’, as well as the King Edward’s Foundation Schools in Birmingham.

I checked how these changes have been embodied in some of these schools’ admissions policies.

The reports indicated that Rugby was:

‘…going even further by reserving a fixed number of places for FSM-eligible children, so potentially accepting pupils with lower entrance exam scores than other applicants.’

Rugby’s admissions arrangements for 2015 do indeed include as a second overall admissions priority, immediately following children in care:

‘Up to 10 places for children living within the priority circle for children in receipt of Free School Meals whose scores are between one and ten marks below the qualifying score for entry to the school.’

South Wilts included FSM as an oversubscription criterion in its 2014 admission arrangements, replacing it with pupil premium eligibility in 2015. However, in both cases it is placed third after children in care and those living in the school’s designated [catchment] area.

Sir William Borlase’s goes one better, in that its 2015 admissions policy places children eligible for free school meals immediately after ‘children in care’ and before ‘children living in the catchment area of the school’, though again only in the oversubscription criteria.

The King Edward’s Foundation is pursuing a similar route to Rugby’s. It announced its intention to reform admissions to its five Birmingham grammar schools in April 2014:

‘The Government wishes to improve the social mobility of children in the UK and has urged selective schools to consider how their admission policies could be changed to achieve this. The King Edward VI Grammar Schools have applied to the Department for Education which can allow them to give preference in their policies, to children who are on free school meals, or have been at any point in the last six years…

… In addition the grammar schools will be offering familiarisation sessions which will introduce children from less privileged backgrounds to the idea of attending a grammar school and will encourage them to take the 11+.

All of the Grammar Schools have set themselves a target of a 20% intake of children on free school meals (Aston has already achieved this and has a target of 25%). The expansion of the grammar schools which was announced earlier this year means that these additional children will simply fill the additional space.’

According to the 2013 Performance Tables, the FSM rates at each of these schools in January 2013 were:

- Aston – 12.9%

- Camp Hill Boys – 3.6%

- Camp Hill Girls – 5.3%

- Five Ways – 2.6%

- Handsworth Girls – 6.3%

There must have been a major improvement at Aston for the September 2013 admissions round. As for the other four schools, they must increase their FSM admissions by a factor of between 4 and 8 to reach this target.

I wonder whether the targets are actually for ‘ever 6’ admissions?

In the event, the Foundation’s applications encountered some difficulties. In July the Admissions Adjudicator was obliged to reject them.

A parent had objected on the grounds that:

‘…it is necessary to request financial information from parents to achieve this priority which is contrary to paragraph 1.9(f) of the School Admissions Code.

… The objector further feels that it is unclear, unfair and unreasonable to use the pupil premium to differentiate between applications when the school is oversubscribed.’

The Adjudicator found in favour of the parent on the technical grounds that, although the schools had applied for variations of their funding agreements to permit this change, they had only done so retrospectively.

However, in each case:

‘The school is now entitled to give priority to girls eligible for the pupil premium as the funding agreement has been amended.’

By August the Foundation was able to state that the issue had been resolved:

‘Children applying for a place at any of the King Edward VI Grammar Schools must now achieve a minimum “qualifying score” in the test to be eligible for entry.

Any Looked After Child or previously Looked After Child (a child who is or has been in the care of the Local Authority) who achieves the “qualifying score” will be given priority for admission for up to 20% of the available places (25% at Aston).

Children eligible for Pupil Premium (those who have been registered for Free School meals at any point in the 6 years prior to the closing date for registration, 11 July 2014) who achieve the “qualifying score” will also be given priority for admission.

After this allocation, children not eligible for the Pupil Premium but who achieve the “qualifying score” will be admitted by rank order of scores until all places are filled.’

The Foundation has published an interesting FAQ on the new arrangements:

‘Q5. Will this mean that if you are poor you won’t have to score as high in the 11+ admission tests?

A. That is essentially correct – up to 20% of places (25% at Aston) are set aside for pupil premium children who achieve “a qualifying score”. This qualifying score will be set before the test in September after we have reviewed data in order to ensure that children who achieve the score can flourish in our schools.

Q6. Why don’t you want the cleverest children at your school anymore?

A. We want our schools to represent the City of Birmingham and the diverse backgrounds that our children might come from. We believe that there are clever children out there who just don’t have the same opportunity to succeed as those from more privileged backgrounds and we want to try to do something about that.’

It acknowledges the magnitude of the challenge ahead:

‘John Collins, Secretary to the Governors of the charity The Schools of King Edward VI in Birmingham said “This is a hugely challenging target which we do not expect to achieve in the first few years of the initiative, as currently there are relatively few free school meal pupils who apply to take the test. These low numbers are something we are trying to address with our “familiarisation” programme which seeks to encourage bright children from less privileged backgrounds to take the test.”’

Also in July the Government opened up the same possibility for grammar schools that are not academies by consulting on amendments to the Admissions Code to permit this.

In October this was confirmed in the Government’s response to the consultation which stressed it was being introduced as an option rather than a universal requirement.

.

Progress on 11+ Test Reform

The new-style 11-plus tests developed by CEM have not had a universally positive reception. Much of the attention has been focused on their adoption by Buckinghamshire grammar schools.

The GSHA’s May 2014 newsletter notes that ‘some schools in the Midlands’ have been using CEM tests for five years. From 2015, 40% of grammar schools will be using these tests, which are:

‘…designed to be immune to the influence of coaching’

adding:

‘The analysis of data from Buckinghamshire (a wholly selective area which has recently switched to the CEM Centre tests) will provide us in time with valuable hard data on the large scale impact of the change over time.’

Back in February 2014 an Observer article had already cited positive feedback from Buckinghamshire:

‘Last autumn, a handful of education authorities in England introduced an exam designed to test a wider range of abilities – ones that are already being taught in primary schools, rather than skills that can be mastered through home tutoring – to make the selection system fairer.

Provisional results indicate that a more diverse selection of pupils passed this test, and headteachers say they feel the change has made a difference.

Ros Rochefort, headteacher at Bledlow Ridge primary school in Buckinghamshire…said that this year, for the first time in her career, the test has delivered a fair result. “All the kids who got through were expected to pass and, as usual, there are a couple of appeals coming through. All our very able children were selected….

…. Philip Wayne, headteacher at Chesham grammar school and chairman of the Bucks Grammar School Heads Association, has welcomed the changes and says he is “very confident” that the new test will avoid the current situation, in which many pupils who won places at his school with the help of intensive tutoring struggle to keep up with lessons once they arrive.’

However, there were contemporary reports that the 2013 tests led to a 6% fall (110 fewer pupils) in the proportion of places awarded to children from in-county state primary schools, even though 300 more pupils applied.

In September this was further developed in a Guardian story:

‘According to the data, a child from a Buckinghamshire private school is now more than three and a half times more likely to pass the 11-plus than a child from one of its state primaries….

…FOI requests to the eight secondary schools in Wycombe, which includes some of the most deprived and diverse wards in the county, suggest that children on free school meals and of Pakistani heritage have been less successful this year. ‘

A local pressure group Local Equal and Excellent has been trying to gather and analyse the data from the initial rounds of testing in 2013 and 2014 (ie for admission in 2014 and 2015).

Their most recent analysis complains at refusals to publish the full test data and contains an analysis based on the limited material that has been released.

In November 2014, the matter was discussed at Buckinghamshire’s Education, Skills and Children’s Services Select Committee.

The ‘results and analysis’ paper prepared by Buckinghamshire’s grammar school headteachers contains many words and far too few numbers.

The section on ‘Closing the gap’ says:

‘One local group has claimed that children from poorer backgrounds and BME have ‘done worse’ in the new Secondary Transfer Test. It is not specified what ‘worse’ means; however it is not reliable to make statements about trends and patterns for specific groups from a single year’s data and as stated above the data that has been used to make such claims is a small subset of the total and unrepresentative. To substantiate such claims a detailed analysis of additional information such as the current attainment of the children concerned would be needed. We are currently considering how a longitudinal study might be achieved.’

This is overly defensive and insufficiently transparent.

There is some disagreement about whether or not the new test is less amenable to coaching.

The ‘results and analysis’ paper says:

‘There is no such thing as a ‘tutor proof’ test. However, the new tests are less susceptible to the impact of specific test tutoring because they are aligned to the National Curriculum which all children study. Additionally, the questions in the new test are less predictable than in the previous test because they cover a wider range of topics and there is a broader range of question types – points acknowledged and welcomed by primary headteachers’.

Conversely, the pressure group says:

‘The new 11-plus, devised by the Centre for Evaluation and Monitoring (CEM) at Durham University, is supposed to rely less heavily on verbal reasoning and be more closely allied to the primary curriculum. Practice papers for the CEM test are supposed to be less readily available…

But… the fact that it is modelled on what can be taught in schools means the CEM test is more amenable to coaching… if children can’t be taught to get better in maths, why are we teaching it in schools? Practice will make anyone better and I see no sign that tuition has tailed off at all.’

Elsewhere there is evidence that 11+ testing is not immune to financial pressures. North Yorkshire is presently consulting on a plan to scale back from a familiarisation test and two sets of two full tests, with the best results taken forward.

Instead there would be a single set of tests taken by all candidates on the same day at a single venue, plus sample booklets in place of the familiarisation test. A system of reviews, enabling parents to provide supporting evidence to explain under-performance, would also be discontinued.

The reason is explicit:

‘The cost of administering an overly bureaucratic system of testing is no longer sustainable in the light of very significant cuts in public expenditure.’

Even though the draft impact assessment says that the Council will consider applications for support with transport from rural areas and for those with low incomes, there is some unacknowledged risk that the new arrangements will be detrimental to efforts to increase the proportion of disadvantaged learners admitted to these schools.

.

How Best to Close Excellence Gaps

.

What to do with the status quo

The next Government will inherit:

- The Access Grammar reform project, outlined above, which is making some progress in the right direction, but needs closer scrutiny and probably more central direction. There is an obvious tension between Laws’ aspiration that all grammar schools should ‘give preference to pupil premium pupils over the next few years’ and the GSHA position, which is that many schools do not need to change their policies. It will be important that the changes to admissions arrangements for the 163 schools are catalogued and their impact on admissions monitored and made public, so that we can see at a glance which schools are leading the pack and which are laggards. A published progress report against the Sutton Trust’s six recommendations would help to establish future priorities. Greater transparency about the project itself is also highly desirable.

- A small cadre of selective 16-19 free schools. It will need to articulate its position on academic selection at 16+ and might need to take action to ensure a level playing field with existing sixth form colleges. It might consider raising expectations of both new and existing institutions in respect of the admission of disadvantaged learners, so securing consistency between 11+ selection and 16+ selection.

- Flexibility within the Admissions Code for all grammar schools – academies and LA-maintained alike – to prioritise the admission of disadvantaged learners. It may need to consider whether it should move further towards compulsion in respect of grammar schools, particularly if the GSHA maintains its position that many do not need to broaden their intake in this fashion.

- Flexibility for all grammar schools to increase Planned Admission Numbers and, potentially, to submit proposals for the establishment of Satellite institutions. The approval of such proposals rests with the local authority in the case of a maintained school but with the Secretary of State for Education in respect of academies. An incoming government may need to consider what limits and conditions should be imposed on such expansion, including requirements relating to the admission of disadvantaged learners.

It may be helpful to clarify the position on satellites. The Coalition Government has confirmed that they can be established:

‘It is possible for an existing maintained grammar school or academy with selective arrangements to expand the number of places they offer, including by extending on to another site…There are, however, limitations on that sort of expansion, meaning it could only be a continuation of the existing school. The school admissions code is written from a presumption that those schools with a split site are a single school’ (Hansard, 16 February 2012, Col. 184W).

In December 2013, a proposal to establish a grammar school annexe in Sevenoaks, Kent was rejected by the Secretary of State on the grounds that it would constitute a new school:

‘Mr Gove’s legal ruling hinged on the issue of a girls’ grammar school being the sponsor of a Sevenoaks annexe for both girls and boys. The planned entry of Sevenoaks boys to the annexe lead Mr Gove to rule that the annexe’s proposed admissions policy was sufficiently different to the sponsor school’s girls-only admissions policy to constitute a wholly new grammar school.’

But a revised proposal was submitted in November 2014 for a girls’ only annexe. Moreover, the local authority has committed to exploring whether another satellite could be established in Maidenhead, acknowledging that this would require the co-operation of an existing grammar school.

The timing of the decision on the revised Sevenoaks proposal ensures that selection will remain a live issue as we approach the General Election

.

Further options to promote between-school selection

There are several options for strengthening a pro-selection policy further that would not require the removal of statutory constraints on opening new 11-18 grammar schools, or permitting existing schools to change their character to permit selection.

For example:

- Pursuing the Wilshavian notion of organising schools into geographical clusters, some with academic and others with vocational specialisms, and enabling learners to switch between them at 14+. In many areas these clusters will incorporate at least one grammar school; in others the ‘academic’ role would be undertaken by high-performing comprehensive schools with strong sixth forms. The practical difficulties associated with implementing this strategy ought not to be underplayed, however. For example, how much spare capacity would the system need to carry in order to respond to annual fluctuations in demand? How likely is it that students would wish to leave their grammar schools at 14 and what tests would incomers be expected to pass? Would the system also be able to accommodate those who still wished to change institution at age 16?

- Vigorously expanding the cadre of post-16 selective free schools. There is presumably a largely unspent budget for up to twelve 16-19 maths free schools, though it will be vulnerable to cuts. It would be relatively straightforward to develop more, extending into other curricular specialisms and removing the obligatory university sponsorship requirement. Expansion could be focused on clones of the London Academy of Excellence and the Harris Westminster Sixth Form. But there should be standard minimum requirements for the admission of disadvantaged learners. A national network might be created which could help to drive improvements in neighbouring primary and secondary schools.

- Permit successful selective post-16 institutions to admit high-attaining disadvantaged students at age 14, to an academic pathway, as a parallel initiative to that which enables successful colleges to take in 14 year-olds wishing to study vocational qualifications. It may be that the existing scheme already permits this, since the curriculum requirements do not seem to specify a vocational pathway.

UKIP’s policy, as presently articulated, is merely enabling: few existing schools are likely to want to change their character in this fashion.

One assumes that Tory advocates would be satisfied with legislation permitting the establishment of new free schools that select at age 11 or age 14. It seems unlikely that anyone will push for the nuclear option of ‘a grammar school in every town’… but Conservative Voice will imminently reveal their hand.

.

Further options to promote within-school selection

If the political preference is to pursue within-school provision as an alternative to between-school selection there are also several possibilities including:

- Encouraging the development of more bilateral schools with parallel grammar and selective streams and/or fast-track grammar streams within standard comprehensive schools.

- Requiring, incentivising or promoting more setting in secondary schools, potentially prioritising the core subjects.

- Developing a wider understanding of more radical and innovative grouping practices, such as vertical and cluster grouping, and trialling the impact of these through the EEF.

It would of course be important to design such interventions to benefit all students, but especially disadvantaged high attainers.

The Government might achieve the necessary leverage through a ‘presumption’ built into Ofsted’s inspection guidance (schools are presumed to favour the specified approach unless they can demonstrate that an alternative leads consistently to higher pupil outcomes) or through a ‘flexible framework’ quality standard.

.

A national student support scheme

The most efficient method of supporting attainment and social mobility amongst disadvantaged high attainers is through a national scheme that helps them directly, rather than targeting the schools and colleges that they attend.

This need not be a structured national programme, centrally delivered by a single provider. It could operate within a framework that brings greater coherence to the existing market and actively promotes the introduction of new suppliers to fill gaps in coverage and/or compete on quality. A ‘managed market’ if you will.

The essential elements would include:

- This supply-side framework, covering the full range of disadvantaged students’ learning and development needs, within which all suppliers – universities, third sector, commercial, schools-based – would position their services (or they would be excluded from the scheme).

- A commitment on the part of all state-funded schools and colleges to implement the scheme with their disadvantaged high attainers (the qualifying criterion might be FSM or ‘ever 6’) – and to ensure continuity and progression when and if these students change institution, especially at 16+.

- A coherent learning and development programme for each eligible student throughout Years 7-13. Provision in KS3 might be open access and light touch, designed principally to identify those willing and able to pursue the programme into KS4 and KS5. Provision in these latter stages would be tailored to individuals’ needs and continuation would be dependent on progress against challenging but realistic personal targets, including specified GCSE grades.

- Schools and colleges would act as facilitators and guides, conducting periodic reviews of students’ needs; helping them to identify suitable services from the framework; ensuring that their overall learning programmes – the in-school/college provision together with the services secured from the framework – constitute a coherent learning experience; helping them to maintain learning profiles detailing their progress and achievement.

- Each learner would have a personal budget to meet costs attached to delivering his learning programme, especially costs attached to services provided through the framework. This would be paid through an endowment fund, refreshed by an annual £50m topslice from the pupil premium budget (analogous to that for literacy and numeracy catch-up) and a matching topslice from universities’ outreach budgets for fair access.

- Universities would be strongly encouraged to make unconditional offers on the basis of high quality learning profiles, submitted by students as part of their admissions process.

- There would be annual national targets for improving the GCSE and A level attainment of students participating in the scheme and for admission to – and graduation from – selective universities. This would include challenging but realistic targets for improving FSM admission to Oxbridge.

.

Conclusion

The current political debate is overly fixated on aspects of the wider problem, rather than considering the issue in the round.

I have set out above the far wider range of options that should be under consideration. These are not necessarily mutually exclusive.

If I were advising any political party inclined to take this seriously, I would recommend four essential components:

- An enhanced strategy to ensure that all existing selective schools (including 16+ institutions) take in a larger proportion of high-attaining disadvantaged learners. Approval for expansion and any new schools would be conditional on meeting specified fair access targets.

- Development of the cadre of 163 grammar schools into a national network, with direct responsibility for leading national efforts to increase the supply of high-attaining disadvantaged learners emerging from primary schools. Selective independent schools might also join the network, to fill gaps in the coverage and fulfil partnership expectations.